Chapter One (1753-1785): A Tale of Two Properties, Lancashire and Tortola; and a Scientific Education

The Doctor Examined, or Why William Thornton Did Not Design the Octagon House or the Capitol

In 1753, William Thornton's father, also named William, arrived in Tortola, British Virgin Islands. Like many Quakers in Lancashire, England, west of Manchester and flanking the Irish Sea, he was brought up to be a merchant. His uncle James Birket had made a fortune based in Antigua and likely encouraged him to go to Tortola because it had a Quaker community that Birket helped found. Marriage vows in 1757 gained the emigrant Thornton plantation land and slaves that came with a Quaker wife named Dorcas Downing Zeagers whose sister was married to John Pickering, the richest man on the island and also a Quaker. On that small island, 3 miles by 12 miles, 10,000 slaves worked for and served 1,000 whites. At that time, Quakers could own slaves. William Thornton was born in May 1759.

Thornton's father died soon after his second son Absalom was born in 1760. In 1764, William and Absalom were sent to their father's Uncle Birket in England to get a Quaker education. He could fill a letter with Biblical quotes and citations, but was also a man of the world having visited America, corresponded with Benjamin Franklin about lightning, and, with his nephew Dodshon Foster, shipped slaves from Africa. He also arranged for the education of Dodshon's sons Robert and Myles. Robert was four years older than William and one might say that he paved William's way through Lancashire's Quaker schools.

|

| 7. Old Customs House in Lancaster built as Thornton grew up in and around the city |

That seemed to work to William's disadvantage because his cousin shined in ways that he couldn't. Robert's better command of Greek and Latin was the least of it. By 1775, as Birket explained in a letter to Robert, "Billy and Absy" had "not improved to my expectation." They had at least chosen their future careers: "Billy has determined to be a Physician and Absy a Merchant.”

Then cousin Robert dazzled the extended family with a brief career of fame or infamy followed by glorious redemption. He had also wanted to be a physician. Then in 1772, he went to Antigua where his father and Birket arranged for him to apprentice with a store keeper. He primarily oversaw slaves about to be sold. In 1775, he broke his agreement with his master. By breaking his agreement, he forfeited the right to be a Quaker, as did his next move. In 1776, he shipped out on a British navy brig to capture privateers from the revolting colonies who were attacking the profitable West Indian trade. He rose to the rank of lieutenant and commanded a ship.

The shock Foster gave his great uncle likely increased Birket's worries about the Thornton boys or at least William. Absy soon returned to Tortola where he met his new step-father. In 1766, their mother remarried. Her second husband signed an agreement that provided for the boys' education and half of the estate would be theirs to share once they came of age. But that husband died within a year of marriage. In 1773, she married again. Her new husband, who came from the neighboring island of St. Croix, wanted to become the boys' guardian which worried Birket because the new husband also invested in and expanded the plantation. He soon had his own son, James Birket Thomason. Still, the agreement remained. Evidently, Birket worried that while anticipating his coming wealth, Thornton might stray. In May 1777, he apprenticed William for four years to work in Dr. John Fell's apothecary shop in Ulverston, Lancashire, which Thornton would liken to slavery. His master Dr. Fell was more than a country doctor. He would become a notable exponent of electrical therapies to treat neurological diseases. The Royal Society accepted his clinical letters on that topic. But Thornton would dismiss his experience with Fell, writing in his journal on May 10, 1781, the day it ended: "This day does my four year chain drop off."

Meanwhile, Robert came back to the fold. In the fall of 1779, Lieutenant Foster returned to Lancaster. As Birket put it: "He quitted the fighting trade at his grandfather's request, and seems to be a very sensible youth." He hoped to captain a merchant ship, but then he accepted his grandfather's offer to manage a Yorkshire estate. He lived and worked with the farm hands. Humility, discipline and willingness to help others were traits prized by the Quaker community. In April 1780, he attended the Kendal Quarterly Meeting with Birket. By May 1781, he was accepted again as a Quaker. The 27 year old hardened by war who returned professing the desire to work a farm and work for and with the community moved hearts.

