Chapter 10: Rivaling Tayloe

The Doctor Examined, or Why William Thornton Did Not Design the Octagon House or the Capitol

Chapter 10: Rivaling Tayloe

|

| Mrs. Thornton by Stuart 1804 |

The General died at Mount Vernon on December 14, 1799. Thornton came with the Laws a day later. Years later, he would write that he offered to restore the frozen corpse to life, but was "not seconded." However, the corpse was not frozen. According to Jefferson's thermometer in the Virginia foothills, afternoon temperatures were around 40F. Tobias Lear reported the events surrounding the death and burial in meticulous detail. He didn't mention a frozen corpse or Thornton's offer. He did note that the attending physician and Dr. Thornton vetoed his suggestion that the burial be delayed so more family could attend the funeral. The doctors said the inflammatory nature of the General's fatal disease made the corpse susceptible to decay and had to be buried as soon as the General's wishes allowed. On his death bed, he had requested that he not be entombed for two days on the odd chance that he wasn't really dead.(1)

He was thinking of the family tomb nearby. Thornton and many others thought the General's tomb should be in the Capitol. Because of that, the General's death could have been a godsend for Thornton in that he hoped it would hasten the completion of the Capitol. The House of Representatives resolved that the General's tomb should be there. He wrote to the author of the resolves, General John Marshall, whom he had never met, congratulating the House for its resolution and noting that putting the body in the center of "that national temple... will be a very great inducement to the completion of the whole building, which has been thought by some contracted minds, unacquainted with grand works, to be upon too great a scale." A month later Marshall acknowledged receiving the letter but didn't react to Thornton's vision. Even Mrs. Thornton seemed unexcited by her husband's letter. In her diary, she merely noted that he urged that the body of Mrs. Washington also be placed in the tomb.(2)

In the diary in which she described activities for every day of the year 1800, she principally recorded what her husband did, but rarely provided background that would illuminate exactly what he did and why. Nor did she assess the motives of others. That lack of context has made it easier for historians to jump to conclusions.

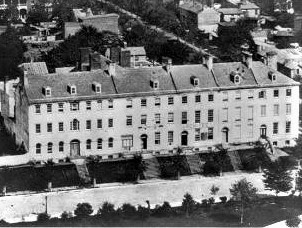

For example, on January 3, Mrs. Thornton noted that her husband received a request from the executors of the General's estate "requesting information respecting the General's two houses." She added: "The money paid to the undertaker of them having all gone through my husband's hands, he having superintended them as a friend." In her history of Capitol Hill, Pamela Scott claims that Thornton "suggested alterations to Washington's design for his double houses and oversaw their construction." One of the suggested alterations was the never built party wall. The other violated a building regulation. Other than his April 1799 instructions to workers about the door sill, the only evidence that Thornton inspected the house is Mrs. Thornton's diary. To better support her claim that Thornton oversaw construction, Scott quotes the only observation Mrs. Thornton made when they visited the two house on January 4: "...one of which is nearly finished - they are divided to let as one or two houses."

That is information the overseer of construction might gather, but her diary entry on January 21 makes her husband's role clear. He learned that the executors wouldn't meet until then. So, "very early in the morning," Thornton sent his slave Joe Key to get the information requested from the builder Blagden which amounted to "his account of the money he had received...." The houses had not been finished. She never mentioned Blagden again or his assistant Lenthall. The only other evidence for Thornton's overseeing construction is in the letters the General wrote to him between October and December 7. Rather than a novice taking the advice of the man who a century later would be proclaimed the greatest American architect of the 18th century, the General schooled Thornton in building techniques. He reminded him to get the contractors to paint sashes before installing them, instructed him on the proper mixture of sand in the paint for the walls and lectured him on plaster of Paris. After that last lesson, Thornton referred Washington to a pamphlet on the subject written by a Pennsylvania judge. While president, the General had asked the judge to do the research and write the pamphlet. Most of the letters Thornton wrote to the General during that period have gone missing.

On January 7, Mrs. Thornton noted: "....After dinner we walked to take a look at Mr. Tayloe's house which begins to make a handsome appearance." C. M. Harris counts that entry and seven other less informative entries in which she mentioned walking by the house, as evidence that Thornton kept tabs on the house he designed. Why else would they take a walk to see it?(3)

However, as is often the case in diaries, the sentence before describing her walk relates to the walk: "The Commissioners received a letter from the Secy of the Navy (Mr. Stoddert) mentioning that the President's time being expired in the house he now occupies that he intends removing his furniture here in June."(4)

|

| The Octagon in 1807 |

In that letter, Stoddert also told the board that the president insisted on moving

into the President's house. He would not be told where he might

have to stay and

jumped to the conclusion that the commissioners wanted to put him into

George Washington's Capitol Hill houses. Commissioner White was not in the city on January 7. Evidently, he had not told his

colleagues what he had written to the president. Commissioner Scott had

not signed the November letter and assumed that in his private letter, White had asked the president

to choose a house to be rented. Scott dashed a letter off to Stoddert

disavowing the very idea of not using the President’s house. Thornton

also signed that letter.

Scott likely got Thornton to reveal what houses he and White had in mind. Scott had sold the lot to Tayloe and likely remained a friend. Andrew McDonald, the master carpenter then working on the Octagon, had worked on Scott's mansion, Rock Hill, situated just north of the city. Scott likely knew that Tayloe's house would not be in a state to receive the president's furniture in June 1800. So, he likely challenged Thornton to see for himself what state the house was in. He wasn't taking a walk to check on a house he had designed.(5)

On the 12th, a Sunday, Mrs. Thornton described their visit to Capitol Hill with Thomas and Patsy Peter. They went into the General's houses. The Peters were not executors and not singled out in the will with any special gift. Patsy's brother, George Washington Parke Custis inherited Square 21 on Peter's Hill. The houses weren't mentioned in the will. Then they went to Law's house, and Mrs. Thornton didn't mention that who designed it. They found Law's house locked. So, "...we entered by the kitchen window and went all over it— It is a very pleasant roomy house but the Oval drawing room is spoiled by the lowness of the Ceiling, and two Niches, which destroy the shape of the Room.— Mr and Mrs Peter dined with us and returned home early in the afternoon some of her Children not being well."(6) Her only other mention of the house came on February 17: "Mr. Law is fixed in his new house and is quite pleased with it...."

