Chapter Seven: Thornton v. Hadfield

The Doctor Examined, or Why William Thornton Did Not Design the Octagon House or the Capitol

Chapter Seven: Thornton v. Hadfield

|

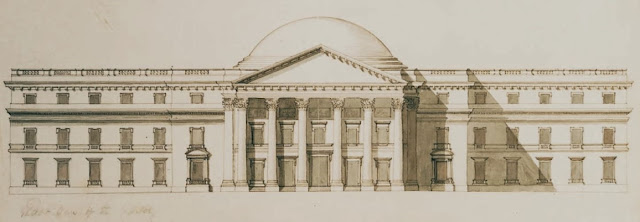

| 84. Hadfield's simplification of the 1793 Conference Plan |

Hoban would recall that when Hadfield took over, the North Wing's walls were "two or three feet above the foundation wall."(1) When Hadfield signed his employment contract on October 15, he "requested permission in the presence of the full board" to give them his opinion "respecting the state of the building, after having procured the designs and examined the work." Then in his October 27 report to the board, Hadfield began by belittling the plans he had been shown: "I find the building begun but do not find the necessary Plans to carry on a work of this importance, and I think there are defects that are not warrantable, in most of the branches that constitute the profession of an Architect, Stability - Economy - Convenience - Beauty...." He criticized the interior for “material inconveniences in the apartments, deformity in Rooms, chimneys and windows placed without simmetry, and no oeconomy of space.” Then, in a second letter, he assured the board that he would do his best to “adapt to the best of my abilitys those parts that are already executed, without alteration.”

|

| Wanstead House |

The president's reference to the dome had to stun Thornton. He had not mentioned it in his letter, but the president had evidently talked about it with Hadfield. Allusions to the dome covering the "open" area meant that Hallet's court yard of some sort still lurked in the president's imagination. Then while the president put Hadfield in his place, he also insulted Thornton by not crediting him for the design of the Capitol.

A personal letter he wrote to Thornton on the same day all but said that he approved Hadfield's plan solely on the basis of his character as an architect: “If [Hadfield] is the man of science he is represented to be, and merits the character he brings; if his proposed alterations can be accomplished without enhancing the expence or involving delay; if he will oblige himself to carry on the building to its final completion; and if he has exhibited any specimens of being a man of industry and arrangement I should have no hesitation in giving it as my opinion that his plan ought to be adopted....” George Washington had never and would never suggest that in regards to any decision about the Capitol that Thornton's character as an architect was at stake. He thanked Thornton for "the explanations & details" in his letters, and added a warning about his attacks on Hadfield: "if there be any cause to suspect him of ignorance—or misrepresentation much caution, & strict investigation ought to be used." The president did not mention Hoban in either letter. What Hoban may have written about the dispute at the time or later is no longer extant. But judging from what the president wrote to the commissioners, Hoban did not own up to lamenting and correcting anything with Thornton. There is no evidence, other than his say so, that Thornton did indeed collaborate with Hoban in correcting defects in the foundation after that season's work had to be torn down.(7)

The president left the decision up to the commissioners because "I have not the precise knowledge of the characters you have to deal as well as all the facts in the matter." In a letter signed by all three, the board cited a cost estimate by Blagden that Hadfield's design would be more expensive. They also cited the expert opinions of Hoban and Thornton that Hadfield's building would be unstable. His colleagues allowed Thornton to make the case that Hadfield wasn't needed without making a formal dissent to the president. In their letter to the president, they enclosed a November 17 letter Thornton wrote to the board giving "assurances" that the job could be done without Hadfield: "I promise to supply such drawings hereafter, as may be deemed sufficient for the prosecution of the Capitol, and in time to prevent any delay whatever." Thornton added that he was "authorized by Mr. Hoban to say that if Mr. Hadfield declines the superintendence of the building on the present plan, that he will engage to undertake it, and proceed with it to a finish." Thornton shifted from discounting the need for drawings to promising to provide all the drawings needed himself. What likely caused such an about face was the president's writing that "the present plan is no body's, but a compound of every body's." Without directly contradicting the president, Thornton notified his colleagues and the president that he could fulfill the design contest winner's obligation to provide drawings as needed. The president did not reply to the board's letter or show any appreciation for Thornton's offer. He had his secretary write that he approved of their "proceedings."(8)