Once his apprenticeship ended, Thornton received his share of the profits distributed by the plantation's London agent. The rich young man had a few months to do what he wanted before matriculating at Edinburgh's medical school . He proved that he done more than mix medicines for four year. As well as devour books, he had honed his skills in drawing and watercolors and fancied that he was a poet and spent the summer with them. He also reacted to the naval exploits of his cousin. He worked on an engraving of Caesar Augustus, with "Thornton" written below in Greek. His reaction to Foster's return to the Quaker fold came soon after.(1)

|

| 8. Augustus with Thornton written in Greek |

Thornton impressed the poets. They noticed his privileged status. When the summer of '81 was but a memory and Thornton in school, the Quaker poet Thomas Wilkinson, who was eight years older than Thornton, described his vision of the future doctor: “I doubt not when I hear Dr. Thornton keeps his carriage and country house and his hours set aside every week to subscribe to the poor gratice, that I shall be ready enough to let it be known he was once my friend, for my part I believe I shall never be a greater man than I am, but I don't mind...."(2)

|

| 9. Thomas Wilkinson's cottage |

But there were limits on Thornton's freedom. Quaker discipline relies on Quaker overseers. During the ensuing winter, Thornton received a letter from Birket excoriating his behavior during the summer. In a letter to Wilkinson, Thornton quoted his great uncle:

“I was told the other day by a Friend who had been at Kendal Quarter Meeting that he had seen a Friend from Penrith side, who told him that thou hadst behaved whilst at Penrith very badly in sundry aspects, keeping but very improper company, being out at nights, and to one offered half thy estate if he would go with thee to the West Indies. These complaints have affected me exceedingly. Are these the returns thou makest me for all my care, concern and anxiety for thee, and the advice and council carefully given thee this 14 or 13 years.”

Shaken, Thornton sought the consolation of Wilkinson. “Many people endeavor to destroy the peace of others having none themselves,” Thornton wrote and then proved that he had read the epistolary novels that were the best sellers of the day. “Oh! I am hurt – I am troubled – I am afflicted beyond everything. Who could be so malevolent as tell such things to my uncle? I think any person who knows my disposition perfectly will give him a much better account.”

Thornton did not deny the allegation. Wilkinson replied promptly and did not address the allegation. He commiserated with other news Thornton bemoaned. His "kind...good...loving" brother Absalom had died in Tortola. Wilkinson urged Thornton to see his brother's death “as a visitation of mercy, a profitable admonition for us to enter and pursue the same path of virtue, that like them we may close our eyes on this world with comfort, then I trust we shall open them on our dear removed friends in the blissful kingdom of peace...."(3) Other thoughts likely crossed Thornton's mind after the death of Absalom. It doubled his fortune. If he did become a physician, he could treat everyone "gratice." Then again, did really want to be a physician?

For two years, October to May, medical students had to attend lectures in six courses: chemistry, botany, medical practice, materia medica, medical theory, and anatomy. Thornton took a shine to the sciences. Ten year after leaving the university, he sought appointment as a professor of chemistry in Philadelphia, but didn't get the job.

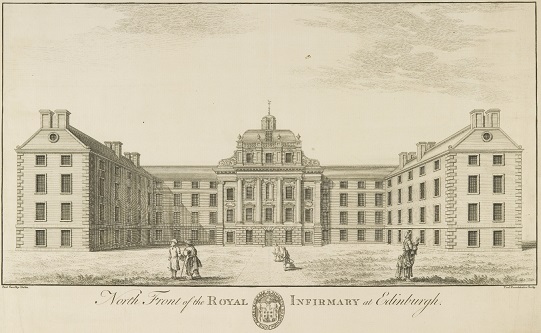

|

| 10. Medical Students became very familiar with the Edinburgh Infirmary |

He joined other students with artistic talent to create a student society in natural history. Student societies prepared M.D. candidates for writing and defending a thesis which was required to get the degree. Thornton presented a paper to the society. “On the Preservation of Birds” was all about embalming them. He also became a member of the Antiquarians of Scotland which was not limited to students. He presented the same paper to them. However, it wouldn't do as his thesis.(4)