Harris opines that "Thornton's role... is partially but substantially documented by his wife's diary for 1800." Certainly, that Thornton climbed through the kitchen window to get inside suggests he had some authority, though his friendship with Law and his touring with Mrs. Law's sister might have given him sufficient license to do that. Pamela Scott puts it this way: "It was designed by William Thornton, and was 'a very pleasant roomy house' according to Anna Maria Thornton."(7)

But how does one account for Mrs. Thornton's criticism of the oval drawing room's low ceiling? Her husband likely informed her criticism of the room. In 1797, Thornton had written to Dr. Fothergill about the Capitol's as yet unbuilt grand oval vestibule that was 114 feet in diameter and "full of broad prominent lights and broad deep shadows." His elevation's highlight was a stately dome. He had been struck by Lovering's ingenious design, but his oval rooms were 32 and 30 feet on their longer axis and 12 and 10 feet high. Fitting oval rooms into a five story townhouse was alien to Thornton's sensibilities.(8)However, while his merely looking at houses cannot prove that he designed them, there is no doubt that in early 1800, Thornton had an itch for drawing plans. On the afternoon of Saturday January 4, after seeing the General's houses, he took his wife and mother-in-law to the Capitol. While the ladies sat by a fire in another room where glaziers were working, "Dr. T-n laid out an Oval, round which is to be the communication to the gallery of the Senate room." She did not note his doing anything like that again. The glaziers were working to close the building so work could continue inside during the winter. Hoban and his skilled workers would build the interior rooms. Thornton's drawing an oval on the floor was an exercise for his own benefit, but for what purpose; to help him visualize setting a tomb in the Capitol under the dome or oval rooms in a house?(9) As it turned out, he didn't share a sketch for a tomb until the end of February. He designed a house on February 1.

In late January, Navy secretary Stoddert sent a personal letter to Thornton castigating the commissioners for not properly preparing the President's house for the reception of the president: "A private gentleman preparing a residence for a friend would have done more than has been done." Stoddert wanted an enclosed garden "at the north side of the Presidents Houses" similar to one had by the richest man in Philadelphia, William Bingham. There also should be a stable, carriage house and garden house. The latter should be in a garden that would be "an agreeable place to walk in even this summer."

|

| White House in 1820 |

On January 30, Thornton wrote back that he had always been for grandeur throughout the city. His colleagues were "afraid of encouraging any expense not absolutely necessary, and seem not to think these things necessary that you and I deem indispensable." He then reflected on the mansion: "Some affect to think the house and all that relates to it are upon too extravagant a scale. I think the whole very moderate,..." He added that the president should get a salary of $100,000 to maintain it. At that time, he made $25,000. Thornton also sent a plan of the President's house to the president and noted that "the colonnade to the south is not completed at present, and temporary steps are to be put in."(10) As a president looked south from his mansion, he would see lots Thornton owned at the east end of Square 171.

Two days after he wrote that letter, Mrs. Thornton noted: "The ground covered

with the deepest snow we have ever seen here (in 5 yrs.) - river frozen

over. Dr. T- engaged in drawing at his plan for a House to build one day

or another on Sq. 171." He evidently finished the design on February 2. On the 4th, Mrs. Thornton "began to

copy on a larger scale the elevation and ground plan of the house."(11)

What Thornton drew suggests that he didn't design the Octagon. Mrs. Thornton's diary told a

simple story. Thornton didn't like Law's oval room. So he designed a house

with better oval rooms. His wife thought Law's house roomy and Tayloe's

wall handsome, so he showed her what a handsome and roomy house should

look like. The larger design with oval rooms in Thornton's papers, that is thought to be his first

take on the Octagon design, is likely his final design for a house on

Lot 17 in Square 171. Thornton designed a house to

rival Tayloe's and Law's.

A slope to the south toward the river precluded building on the western half of Square 171 until the area was leveled. A house on lot 17 at the angled intersection of New York Avenue and 17th Street NW would face the President's house. That left Thornton with the same problem that the architect of the Octagon and Law's house had solved. That meant he could copy Lovering's solution and out do it with a nobler house.

|

| from "historical map" published 1931 |

Thornton's design for Lot 17 in Square 171 would not have worked on Lot 8 in Square 170. An oval room in the rear of a house on Lot 8 would be hidden from view and have a view of the backs of buildings on F Street to the north that would block any view of the executive mansion. Thornton owned the lots southwest of Lot 17 and could preserve a view looking down the slope to the Potomac River. The large semi-circular portico on the front side of Thornton's design invited eyes looking down from the south portico of the President's house.

Table : Orientation of Thornton design if in lot 17 Square 171

|

|

Thornton's habit of studying floor plans and elevations in books before drawing his own suggests that he asked Lovering for one of his preliminary plans for the Octagon. If Lovering had followed the same pattern of trying to get a contract with Law and Tayloe as he would with Stier, then he made at least three specimens for each building, affording a client a choice of six solutions to the problem faced by building in an angled lot. That explains the other floor plan in Thornton's paper that resembles the actual Octagon floor plan.

In May 1800, Lovering placed an ad in the local newspapers: "William Lovering, Architect and General Builder – Begs leave to inform his friends and the public, that he has removed from the City of Washington to Gay Street, the next street above the Union Tavern in Georgetown, where he plans to estimate all manner of building, either with materials and labor, or labor only. Specimens of buildings suitable for the obtuse or acute angles of the streets of the City of Washington, may be seen at his home." In Building the Octagon, Ridout quotes the ad and characterizes it as a mere builder taking advantage of what he was learning while building a house designed by a genius: "Supervising architect William Lovering attempted to capitalize on his experience with the unorthodox plan of the Octagon by soliciting other commissions for the eccentrically shaped lots so common in Washington." However, Lovering's ad did not merely offer "his experience." He offered to share "specimens of buildings," that is, plans and elevations to illustrate what could be built on angled lots. Lovering was trying to get work based on his experience as a designer, not merely on his experience as a builder. That Thornton studied the plan only to design his own house would not bother Lovering. He knew Thornton might pay him for estimating the cost of the building if not actually building it. Thornton's asking for a specimen might have led Lovering to believe that there might be a demand for them, thus prompting him to place his ad.(12)

What Thornton drew adapts Lovering's configuration to different terrain with a house less convenient for a family but befitting his grandiose ideas to bring eclat to the city. But why didn't his wife say more about such a consequential design in her diary? She noted that he spent the day designing his house "to build one day or another." She stated the obvious which meant the opposite. This was not a project that might be done in the future, and couldn't be done at that time. W. B. Bryan offered an explanation for her lack of enthusiasm. She knew the house could not be built "owing, no doubt, to a lack of funds, which was a common experience in the life of a man who moved in a large orb, but one not within in the range of either the making or the saving money." There is something to that, but whenever Thornton sold his Lancaster property, he expected to make $40,000. The death of his mother in October 1799 might have led to some reckoning of the Tortola estate with money coming to Thornton.(13)

His wife didn't allude to a lack of funds. Money was always a factor but in this case Thornton's preposterous design for a house uncongenial to anyone who had to live in it made its realization equally unlikely no matter the day. A house designed for a rectangular lot would, even if done by Thornton, likely accommodate a live in mother-in-law and frequent house guests, and not stick out like a sore thumb. Mrs. Thornton had grown up in Philadelphia, an orderly brick city on a grid.