The president's letter might seem like a decisive take down of Thornton's pretensions. However, for the city's first comprehensive historian, Wilhelmus Bogart Bryan, whose History of the National Capital was published in 1914, Thornton's November 17 letter to the commissioners was evidence proving that Glenn Brown, his colleague in the recently organized Columbia Historical Society, was right: Thornton did restore his design of the Capitol. Bryan did note what the president said about the design but suggested that in "Washington's mind, at that time, at any rate, the authorship of the design was doubtful." Working drawings are rarely preserved, so Bryan assumed that Thornton, as he promised, began to supply drawings and through that process dispelled the president's doubts about who designed the Capitol.(9)

Hadfield would not be fired until May 1798 and in the meantime he would build the North Wing save for a portion of its roof. In all that time, the president did not credit Thornton for anything to do with the design of the Capitol, not even after he left office in March 1797 and Thornton became a frequent visitor to Mount Vernon. The only comfort Thornton had was that nobody credited Hadfield for the design and that he continued to think the design laughable. That left a vacuum which a brilliant architect could fill with a triumphant narrative. Until 1808, Thornton tried to do that. He began stretching the truth in January 1796. In June 1798, he began to tell himself lies.

In the draft of the never sent letter to the secretary of state, he claimed that in 1795 even with design already set, he helped Hadfield. The upstart had complained to the board that he "could do nothing without sections being made of the whole building, although one wing only was to be executed." Thornton recalled that he knew sections "to be unnecessary," and Hadfield's request "only intended by him to fatigue me by throwing difficulties in my way. These I stated, but by the Board attending to his representations I was under the necessity of complying with their wish to satisfy him. I drew the section of the whole accordingly."(10)

More likely, he didn't draw the section which, since he had assured the president that no changes had been made in Hallet's interior, would have been a section of Hallet's plan. Also, in the documents generated by the board from November 17 to December 3, 1795, when commissioners White left for a six month mission to lobby congress for money, there is no mention of Thornton being asked to make drawings. For the board to have ordered him to do so with White gone, Thornton would have had to have joined Scott to make the order

Thornton corresponded with White and mentioned drawings and promised more, but he likely didn't draw anything for Hadfield. Their correspondence began in a way that embarrassed both gentlemen. White was the commissioner who knew the least about the Capitol. As

White left for Philadelphia, he asked Hadfield to send a plan of the

Capitol with the estimated cost and Hadfield sent his own plan. White

shocked Thornton by reporting that a congressional committee asked for a

copy of the plan for the Capitol, and he showed them Hadfield's.

Thornton immediately sent up what he described as a "roll of papers" so

the committee could see the "plans formerly adopted by the President, and now in progress...." The mail came but White did not get the plans. He informed Thornton that they had apparently been lost.

In a draft of a letter to White written on January 16, Thornton seemed at once to think the worst and shrug it off. He regretted that Hadfield's drawing was exhibited but noted "in fact it is not indispensably requisite to show the plans exactly as they are meant to be." Then Thornton revealed his dark fears of machinations "by one who does not wish well to my plans, or to anything that comes to me, and who, I believe, has urged Hadfield further than he intended to go." Thornton was probably thinking of Thomas Johnson who led the first board that first questioned Thornton's design, had alerted his brother in London about the need for an architect, and continued to stalk the city protecting his investments.

In the same letter, Thornton reiterated how he was putting Hadfield in his place. "Since your departure I have been occasionally engaged in making correct drawings for the Superintendent of the Capitol in which it will be impossible to make any mistake. In this I have paid great attention even to the minutiae, lest difficulties might be made where in reality none ever existed." The occasion could not have been dictated by progress on the building because apart from cutting stone no work was being done in the winter. On December 29, Hadfield was told to account for all the building materials at the Capitol and "lay before the board the materials which will probably be wanting for the next year supposing the business to be carried on with vigor." It is possible that Hadfield asked Thornton for drawings of minutiae so that he could decide what was needed. However, the board's order did not offer that help, and the board's secretary, not the board members, signed the order.