Unlike other students, he didn't work on his thesis when classes ended. In the summer of 1782, he toured Fife with a scholar afire with poems in Gaelic. Thornton hit on the idea of a shorthand to record the unlettered bards. After he completed courses in the spring of 1783, he hobnobbed at the castles of the great men of the Antiquarian Society, head of the Clan MacDonald and the like, who soaked themselves in Scottish lore. Judging from the letters he wrote and saved in the year after he left Edinburgh, his most significance new friend was not a medical man. Sir Ludovick Grant, 6th Baronet of Dalvey, inherited the fortune and the title that his brother purchased from the king. Alexander Grant had been a doctor but then bought Jamaica sugar plantations and an island off Sierra Leone to accommodate slave traders.

In August 1783, more than two months after his classes ended, the illness and death of Thornton's great uncle brought him back to Lancaster. He arrived too late to see him, but boasted of his effort to get there in a letter to Sir Ludovick: "I was only about fifty-two hours in going from Glengairy to Lancaster which is three hundred miles, including the four hours that I slept and was on horses all the way except seventy miles. I lived chiefly on opium all the time for if I eat or drank anything it would not towards the latter part of the journey stay upon my stomach. I recovered my dreadful fatigue in three days perfectly, and have had my health very well since; my looks would indeed tell you so if you beheld me now."(5)

Birket's death made part of Wilkinson's vision a reality. Thornton inherited “properties” in Lancaster. However, Robert Foster inherited the better half of their great uncle's property. Then, Thornton proved himself the more magnanimous legatee. He signed over the income from his Lancaster properties to his grandmother and two aunts to enjoy during their lifetime. In a January 1783 letter to Foster, Birket had mentioned that he had written a long letter to Thornton. Perhaps he urged Thornton to care for the ladies. No letters Thornton wrote to his relatives at that time are extant. Years later in a letter to James Madison, he valued the property at $40,000.

In the fall of 1783, Thornton followed the well worn path Edinburgh graduates made to London hospitals and Paris clinics that put the finishing touches to a doctor's education. Thornton wrote his long letter to Sir Ludovick toward the end of his studies in London. That letter could have offered biographers a valuable report on Thornton's medical education. Instead Thornton was eager to report his prospect of marrying in Tortola and possibly increasing his fortune with more sugar plantations and slaves.

He described his joyful meeting with his stepfather in London who had come for the London social season. Thornton moved in with him and met the governor of the Virgin Island, a close friend of his step-father's. Another close friend offered the hand of his daughter to Thornton as well as a 10,000 Pound dowry. “My father's consent was asked," Thornton informed Sir Ludovick, "he freely gave it, for, from his long acquaintance with her, he knew her disposition to be one of the best. Her fortune though a very good one is not an object with me (were it indeed there are 2 in our small island of dozen times the fortune)..." Marrying in Tortola would swell his fortune with more sugar plantations and slaves. As for his medical studies, he only advised the Baron that after studying in Paris and Holland, he would finally have a chance for leisure, adding that "had I enjoyed the pleasures of the chase, and led a life free from the anxiety of acquiring learning, my constitution had been less delicate."(6)

He did form a medical friendship in London that lasted far longer than his friendship with the baron. A cousin on his mother's side of the family, John Coakley Lettsom, had established himself as the city's leading Quaker physician. He too had been born in Tortola, and then sent to England for a Quaker education. He got his M.D. at Leyden. He took an instant liking to Thornton. In a 1787 letter to another British doctor, he would extol the virtues of the “brilliant Thornton.” He also had a passion for botany and recognized Thornton as just the man to refresh what memory he had of Tortola's flora by making drawings for a book he had wanted to write, the “Flora Tortoliensis.”

|

| 12. Dr. Lettsom and Family in his Garden |

Lettsom's fame as a Quaker doctor attracted London's poor who counted on his medical care "gratice." His interest in botany attracted the famous African explorer Henry Smeathman, who had spent several years on the coast of West Africa in the 1770s. He wrote a monograph on the termites of Africa. His illustrations of termite houses delighted Enlightenment society. Lettsom was thoroughly entertained by the naturalist who brought Africa to life in ways that others didn't. Smeathman knew that a naturalist needed the help of natives. He had married daughters of two African kings.