A little over three weeks after drawing an elevation for the house in Square 171, Mrs. Thornton was excited by one of her husband's architectural projects. On February 27, she wrote that "Dr. T. received a note from Mr. Law enclosing a rough Sketch of a plan for a Stables & c. behind his House which is five Stories behind and three before which Dr. T. promised to lay down for him, as he had suggested the ideas - The Stables & Carriage House are to be built at the bottom of the lot & the whole yard to be covered over at one story height & graveled over, so as to have a flat terrass from the Kitchen Story all over the extremity of the lot." That was her most elaborate description of her husband's designs.(14)

Two weeks later, a boy delivered a note "from Mr. Carroll of Duddington, (living in the City an original and large proprietor) requesting Dr. T- as he had promised, to give him some ideas for the plan of two houses he and his brother are going to begin immediately on Sq. 686 on the Capitol Hill." Thornton spent the afternoon "drawing the plans for Mr. Carroll." His design was likely an expansion of the General's design. Carroll offered the houses for sale in January 1801 and made more of the size of the lot than the character of the houses: "two three story brick houses adjoining each other, 28 feet front each, by forty feet deep - a fine commodious lot 61 feet front, by 196 feet deep, running back to an alley 30 feet wide, and may be occupied as one or two tenements, they are finished in a plain but substantial manner, and built of the best materials...." Those paired houses were larger than the General's which likely pleased Thornton. They also would test Thornton's assumption that the General could have methodically sold his houses to finance the construction of more until a row of houses filled the street. Carroll's houses didn't sell, which left him with the option of renting them to someone who wanted to operate a boarding house.(15)

In Building the Octagon, Ridout ignores Thornton's design for his own house and cites Thornton's design for Carroll as evidence that he designed a house for Tayloe in 1797, 1798 or 1799. He makes a good point: that Thornton designed a house for another gentleman is significant. However, Carroll and Law didn't ask Thornton for a design because he was a talented architect. They wanted to flatter him because he was a commissioner. Through her nephew William Cranch, who was then Law's lawyer, they learned that Mrs. Adams had doubts about moving into the President's house. She feared the building would be too green. Law wrote the letter to James Greenleaf that not only recounted the General's reaction, but also listed the dimensions of the oval rooms and sketched its fan-shaped kitchen. Law asked Greenleaf to see that Mrs. Adams got the letter and it wound up in the Adams Family Papers. Cranch thought Carroll's mansion better suited and Carroll sent a letter to Cranch describing his house, and Cranch sent it to his aunt. Having Thornton on their side could do neither Law nor Carroll any harm, if the First Family needed a house. Coincidentally, through Notley Young, another member of the Carroll clan, Bishop John Carroll asked Thornton to submit a design for a new cathedral in Baltimore. He also asked other architects and eventually chose Latrobe's design.

Then the First Lady leaned toward not coming to the city at all. Congress gave the cabinet money and power to prepare the city for the government. Everyone knew that congress would soon abolish the board of commissioners. The Constitution gave congress exclusive jurisdiction over the city and its public buildings. Both Law and Carroll continued to build houses in a vain effort to profit off their many building lots in the city. Other men, including Hoban, designed their houses. There is no evidence that they again asked Thornton for building plans.(17)

Finally, Thornton undertook another project that promised to be the most rewarding but likely wasn't. After the General's death, Thornton continued to be welcomed at Mount Vernon. While there in early March 1800, he showed Lawrence Lewis where to build his house. On August 4, 1800, while they were at Mount Vernon, Mrs. Thornton described a pleasing day: "Dr. T. and Mr. Lewis played at backgammon till tea. After breakfast - Mrs. Lewis, the young Ladies and I went in Mrs. Washington's carriage ( a coachee and four) and Mr. Lewis and Dr. T. in ours, to see Mr. Lewis's hill where he is going to build his farm, mill and distillery. Dr. T. has given him a plan for his house. He has a fine situation, all in woods, from which he will have an extensive and beautiful view." She described the scene but not her husband's plan, but she did mention it. Evidently, the money the General set aside for Lewis was slow to become available. Two wings went up first. The building connecting them which likely bore the brunt of Thornton's genius was delayed until 1804 and the builder thought it too close to the down slope. In an 1817 letter to Jefferson, Thornton described how in Virginia columns of bricks were "plastered over in imitation of freestone." He did not claim credit for the process nor further described his design for Lewis. Lacking oval rooms, C. M. Harris has no interest in it: "the house as it appears today has no resemblance to Thornton's other designs." Thornton also seemed to lose interest in the Washington family. In 1801, Law turned on him for supporting the West side the city. Thornton passed on malicious gossip about Mrs. Law. After Mrs. Washington's death in 1802, Thornton "was sorry that the Heirs of such a man should have acted so unworthily" as they divvied up the General's belongings and clothing. Mount Vernon lost its attraction. However, the Thorntons and Peters remained best friends.(18)

There is no documentation of Thornton designing another house until 1808 when, in the calendar-like notebook that she kept, Mrs. Thornton noted that he drew a plan for "Mr. Peter." Her annual notebooks are extant for the years 1803 to 1815, and the one other mention of his making a plan occurred in 1811. His biographers excuse themselves from explaining Thornton's retreat from designing houses by explaining that upon appointment as Commissioner of Patents in June 1802, he no longer had time for great architecture.(19) A better explanation is that in reaction to the interest the General took in Law's and the Tayloe's houses, added to the General denying him the privilege of designing his Capitol Hill houses, Thornton set out to prove to himself, his wife, the General's family including Messrs. Law, Lewis and Peter that he could design houses. Not set on having a career doing so, what he designed for them and Carroll in 1800 was sufficient. Other friends would have houses built and evidently they never involved Thornton.

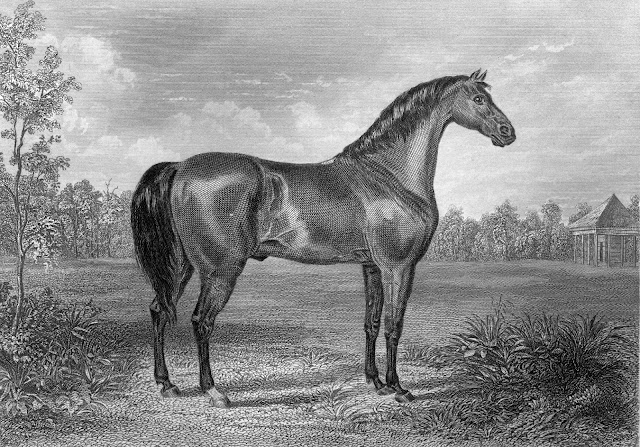

In 1799, one of Tayloe's seven sisters married one of the General's nephews, but, of course, that is not why Thornton was interested in Tayloe. On January 24, 1800, on his way from Mount Airy to Annapolis, Tayloe sent a message to Thornton who was at Philip Fitzhugh's seat trying to get him to take a filly and share profits from the sale of her future foals. While returning home after a tea in Georgetown, Mrs. Thornton bumped into her husband on the way to Georgetown to see Tayloe at the Union Tavern. The doctor got back home at 9 pm. Tayloe had to get an early start for Annapolis in the morning. When in Annapolis, Tayloe graciously helped determine the legal status of property in Georgetown owned by Thornton's sister-in-law who lived in the Virgin Islands. They evidently also talked about horses.(20)