White found that the "roll of papers" had been sent to the War Office. In his letter to Thornton, he described them as "your plans." That raises the question: Had Thornton made his prize winning design the operable plan? But in the same letter, White referred to the plan ''adopted by the president" which was the phrase his colleagues used when warning Thornton not to make any changes. The roll probably contained copies of some of what Hoban took to Philadelphia in November. In a February letter to White, Thornton promised to send other drawings to White and assured him "I have taken great pains with them and I hope I shall have no further trouble." There is no evidence that he sent drawings. In a letter to a newspaper published in 1819, Hadfield recalled that in regards to the design of the exterior of the North Wing, his providing "the finishing the practical working drawings of all the cornices, and other parts of the exterior of the North Wing from the plinth to the top of the ballustrades,... was doing no more than I was obliged to execute, as superintendant of the building." Thornton did not contradict Hadfield's claim.(11)

It took six months of lobbying for White to get a loan guarantee through congress. Until then, despite Thornton claiming to have made drawings to forward the work, Scott and Thornton delayed the usual spring resumption of work on the buildings. In mid-May, White returned to the city. Appalled that work had not resumed, he got the board to rally proprietors to loan money to pay workers and suppliers.(12)

The president was already thinking hard on commissioners Thornton and Scott for other reasons. They had still not moved into the city. In a May22 letter, the president chided them for living too far from the Capitol to properly inspect its construction:

The year 1800 is approaching by hasty strides; The friends of the City are extremely anxious to see the public Works keep equal pace therewith. They are anxious too on another account—namely—that the Commissioners should reside in the City where the theatre of the business lies. This was, and is, my opinion. It is the principle, and was declared to be so at the time; upon which the present establishment of the Commissioners was formed; that, by being on the spot, and giving close attention to the operations, they might prevent abuses, or correct them in embryo. It is said, if this had been the case, those defective walls, which to put up, & pull down, have cost the public much time, labour & expence, would never have been a subject of reproach.

Scott’s and Thornton’s reply was flippant:

It is not unknown to us that some unthinking persons have attributed the mal-construction of the foundation-Wall of the Capitol to the want of attention on the part of the Commissioners—but if they had visited and walked over the Walls three times a day, it would not have been possible to prevent imposition where men are resolved to practice it, and the Commissioners had reliance on the Work, not only from the Character the undertaker then enjoyed; but also on the care and attention of the Superintendant—Many disadvantages are attributed to the non-residence of the Comms. in the City—We lament that any person could expect us to live there, before houses are prepared for accommodation—some of the board have always said, that they mean to remove thither as soon as even decent houses could be had—The proprietors have not been active in their preparations, otherwise, this cause of their complaint would not now exist."(13)

Having been in Philadelphia for 6 months, White had been excused from moving, but he agreed to try to arrange his affairs so he could move. Scott wrote a personal letter to the president, now lost, defending himself. Thornton seemed to live in a dream world. In a November 26, 1795, letter just after the president didn't recognize him as author of the Capitol design, he wrote to Lettsom about how close he was to the president. He had bought lots "next to those whereupon the President means to build his private house of residence in the city, which we have travelled over together on foot and laid out our plans of future improvement.... We were alone, and I thought myself highly favored by the manner in which this great man received my opinions." On June 5, the president wrote to Commissioner White that his asking his colleagues to move to city "is not at all pleasing to Mr Scott. How it may be to Doctor Thornton I know not, having heard nothing from him on the Subject."(14) Evidently, Thornton had put himself in Blodget's shoes. In 1793, the then superintendent and the president had walked over his lots and discussed his plans.

On June 13, 1796, the president left Philadelphia for Mount Vernon and didn't return until August 17. That promised more oversight of the commissioners. On June 19, he was in Georgetown and paid $1,294 in cash to cover what he owed for lots he had bought in the city. On June 22, he began sending letters from Mount Vernon to his cabinet secretaries. On June 24, Hadfield gave the board three months notice.(15) In the draft of the 1798 letter he never sent, Thornton claimed that Hadfield left because the president rejected another design that he drew:

His next idea was that as the building could not be reduced from from three to two stories it had better be changed to four stories. The President and Mr. Johnson were both here. They heard of these attempts so incongruous in themselves, with astonishment. The President determined that no alteration should take place, on which Mr. Hadfield resigned his office as Superintendent of the Capitol. The Board accepted his resignation.

However, the letter the board wrote to Hadfield did not mention another design or the president. The letter gives the impression that Hadfield was unhappy with his "situation" at the Capitol. Rather than wait three months, the board wanted to release him from that situation as soon as possible for fear that the "people" there would no longer follow his commands:

The

board have had your notice of the 24th Inst. under consideration, &

also the conversation which past at the board; and supposing your

present situation at the Capitol to be an unpleasant one, they feel

every disposition to relieve you from it—As you are to quit the Capitol

at the end of 3 months, & this fact is well known among the people;

we Suspect it will be difficult to keep up due authority among them; and

that it will be best for both the public and yourself that you should

be relieved from your present situation immediately; and that the board

should pay your passage to England, or thirty five Guineas, in lieu

thereof, instead of paying you three months Salary.