His becoming the most prominent Quaker physician in London put him in Smeathman's sights for another reason. The explorer had entertained an offer from another famous Quaker doctor, the late Dr. John Fothergill, to raise 10,000 Pounds to finance an expedition to take unwanted blacks in London back to Africa to a live in a free colony. During the late war in America, the British government guaranteed freedom for slaves if they defected to the British side. Most were taken to Nova Scotia and then many of them taken to London. Smeathman was game but Fothergill balked at buying weapons to protect the colony.

In a brief October 1783 visit to London, Smeathman alerted Lettsom that he was planning another trip to Africa ostensibly for a trading firm interested in Africa for other reasons than exporting slaves. Lettsom introduced Thornton to Smeathman, but it wasn't until they were both in Paris that the student fell under the spell of the explorer.

Armed with a letter of introduction from Lettsom to Benjamin Franklin, Thornton reached Paris by February 1784. Lettsom introduced Thornton as “a student of medicine and a young gentleman of fortune from Tortola,” and added, “I think he will make a distinguished character; he has at present too much sail, but age will give him ballast.” He soon proved the point. (7)

14. Smeathman's Drawing of Termite Hills

14. Smeathman's Drawing of Termite Hills

The ever popular and comely young man of medium height and around 160 pounds, struck the fancy of the Comtesse de Beauharnais, who hosted a salon. She was almost 50 years old and unhappily married. She wrote a poem about him; he painted her portrait; her letters would so shock the future Mrs. Thornton that she burned them. She recalled years latter that "the adoration” the comtesse “expressed amounted almost to impiety."(8) Thornton didn't neglect Frankin's salon where he found Smeathman and the French geologist Barthelemy Faujas de Saint-Fond, famous for his theory on the origin of volcanoes.

What Smeathman wrote to Lettsom is extant, but not what Thornton might have written. Both saw the Montgolfier brothers' balloons. Smeathman sent his design of a better flying machine to Lettsom and asked him to forward it to the Royal Society so Britain would never fall behind the French in that regard. Thornton wrote "On Balloons" but didn't send it to anyone. Evidently Smeathman got no money for his African plans but trusted if his balloon didn't raise the money, then English Quakers would. Thornton loaned him money to pay his passage back to England.

Thornton also lent Faujas money, and joined his natural history tour of England, Scotland and the Hebrides. Thornton was back in London by mid-August. With Faujas, Thornton met the President of the Royal Society Sir Joseph Banks, and famous astronomer Herschel. With Thornton, Faujas dined with Lettsom. Then, Faujas and Thornton were joined by an Italian count, a continental medical expert on syphilis, and James Smithson, a young man who would later endow the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. It is not certain if he saw Smeathman, but Lettsom could have updated him on the latest. Still in Paris, in a July 16, 1784, letter to Lettsom, he outlined his ideas for a republic of freed slaves sent back to Africa with a guarantee of favorable trade relations with Britain. Smeathman added: "Dr. Franklin tells me he has no doubt that I should get it adopted at Boston; but, alas! I cannot carry my poor brat a-begging from continent to continent on uncertainties."

In the memoir of his scientific exploration of Britain, Faujas lauded "William Thornton, whose eye is as penetrating as his judgment, exclaimed: 'what you tell us appears to me so true, that I think I see at a little distance, some discolored lavas, which may very probably present to us the remains of an ancient crater.'" When the others flagged on the way up an ancient volcanic mountain, Thornton made it to the top. He also had local knowledge. In Newcastle, he had a good friend who was not only an enthusiast for nature and art, but also provided “opportunities to examine mines and several manufactories.” Most exciting to Thornton was Faujas' discovery of poussolane deposits which could be used in making cement. Thornton contemplated commercial mining with Faujas and the expert on syphilis.(9)