In her February 16 entry, Mrs. Thornton counted 23 horses that they owned including Driver "now at the farm to be sent to Mr. Tayloe's in Virginia to run." In her March 13 entry, she reported that their slave Joe Key, an enslaved jockey named Randall borrowed from another breeder, Driver and a three year old Sorrel filly, "which Dr. T has exchanged with Mr. Tayloe," set off for Virginia. "Joe took a letter from Mr. Tayloe to the manager of his iron works in Neabsco directing him to send a man with Randall to his seat. Took with them cornbread and meat to save tavern expenses." Key would return to F Street; Driver and Randall would be trained to win races. Tayloe used slaves as jockeys, an idea that Thornton embraced.(21)

In the spring 1800, Thornton entered the informal Maryland brotherhood of breeders. Page 4 of the April 7, 1800, Federal Gazette and Baltimore Daily Advertisers was full of its doings. An advertisement offered the stud services of "The Celebrated Running Horse Clifden, imported from England last autumn by William Thornton, esquire, of the city of Washington...." On the same page, a notice from the commissioners was signed by Thornton. But Tayloe dominated the page. There was a longer ad offering the services of Mufti, "imported last August by John Tayloe, esquire, of Mount Airy;" a long ad about Ranger noted that he had beaten Ridgely's Medley who "ran a dead heat with Major Tayloe's Leviathan, who is thought the best horse in Virginia;" and, most interesting to Thornton, a letter from Tayloe certified the pedigree of Dunganon and that he was sold "out of training for 500 Guineas."(22)

Profiting off their horses that year took on added importance because money did not come from the Tortola plantation as it usually did. Thornton needed a loan from Thomas Law to cover $2,358.43 due in 75 days for a bounced check and hefty penalty. However, he expected consideration from Tortola and didn't stint in his entertaining newcomers to the city. The Thorntons also expected Driver to return ready to race and win purses. Then, in her June 18 entry, Mrs. Thornton wrote "Driver returned from Virginia in the Afternoon, lame and in bad plight."(23) If Tayloe came to the city or Georgetown again while his house was being built, she didn't mention it her diary.(24)

However, a sentence that she wrote in her diary in late November suggests that her husband still had a relationship with Tayloe and his house: "Dr. T came at one o'clock for us to go see the chimney pieces at Mr. Tayloe's house." The chimney pieces were made of artificial stone by the Coade Company in London. Since the address of the company is printed in one of Thornton's notebooks, Harris assumes the chimney pieces as well as an iron stove from Carron Iron Work near Edinburgh "likely reflect Thornton's specific recommendations." While touring with Faujas in 1784, Thornton visited the Carron works. Of course, Tayloe was educated in England and no stranger to the stoves of his rich friends. Lovering had worked in London. Harris notes that in a 1797 letter to Nicholson, that Lovering mentioned using Coade stone in a house he built on Greenleaf's Point. In early December, Mrs. Thornton found time to see them but wrote nothing about them, the interior of the house, or her husband having anything to do with it. Tayloe's weren't the only chimney pieces that Thornton went out of his way to see in 1800. Back in May, she noted that her husband previewed a sale of chimney pieces at Tunnicliff's hotel.

Ridout takes another tack to associate Thornton with perhaps the most photographed decorative element in the house. Glenn Brown, by the way, thought Thornton designed them. As it turned out, not all of the Coade shipment arrived which, in July 1801, prompted Tayloe to head a letter to Coade: "Mr. Coade - ought to be Mr. Shark." In September, George Andrews, an ornament maker that Thornton hired to ornament the interior walls of the President's house, came to the rescue. That convinces Ridout that "Thornton can doubtless by credited with Andrew's employment at the Octagon." However, since May, Andrews had been advertising that he made chimney pieces and his "Composition Manufactory" was "in the rear of the President's house." Dorsey and Lovering likely noticed him.

While Ridout and Harris make much of the chimney pieces, they more or less ignore the stable. Ridout suggests it was designed and built in 1801. Judging from the handwriting on an extant plan, Lovering drew the floor plan and elevation for the two story brick stable and coach house. Judging from Mrs. Thornton's diary, Thornton was more interested in horses than he was in chimney pieces, and knew that Tayloe shared that interest. Thornton had designed a stable for Thomas Law.1 Of course, there had to have been a rough patch in the Thornton-Tayloe friendship after Driver returned from Mount Airy in bad plight. It explains why Mrs. Thornton wrote so little about Tayloe after June 18th. It could also explain why Thornton would have declined any invitation to design Tayloe's stable. However, likely he didn't think of asking Thornton for a design, just as he never asked him for a house design. The best evidence for that is how and when Thornton broadcast his reaction to Driver's bad plight.(25)

In May 1801, Tayloe lost his election for a congressional seat by 307 votes, but it wasn't close. There were only 1107 voters. Defeat must have stung because he arranged another way to add eclat to his making the federal city his family's winter home. In December 1801, he heralded his arrival in a signed notice in the Washington Federalist newspaper. He become a resident of the City of Washington "on or about" January 10, 1802. That meant his house was effectively finished, but that was not the point of the notice. In it, he announced that he invited a match race with anyone and "can be accommodated, for his own sum, not less than $1500." William O. Sprigg responded and a match race for $3000 was scheduled for May 13. Sprigg's horse had beaten Tayloe's in the city's first Jockey Club races in November.(26)

Thornton could not accept the challenge. After a stint with another trainer, Driver was still in no shape to race. Thornton blamed Tayloe. Beginning in early April 1802 and continuing through June, a long newspaper announcement offered Driver as a stud and suggested that Tayloe ruined a horse that would surely have been one of the greatest racers:

Driver

was never tried but once, by John Tayloe, esq., at Tappanoe in Virginia

when the bets were in favor of the winner (Yaricot) distancing the

field; but Driver lost one heat by only a few feet, and the other heat

by only four inches, in three mile heats, distancing the other horses;

which as Driver, like his celebrated sire, is a four mile horse, was

thought a great race, especially as he was much out of order in

consequence of a bad cough. Col. Holmes [probably Hoomes] told me he was

thought by those who saw him run, one of the best bottomed horses in

America, or perhaps in the world. Driver was put into training the last

autumn, but met with an accident that prevented his starting; however,

he proved one of the fleetest horses Mr. Duvall ever trained, and of

ever lasting bottom.

By "bottom" was meant staying power and stamina. While the ad didn't blame Tayloe for sending Driver home in "bad plight," later in the ad, Thornton quoted Charles Duvall as saying: "if I had trained him at four years old, I think he would have made the best horse on the continent...."(27)

Tayloe

was new to the city and disposed to make friends with all local rivals

on the turf. For

years, he had offered to improve blood lines in America and train and

race horses ultimately for every sportsman's benefit. He founded the

Washington Jockey Club. Thornton's advertisement undermined all of that.

That he held fire until Tayloe moved into the Octagon and solicited a

match race proves that Thornton did not have anything to do with the

Octagon. He aimed to embarrass Tayloe. Their friendship had ended on

June 18, 1800.

Tayloe made amends in 1803. If Mrs. Thornton kept diaries in 1801 and 1802, they have been lost. From 1803 through 1815, she kept track of expenses, income, and briefly noted visits and visitors. On March 7, Mrs. Thornton noted that "Joe returned in the evening with a horse called Wild Medley." Then an ad offering the services of Wild Medley ran in the Washington Federalist, but it was not written by Thornton. It noted that the horse was bought in Virginia by "W. Thornton." The ad included a testimony signed by Tayloe certifying the wonders of a filly got by Wild Medley that handily beat Tayloe's horse. Another worthy attested that Tayloe bought two foals got by Wild Medley for $1200. Another lamented that its greatest horse had left Gloucester County which is nestled along the Virginia shore at the wide mouth of the Potomac River. Likely Tayloe bought the horse and gave it to Thornton. Judging from Mrs. Thornton's notebooks, the friendship between the Thorntons and Tayloes blossomed, thanks to Thornton's obsession with horses.(28)

How does one measure his obsession? In the summer of 1811, Thornton suffered his longest bought of fever. His doctors called it a rheumatic fever. He must have had a stomach complaint too since Tayloe brought him soda waters on July 31 and came again on August 2. He was bedridden for almost two months and thought to be at death's door for most of July. On August 11, after a visit from a Col. White who trained his horses, he summoned up the strength to dictate a letter to the president. Thornton had probably imported King Hiram in 1805 for his pedigree not his victories. He got a colt for Madison in 1807. Thornton asked Madison to send the colt to be trained by White. If he won races, that would increase the value of King Hiram. He closed the letter by confessing "I am so fatigued by only dictating these few lines that I must bid you an affectionate and sincere adieu."

In 1806, Tayloe cut back on his personal involvement in racing. As for breeding, the 1910 Encyclopedia Britannica credited Tayloe's Sir Archy for founding "a family to which nearly all the blood horses of America trace back."1 According to the 1827 US Supreme Court decision in Thornton v. Wynn, Thornton vied to best Tayloe in both realms. In 1821, Thornton bought a horse for $3,000 that was touted by the seller as "capable of beating any horse in the United States" and capable of a match with Eclipse. In 1821, Eclipse's victory in New York over a Virginia horse bred by Tayloe made him the most talked about horse in the nation's history. Col. Tayloe bred Rattler and Col. Wynn trained him, but if Rattler won the featured Washington Jockey Club race, Thornton might have easily received the backing of Southern sportsmen to arrange a match race with Eclipse. On race day in Washington, Thornton not Tayloe was the contender vying for a place in the history of the American turf. Rattler pulled a tendon and lost. Then while the courts adjudicated if Thornton still had to pay for the horse, he offered him as a stud. In an 1822 broadside, Thornton proved that Rattler was the better stud. Not only was Rattler gotten by Sir Archy but Rattler's dam Robin Red-Breast traced her pedigree back to old Highflyer just as Sir Archy did. Ergo, Rattler's pedigree was better that Sir Archy's because of a "double cross... Rattler is doubly descended from old Highflyer."(31)

All that said about his obsession, it did not necessarily take much of his time. There is no evidence that Thornton supervised the training his racehorses himself and he had a farm manager and slaves to address their daily needs. Judging from her notebooks, Mrs. Thornton kept track of where Thornton's horses were "let," how much they made for their stud services, and when they died, which always seemed to shock her. After all, they were investments and longevity was paramount. Also, the sport of horse racing did not create a milieu which might prompt rivals to gain an advantage by bragging on their other attainments. When Thornton's horse lost a race, he would offer a scientific explanation but not reveal that he designed an Octagon.

However, the Octagon made history toward the end of the War of 1812 so did Thornton. If Thornton had designed the Octagon that fact should have been branded by the flames that imperiled the city. President Madison and family moved into Tayloe's house on September 8, two weeks after the British burned the President's house. Congress moved into the Patent Office, then in a corner of Blodget's Hotel bought by the government in 1810. The Patent Office was available because Commissioner of Patents Thornton persuaded British officers to spare it from the flames and the "Museum of the Arts" that it housed, i.e. patent models, from the flames. By the way, the models were mostly useless, including a musical instrument being crafted to Thornton's specifications, By meeting in the Patent Office, those arguing that congress should convene in another city could not point to the lack of a meeting room.

Because those wanting move out of city were stymied, Thornton claimed credit for saving city. In the aftermath of the Battle of Bladensburg, that Thornton avoided by fleeing to Georgetown, he visited a wounded British colonel named William Thornton. That inspired Thornton to congratulate himself for saving the Patent Office in the wittiest way. In a letter to Col. William Thornton who had since gone on to greater things in Britain, Thornton shared his mot that he claimed had spread throughout the city "One William Thornton took the city and another preserved it by that single act."

President Madison and his cabinet knew better. When the president returned to the city, Thornton followed him on horse to the Navy Yard and explained to him that its citizens wanted to capitulate if British troops then on ships off Alexandria came to the city. He argued that the people had the right to surrender the city even though the government had returned. Col. James Monroe, who was at the president's side, threatened any citizen who stepped forward with a bayonet in the back. Mrs. Thornton had resumed her diary and expressed alarm as her husband grabbed a sword and tried to rally citizens to defend the city. In a letter to the National Intelligencer, Thornton denied that he wanted to capitulate, but, as the same time made other enraging claims. As a mere Justice of the Peace, he brought order to the city after all other officers of the government had fled. Mrs. Madison was not amused. When the Madisons left the city at the end of his second term in March 1817, Mrs. Madison visited all her friends but not her old neighbor Mrs. Thornton. The doctor called the retiring president's attention to that and allowed that he also had noticed "a marked distance to coldness" in their relations.(30)

Lovering could not brag that a house he designed provided a home and office for the president. He died in 1813. Of course, there would no need to cite a horse's pedigree as evidence that Thornton didn't design the Octagon, if Lovering had been more explicit about specimens he drew to face intersections with an acute angle. Evidently, in that day no one wrote about who designed a house, not even the designer. However, in 1807, master carpenter Andrew McDonald advertised his services with this reminder. He had "finished the buildings on Rock Hill, near Georgetown, for the late Gustavus Scott, esq...; and also finished that elegant building belonging to Colonel John Tayloe..." So, why didn't Lovering associate his name with Tayloe's house? Lovering probably decided that he could not publicly claim his design because that would diminish the glory of house owners like Tayloe, Law and Stier. Instead, he had to rely on their good word, which he probably never heard. On June 14, 1801, Tayloe wrote to Lovering: "my Object is to be done with the building as quickly as I can with the least trouble and vexation - for the expense of it already alarms me to death when I think of it." Dorsey calculated that the project cost $28,476.82 well over the contract price of $13,000. That should temper modern claims that it was "constructed with enslaved labor." By the way, in that letter Tayloe demanded that McDonald be fired. Stier also became vexed at Lovering because of delays in building his house. In a letter to his son, Stier called Lovering a "blockhead."(32)