The tour ended in October. Thornton did not go back to Paris. Not only had he not completed his thesis but he lacked one course, botany, to satisfy his degree requirements. He returned to Edinburgh to save the day. He enlisted the help of the Natural History professor. Dr. John Walker, who was a clergyman not a physician, had become a good friend. The University of Aberdeen did not have a thesis requirement for M.D.s. Walker wrote to Aberdeen extolling Thornton. He had satisfied all the lecture requirements at Edinburgh except botany. He could not do that because he had to return home to the West Indies. There was no mention of his thesis. Aberdeen awarded him the degree. Evidently, Thornton did not even have to make an appearance.(10)

Thus ended Thornton's European education. The Quaker lad from Lancashire connected with Scottish and French nobility, won the admiration of at least one professor, a world famous geologist and Dr. Lettsom. He left a good impression everywhere. In 1795, Lettsom would write to George Washington and extol Thornton as a man with "a heart—an openness, a candour, and an ingenuous disposition; that, I think, are more amiably combined in his character, than in any I ever knew." Those were kind words, but he called Thornton "ingenuous" which Samuel Johnson defined as "open, fair, candid, generous, noble." He didn't describe him as ingenious, which Johnson defined as "witty, inventive, possessed of genius." In a letter of introduction to Franklin, Lettsom described Smeathman as "ingenious."(11)

To prepare for his return to Tortola, Thornton went to Lancaster in March 1785 to say his goodbyes. He also finally replied to a letter Wilkinson had sent in August. His reply made one thing evident. Other than returning to Tortola for a visit, Thornton still did not know what he was going to do for the rest of his life. In 1821, he would badger his friends Thomas Jefferson and James Madison to support his aspirations to be sent on a diplomatic mission to South America where revolutions convulsed Spain's colonies. He claimed that he had been a revolutionary since his Edinburgh days. To Jefferson, he added that the Comtesse had tried, through a Bourbon noble in the French government, to win Thornton the right to apply the education he had received by touring with Faujas by touring Mexico.

In his March letter to Williamson, he didn't mention Faujas and hadn't dreamed up his Mexican fantasy. He also didn't mention Smeathman and Africa. With the excitement of London, Paris and Faujas behind him, his letter mainly addressed the momentary problems of mutual friends who were poets. He joked about Isaac "because I'm afraid the dose of opium I gave him last night will lay him in eternal rest." Then he made some light self criticism: “My letters are, to be sure, well filled in general, but thats all. I give in quantity what other sober thinking folks can give in very little room in quality.”(12)

His conversation had that same characteristic. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams and his wife lived next door to Thornton from 1820 to 1825. In a November 22, 1820, letter to her father-in-law, Louisa Adams wrote: “Dr. Thornton called in late last Evening and chatted some time. His conversation is indeed a thing of threads and patches certainly amusing from its perpetual variety—He is altogether the most excentric being I ever met with possessing the extremes of literary information and the levity and trifling of the extreme of folly—He is good natured rather than well principled."

Louisa Adams was not a narrow minded New Englander. She had been born and raised in London where her father had been the American consul. She evaluated Thornton by London standards. Juxtaposing Thornton's confession in his 1785 letter to Wilkinson with her observation made 35 years later gives some context for Thornton's sudden transformations throughout his life. His mind played with the surface of things. He was too vain an opportunist to anchor his rhetorical flourishes in the profound. He had too much sail and never found his ballast.(13)

Wilkinson had walked off to London to attend the Quaker Yearly Meeting and there found a revolution, a cause for the rest of his life: “the almost naked and prostrate negro, at many a corner. At first glance we hardly conceive it to be a human being.” If he had money, he wrote in his diary, he would build an asylum for “the old or disabled negro.” At the Yearly Meeting, he bonded with Quakers from Philadelphia. The delegation included not just the usual merchants rich enough to make the voyage, but also two ecstatic women who were afire with the cause of ending the slave trade, a sin that Americans blamed on the British. Thornton returned to London before sailing to Tortola. He bumped into Wilkinson who was still pulsing with the anti-slavery testimony he had heard at the Yearly Meeting. Wilkinson wrote in his diary that he was gratified to hear Thornton's warm opposition to the slave trade, and that he "was meditating a scheme for its abolition, but I thought the means proposed too weak for the magnitude of the object."(14)

It is not known what his scheme might have been. He had lately been exposed to two relevant ideas, what Lettsom had done and what Smeathman planned to do. Upon

the death of his father, Lettsom, then 23 years old, had returned to

the island, took control of his inheritance, and freed his slaves. He

absorbed that loss of 500 Pounds by practicing medicine on the island.