In his future advertisements, Lovering he did not reveal what he had designed or built. In an April 1801 ad, he claimed that he had "been in the practice of drawing for and superintending great part of the buildings in the City of Washington and vicinity." But he didn't say which ones. In an 1804 ad, he announced that he had relocated to Alexandria, Virginia, "where he Draws, Designs, and makes estimates of all manner of Buildings and also MEASURES AND VALUES all the different work connected to the building art." He was ready to "contract for any building and complete the same, from a palace to a cottage, which will be executed in the most masterly and economic style." He claimed he had "long experience" but didn't list any houses he designed or built. In 1809, he placed an ad in Baltimore, which exuded a complete command of his profession: "Begs leave to inform the gentlemen of Baltimore and its environs, that they may be supplied with plans, elevations and sections of any building intended to be erected, with the estimates of the different work particularized in a manner in which it is impossible for any dispute to arise, and gives instructions to the different workmen that they have no occasion to make any inquiry during the execution of the building." He also offered to build and added: "his abilities may be known by resorting to different works which he has executed..." Lovering mastered his profession and left his mark on houses throughout the federal city then he moved on to Baltimore, Philadelphia and back to Baltimore where he died in 1813.(33)

His modern reputation for architectural design suffers because he built too many houses. He may have been ingenious but there was no intellectual underpinning let alone consistency to his innovations. Lovering solved problems. He didn't shape a house to make a statement. While commiserating with Robert Morris over the cost of building twenty buildings in three months, he hit on the idea of saving on bricks by giving corner houses a huge store front window. When commiserating with John Nicholson about two story houses not commanding a high enough sales price, he suggested three story houses with dormer windows which would essentially cost as much as a two story house to build but sell or rent for 25 % more. Then he worked with Law and Tayloe who faced angles and had more money than Morris and Nicholson.

Generally speaking, neo-classical designs created problems and the Capitol was certainly not an exception. Thanks to its oval rooms, the Octagon can be rated as neo-classical. Touting the genius of Thornton makes that more plausible. The latest on-line description leaves no doubt of that:

This three-story brick house breaks with the traditional late Georgian and early Federal house planning that preceded it. Many of the leading European architects of the late 18th century sought to achieve a new direction in architecture through a design philosophy that sought to combine simple, basic geometrical shapes while using a minimum of unnecessary decoration. Thornton, the Octagon’s architect, traveled extensively in both England and in France and was no doubt alive to this philosophy. Presented with a building site that did not lend itself readily to a stereotyped solution, Thornton took full advantage of his opportunity and brought to the new Federal City a building of startling freshness and originality which has never been surpassed.

Fitting Lovering into that mold is impossible.

Of course, who designed the Octagon was unimportant to Thornton. He never claimed that he designed it. He focused his claims on the Capitol. In her 1800 diary, Mrs. Thornton left no doubt that her husband was the author of the Capitol. Unfortunately, she didn't lend a sense of urgency to that mission. For example, the same week he drew the design for Lot 17, Mrs. Thornton noted: "Dr. T- at work all day on the East Elevation of the Capitol. I assisted a little 'till evening then worked on my netting." Was he merely making a copy of his elevation anticipating that congressmen would ask for a copy to inform their deliberations? Or was he making minor changes to ornaments that adorned the walls? She didn't leave a clue either way. Then, he got a harbinger that all was well and his future fame assured.

In late April 1800, Vice President Jefferson wrote to Thornton sharing ideas about the Senate chamber, especially the position of the seat for the presiding officer, i.e. the vice president. There is no evidence that Thornton had any contact with Jefferson since 1794. However, in his 1797 letters to England, Thornton did brag on his friendship with Jefferson and Madison. The Vice President could have addressed his concerns to the commissioners, or to Navy secretary Stoddert who was distributing the $10,000 appropriated to prepare the city, or to Thomas Claxton, the Doorkeeper of the House of the Representatives sent by the Speaker to make arrangements both for the Senate and House. But Jefferson not only wrote only to Thornton but assured him that he wasn't pulling rank on him and that he recognized that Thornton alone made final decisions about arrangements in the Capitol: "I pray you to consider these hints as written privately to yourself, and as meant to have no other weight than your own judgment may give them."

Jefferson asked one direct question: "Are the rooms for the two houses so far advanced as that their interior arrangements are fixed & begun?" One would think Thornton would jump at the opportunity to go back and forth with the man he hoped would be the next president. But with an eye to his legacy, rather than making the building more convenient for those obliged to use it, he jumped at the opportunity to confirm the supremacy of his plans. He simply thanked Jefferson for his "kindness in suggesting several important considerations respecting the Arrangements in the Capitol & I have the satisfaction of informing you that they are so nearly consonant to my Plans that what I had directed will I flatter myself meet with your approbation...." He filled out his letter to Jefferson, who was president of the American Philosophical Society, with his theories on the prevention of yellow fever epidemics.(34)

But, in late April 1800, were interior arrangements fixed? In his April 17, 1799, letter to the board, in which he had declined making drawings for finishing the Senate chamber, he didn't discuss the placement of Jefferson's seat or any other issue that Jefferson would raise in April 1800. A month after sending his reply to Jefferson, Thornton met with Claxton, who, Mrs. Thornton wrote, "is empowered to procure the necessary furniture for the Capitol." Then, "they sent for Mr. Hoban and were consulting respecting the seat for the President of the Senate." She left it unclear if Thornton and Claxton sent for Hoban to receive Thornton's orders or Claxton's, or perhaps Hoban explained to both where the seat had to be. What is clear is that Thornton did not carry on a consultation about the chair with the first man who would sit in it. It is not clear if Thornton ever made a plan showing the internal arrangements of the Senate chamber.

Two months earlier, Thornton did take pains to make clear that he designed the capitals for the columns inside the Senate chamber. On February 10, the plasterer John Kearney asked for a drawing of the ornaments for the tops of the columns circling the interior of the Senate chamber. According to its proceedings, written in Thornton's hand, "the Board direct James Hoban to furnish him with, in conformity to the drawing given to John Kearney by Wm. Thornton - in the ancient Ionic stile, but with volutes like the modern Ionic." In a footnote to the Papers of William Thornton, Harris highlights the proceedings that he thinks made clear that Thornton was directing Hoban, and made a drawing to inform a working drawing to be made by Hoban. However, the Superintendent may have been confused. On February 15, 1800, Mrs. Thornton noted that Hoban called on her husband after dinner to "consult about the Capitals...."(35)

Surely, Thornton was on the scene and could talk and write about arrangements in the Capitol. With support of one colleague on the board, he could direct what must be done. However, despite expressing an inclination to do so since 1796, Thornton had not drawn comprehensive plans with attendant details depicted. At the same time, he never wrote a comprehensive description of what had been done. In early 1900, W. B. Bryan asked Glenn Brown to give a paper before the Columbia Historical Society describing the North Wing when congress convened there in December 1800. He based his paper on a report Hoban wrote, but, of course, Brown insisted that what Hoban described were the fruits of Thornton's genius.(36)

Thornton did not want to change his plan to suit others. He simply wanted it endorsed as the plan. In June, President Adams visited the city, Georgetown and Alexandria and attended all public dinners in his honor. So did Thornton, who managed to corner him. Adams promised to drop in and see his design for the Capitol. Whether he sensed that Thornton would seek his official approval for the design is unknown, but at the appointed hour, his chariot and four roared by the F Street house without stopping.(37)

Thornton thought of another way to acquaint the president with his genius. During the summer, he met a better ornament maker from Baltimore, George Andrews. Thornton confessed to Stoddert that he couldn't muster enough of the board's hired slaves to beautify the grounds of the President's house. Instead he worked with Andrews to put composition ornaments on the interior walls of the house. Thornton came up with the designs. On November 1, President Adams arrived to occupy his house. That same day, the commissioners received a note directing that all the ornaments depicting men or beasts at the President's house be removed and replaced with ornamental urns. Adams' ire was not personally directed against Thornton. Mrs. Adams returned a visit by Mrs. Thornton and saw the plan. Advised by Cranch, he appointed Thornton one of the 28 justices of the peace for the District of Columbia which allowed to continuing adjudicating petty crimes and small debts and notarize deeds as he had been doing as a county magistrate.(38)

Meanwhile, Thornton lobbied the House to put the General's tomb under the future dome. In early December, the Intelligencer printed portions of the letter he had sent to Blodget in February that described a "massy rock" inspired by the monument to Peter the Great in St. Petersburg. The sculptures on the rock featured the General ascending to heaven on top, and, among other figures, a woman with a snake coiled around her body, symbolizing eternity, on the bottom. The bodies of the General and his wife would be entombed in the middle and all that would be under the Capitol's dome, once it was built. There is no evidence that his proposal had any influence on the debate which focused on a mausoleum to be outside the Capitol.(39)

Then, before adjourning on Inauguration Day, March 4, 1801, the House authorized a chamber of its own as soon as possible. Commissioner Scott died on Christmas Day, making Thornton the senior member of the board. Commissioner White bowed to Thornton's leadership in architectural matters. The board decided to build a chamber for the House on the site of the South Wing. While it would be temporary, its foundation and walls would be incorporated into the permanent South Wing. Once again Thornton didn't mind Hoban making the design, with the caveat that he follow Thornton's plan and make a building elliptical in shape on the foundation already laid. Hoban drew a three plans and estimated that the cheapest temporary "elliptical room" would cost $5,000 but only $1,000 of it would have to be torn down when the South Wing was built.

President Jefferson, who expected to see his Halle au Bles ideas embodied in Thornton's room, agreed with that approach with a caveat offered by Hoban. He wrote to the commissioners: "mr Hobens observes there will be considerable inconveniencies in carrying up the elliptical wall now without the square one, & the square one in future without the elliptical wall, and that these difficulties increase as the walls get higher." For that reason, the president only approved one story for the moment. The board hired Lovering as the contractor. He had designed and supervised construction of oval rooms in Law's and Tayloe's houses. The Seventh Congress convened on December 7, 1801, in what Thornton called "the elliptical room." Even though it was 90 by 72 feet, members soon called it the "oven," either because it was stuffy or its contours resembled a Dutch oven. Now treated as an amusing sidelight, the elliptical room was a second step, after laying the foundation in 1795, in the fulfillment of Thornton's plan for the South Wing.(40)

What was likely more gratifying to Thornton, was how easily decisions were made with the president living in the city. He saw the problem, recognized that Thornton's prize winning plan had the solution and that Thornton and Hoban worked well together. Before the president moved to the city, Thornton did not enunciate what was clearly on his mind. He thought he could fulfill the obligations of the design contest winner without also being a commissioner. When Jefferson did give him another job, he would indeed consult with him about the Capitol design even though he was no longer a commissioner. On Inauguration Day, Thornton applied to the president to fill any vacancy.

Congress did not pass the bill abolishing the board of commissioners until April 1802 and that relieved the president from having to find another job for Thornton. At the same time, much to the chagrin of his partisans, the president did not dismiss all current office holders appointed by Washington and Adams. However, Thornton had befriended the Treasurer of the United States, with a $3,000 a year salary, learned when he planned to retire in September and asked his old friend Madison to send and endorse his application for the job to the president. The request came at the culmination of Thornton's doing a service for Madison. He had first offered the incoming secretary of state accommodation in his F Street house. Then he learned that the president was trying to find a rental for Madison. Thornton took over that task and in August advanced rent for a house being built next to his in return for an agreement that the builder would pay $1,000 if the house wasn't ready on October 1. In early August, the builder had advertised that he wanted to hire laborers to work until November 1.

Just as in his letter to the General describing how he directed Blagden's workers to replace wooden sills with stone, so he claimed that he gave directions to the builder next door, telling Madison that: "I have directed the third Story to be divided into four Rooms, two very good Bed-chambers, & the other two smaller Bed chambers. The Cellar I have directed to be divided, that one may serve for wine &c, the other for Coals &c—and for security against Fire a Cupola on the roof...." Madison expressed his gratitude, but did not endorse Thornton's application. On the basis of Thornton's letter, C. M. Harris claims that Thornton "supervised the construction" of Madison's rental. Thornton certainly made a rhetorical show of it but there is evidence that Madison was disappointed in what he found in October. In August, he had emphasized to Thornton that he needed a good stable. In June 1802, Madison finally signed a rental agreement with the builder on condition that he build a brick stable and "what remains to be done to the dwelling house shall also be finished."

When congressmen returned to the city in the fall of 1801, the president replaced the retiring Treasurer with a Virginia M. D. who was also a Revolutionary War veteran.(41) Thornton had to assume that the president simply wanted him to continue what he had been doing. When congress abolished the board it assigned its duties to a new Superintendent of the City, to be appointed by the president. With Scott dead, his replacement a Federalist, and White anxious for a judgeship, Thornton had to expect that he would be asked to become the superintendent, certainly his wife did. Before disbanding, the board advised the president about decisions he should make. On April 17, Thornton sent a long letter to the president addressing the problem of a Water Street running along the entire waterfront of the city. Commissioner White had already written to the president doubting the "propriety" of Thornton's grand ideas. The president agreed with White and perhaps Thornton's letter, in which he pointed to the Bordeaux waterfront as a good example, wearied the president. Still, Thornton and his ladies could delightfully fill out a table. A few days later, he invited all three to dinner.(42)