He made 2000 Pounds in six months, gave half to his mother and returned

to London with ample funds to start his practice there, and thus ended

any association with or dependence on slaves.(15) However, in 1783, Lettsom

was not an unabashed abolitionist. He patronized activists working

against the slave trade, but he had learned to regret rashly freeing his

slaves and had come to believe that blacks had to be prepared for

freedom, with one exception. They could be returned to Africa by Smeathman.

Thornton left the Old World and never returned. He never saw Wilkinson, Dr. Walker, Sir Ludovick, Dr. Lettsom, Smeathman, Faujas, the Comtesse, as well as his English relatives including Robert Foster again. None of them had any reason or inclination to go to Tortola or America. Franklin returned to Philadelphia.

Go to Chapter Two

Footnotes to Chapter One

1. Jenkins, Charles F., Tortola: A Quaker Experiment of Long Ago in the Tropics. Friends Bookshop, London, 1923 pp. 23, 58; Correspondence of James Birket; Harris, Papers of William Thornton, pp. xxxiv-xxxvi; an on-line biography provides the same material, Paulson pp. 7 - 11; Beck, Ben, Foster Family Webpage. Franklin to James Birkett 1 March 1755.

2. Kelliher, Hilton, "Thomas Wilkinson of Yanwath, Friend of Wordsworth and Coleridge" p. 149; Papers of William Thornton, p. 1, Wilkinson to WT, 22 November 1781

3.Papers of William Thornton,WT to Wilkinson 5 March 1782; Wilkinson to WT, 13 March 1782.

4. Bell, Winfield, “Philadelphia Medical Students in Europe 1750-1800, Penn. Mag. Of Hist. And Bio, Jan ;1943, pp. 9, 10; Papers of William Thornton , WT to Benjamin Rush, 11 September 1793.

5. Papers of William Thornton,WT to Grant, December 1783; Harris p. 21; Legacies of British Slavery, "Sir Alexander Grant" ; Jenkins, pp. 47-50;

6. WT to Grant, December 1783; Harris, p. 13 Papers of William Thornton; WT to Madison, 2 September 1823;

7. Pettigrew, A Eulogy on John Coakley Lettsom, 1816 (Google Books) pp. 5; Lettsom to WT, 5 March 1796; on WT in London, Harris p. xxxix; Allen Clark, "Doctor and Mrs. Thornton," p. 147 (JSTOR); on Lettsom, Jenkins p. 48, Woodruff, A.W., "Lettsom and his Family in Tortola," 7 June 1972; Paper of William Thornton, Lettsom to WT 25 July 1792; Jenkins, pp. 48, 60; Coleman, Deidre, Henry Smeathman, the Flycatcher. Liverpool University Press, 2018, p. 24; Pettigrew vol. 2, Smeathman to Lettsom, 16 July 1784, in Pettigrew vol. 2, pp. 268ff; Pettigrew was the source for the letters collected by Harris. JCL to Franklin, 28 Jan. 1784:

8. Harris, p. xl; "Mrs. Thornton's Diary", p. 144; on size see 7 May 1808, Washington Federalist p. 3.

9. Faujas, B., Travels in the Hebrides and England,p. 134 (Google Books); WT to Swediaur November 1784, Harris, p. 17; 20; Harris, p. xl

10. WT and Walker, Harris pp. xxxvii-xxxviii.

11. Lettsom to GW, 15 July 1795; Lettsom to Franklin, 2 August 1783.

12. Carr, Mary, Thomas Wilkinson: A Friend of Wordsworth, p. 8, 9; WT to Jefferson, 9 January 1821. In his later years Thornton had a tendency to exaggerate.

13. Harris, p. 20; Louisa Adams to John Adams, 22 November 1820.

14. quote from Wilkinson diary, Harris p. 29 footnote.

15. Jenkins p. 53.

Comments

Post a Comment