On June 1, the president made Thomas Munroe, the board's clerk, the new Superintendent. Mrs. Thornton asked him why he didn't appoint her husband. The president assured her that the job was temporary. Munroe held the job until 1815. But Thornton was not forgotten. Before its second session in the city ended in 1802, congress delegated its authority to grant patents to the State department. On June 2, 1802, the president and Madison hired Thornton as the clerk to process patents. He held the job until he died in 1828. There was one problem with his new position. The salary was very high for a clerk but not for a federal officer, only $1400. After 8 years of government service, he took a 12.5% cut in salary. The president was conscious of his slighting Thornton so he also appointed him one of the bankruptcy commissioners for the District of Columbia and calculated that Thornton would make $600 a year in fees. Thornton later claimed that out of pity for bankrupts, he never asked for fees. But with friends in high office, he trusted there would be more honors and emoluments. There weren't, and by 1812, he was a rather bitter bureaucrat, and more bitter still because in the meantime he lost control over his Capitol design despite Jefferson's continued respect for it.(43)

|

| Latrobe's Baltimore Cathedral |

|

| Carroll's Row |

|

| Thornton's "massy" tomb |

|

| Chimney piece in 1896 |

1. Lear Journal, Clements Library. Harris, p. 528; Thornton did not date his brief recollection of his patron’s death. However, in it he described Thomas Law as the brother of Lord Ellenborough. The latter Law became a Lord in April 1802 and died in 1818; Thompson, Mary V. "Death Defied" Mount Vernon Museum; Jefferson's weather observations , page 25.

2. WT to Marshall 6 January 1800, Harris p. 526; Mrs. Thornton's diary p. 92.

3. Harris p. 585; Diary p. 92.

4. Diary pp. 90, 92.

5. Commrs to Adams, 21 November 1799, Commrs. records; White to Adams 13 December 1799 (the editors of the on-line papers transcribed "Taylor" but the letter clearly reads "Tayloe;") Stoddert to Commrs., 3 January 1800, Commrs to Adams, 7 January 1800, Commrs. records; White to Adams, 15 January 1800; Washington Federalist, 28 February 1807 p. 3.

6. Diary pp. 90, 94, 97

7. Harris p. 586; Scott, Creating Capitol Hill p. 129.

8. WT to Fothergill 10 October 1797, Harris pp. 424-27;

9. Diary p. 91.

10. Stoddert to WT 20 January 1800; reply 30 January 1800, Harris p. 532-3.

11. Diary p. 102.

12. National Intelligencer, ad dated 1 May 1800; Ridout p. 123.

13. Bryan, History of National Capital, vol. 1, p. 346; WT to Madison, 2 September 1823.

14. Diary p. 112.

15. Diary p. 116; National Intelligencer 5 January 1801, p. 4 & 1 February 1802.

16. Ridout p. 29; Harris p 581.

17. A. Adams to Cranch, 4 February 1800 footnote 3; Law to Greenleaf 9 April 1800; see also Abigail Adams to Anna Greenleaf Cranch, 17 April 1800.

18. Diary pp. 176-7; Harris pp. 582, 591; WT to Jefferson 28 July 1802, 27 May 1817.

19. Harris, Liii; Gordon Brown pp. 43, 68. Brown thinks he worked long hours, but if he did, it was self-imposed. The law did not require that he evaluate inventions; AMT notebooks May 2, 1811.

20. Diary pp. 99, 107;

21. Diary pp. 107, 116-7; Cohen p. 114.

22. Federal Gazette and Baltimore Daily Advertisers, 7 April 1800, p. 4.

23. Diary p. 106; on timing of Tortola payments see Mrs. Thornton's diary 17 February p. 108, 14 April p. 129; Diary p. 157.

24. Diary pp. 133, 161, 168, 203, 205.

25. Harris p. 585; Diary pp. 141, 215.Ridout, pp. 70, 91

26. Tayloe ad Washington Federalist 22 December 1801; Sprigg ad 16 & 29 January 1802;

27. National Intelligencer 5 April 1802 p. 3.

28. AMT notebook Vol. 1 image 133; Washington Federalist 29 April 1803

29. Hunsberger p. 69; Julia King, George Hadfield: Architect of the Federal City

30. National Intelligencer 7 September 1814; Journal of Columbia Historical Society, 1916, "Mrs. Thorntos Diary Capture of Washington" pp. 177, 181; Monroe to Hay, 7 September 1814 ; National Intelligencer, September 8, 1814, September 10, 1814; AMT papers, Box 4 reel 1 Image 7; WT to Col. WT, 24 June 1815, Gilder Lehrman Institute, (no longer available without registered log-in); WT to Madison 3 March 1817; The Madisons did not stay in the Octagon for the remainder of his term. They found the house unhealthy and left it for one of the Seven Buildings on Pennsylvania Avenue, see Dolley Madison to Hannah Gallatin 29 December 1814;

31. Thornton v. Wynn 25 US 183; Rattler Broadside

32. Washington Federalist, 28 February 1807 p. 3; John Tayloe letterbook, quoted in Kamoie dissertation p. 200 footnote; Callcott, Margaret, editor, ...Letters of Rosalie Stier Calvert, p.29.

33. Natl. Intelligencer 8 May 1801; Alexandria Daily Advertiser, vol. 4, no. 1060, page 4, 11 August 1804 ; American Commer. Adv. 17 June 1809; Poulson's Amer. Daily 23 September1809; Diary p. 181; Baltimore City Directory. 1810, p. 117; AMT notebook vol. 3 image 124.

34. Diary p. 102. Jefferson to WT 23 April 1800; WT to Jefferson 7 May 1800;

35. Diary p. 134; Diary p. 107; Harris, p. 490.

36. Glenn Brown, "The United States Capitol in 1800." CHS Journal vol. 4.

37. Diary pp. 151ff.

38. Commissioners to Andrews, 1 November 1800; Thornton then arranged for Andrews to show Jefferson his samples, Diary pp. 208, 214, 222. Cranch to Adams 28 February 18, in this letter Cranch did not mention WT, but by this time, with Cranch serving as a commissioner briefly, they were friends.

39. WT to Blodget 23 February 1800 pp.535-7; Diary p. 218; National Intelligencer 8 December 1800.

40. Jefferson to Commrs., 2 June 1801; Commisrs to Lovering ;

41. Madison to WT 8 August 1801; WT to Madison 16 March 1801, 15 August 1801, 8 September 1801 , Madison to Jefferson 16 September 1801 Founders online; Harris pp. 560-1, 581, National Intelligencer 8 December 1800; agreement with Voss 26 June 1802. Judging by what impact he had on the newspapers at the time, the builder Nicholas Voss had at least built houses in Alexandria and one on Capitol Hill that he still owned. He sold building materials, owned many acres in Virginia, was comfortable with slavery, and in 1802 held the rank of captain in the Washington militia. There is no reason to think he would be awed by Thornton and his eventually pressing Madison to pay back rent suggests that he was not awed by the secretary of state.

42. WT to Jefferson 17 April 1802; Jefferson enclosure 14 April 1802; White to Jefferson 13 April 1802;

43. Jefferson to WT 23 April 1802: Clark, "Dr. and Mrs. Thornton" p. ; Thornton deposition, 1812 American State Papers Misc, vol.1 p. 193; Munroe to Jefferson 15 June 1802.

Comments

Post a Comment