That suggests that Hadfield had problems with workers at the Capitol, not with the board and the president who were rarely at the Capitol. Many of those Irish workers had been working for Hoban at the President's house and moved to the Capitol.

In a June 29 letter to the president, after discussing three other issues, the board reported their "surprise" at Hadfield giving notice and that they gave him "liberty to quit" and passage money to England. Then "he seems to have considered the subject better & has applied to withdraw his notice, promising every attention to carrying on the Capitol, as approved of by the President—."

In his 1798 recollection, Thornton fancied that he extracted a confession from Hadfield:

After he returned, acknowledged he had been hasty, requested to be admitted to the public service, acknowledged he had behaved to W.T. with great impropriety - that he had made objections to the plan and section when prompted by ambition to substitute his own, that he lamented such conduct, and though he had declared the plan not executable yet he assured the Board that it was and he would faithfully execute it, and at all times advise with W.T. - He was replaced [rehired] by unanimous consent of the Board.

Thornton never sent the letter. There is no evidence backing up his recollection. There is no evidence of the president's being astonished by another design. No letter giving Hadfield's version of events in the summer of 1796 has survived.(16)

During the first crisis with Hadfield, Thornton wrote a personal letter to the president giving his version of events. During the second crisis with Hadfield, he didn't. The likely reason is that he realized that the president was more displeased with him than he was with Hadfield. In his reaction to the board's extracting Hadfield's promise to build according to a design approved by the president, the president didn't comment on Hadfield or the plan. He applauded "their decisive manner.... Coaxing a man to stay in office - or to do his duty while he is in it, is not the way to accomplish the object." However, the commissioners made it clear that they had not coaxed Hadfield. In his letter, the president was alluding to his experience with them. In his June 26 letter to them, the president had once again tried to coax them to live in the city: "It cannot be tolerated, that the Superintendant, and others, whose duty it is to see that every thing moves harmoniously as well as œeconomically; and who to effect these ought always to be on the spot, to receive applications & to provide instantaneously for wants, should be at the distance of thre⟨e⟩ miles from the active scenes of their employments."(17)

The president's observation that dismissal was a better option than the futility of coaxing men to do their duty seemed to have made an impression on Thornton. On July 18, a newspaper notice signed by Thornton announced the auction sale of his Georgetown house on August 4 and also announced "Immediate possession will be given as the proprietor is removing to the city of Washington."(18) He did not sell the house in August.

Of course, still living three miles away from the Capitol, did not prevent Thornton, from keeping a closer watch on the work at the Capitol and advising Hadfield when questions arose. But there is no evidence that he did. How else explain an October 24, 1796, letter George Blagden wrote to the board expressing bewilderment. He asked "shall the Pilasters diminish, how much and w[h]ere shall that determination commence. There being to be two modes to finishing between the said Pilasters a drawing for each will be necessary, commencing with the top of the Subb Plinth and ending at the top of Capitals." Blagden also wanted a drawing of the "entablature," which is to say the layer of stone above the order defining ornaments on the upper end of a pilaster or column. An undated drawing in Thornton's papers of a capital suggests that he was capable of obliging. But during an ensuing controversy, Thornton tried to make his point by showing his colleagues Blagden's drawing of the entablature.(19)

That said, a few months later Thornton did butt in and vex Hadfield by ordering him to liven the look of the Capitol’s outer walls with what Hadfield would call “galosh” ornaments. The inspiration for adding those features to better distinguish the rusticated stone of the basement from the finished stone of the first floor was the availability of unemployed stone carvers in Philadelphia, thanks to the bankruptcy of Robert Morris forcing work to stop on his mansion designed by L'Enfant. Thornton evidently persuaded his colleague to add some ornaments to pilasters and cornices. The board ordered Hadfield to get those carvers and he asked for help from Thomas Law who was going to Philadelphia. Hadfield was against the ornaments but explained to Law: "I am therefore obliged for the sake of peace & harmony to have recourse to the only expedient to prevent delay, by multiplying hands if possible.” He added that "the unnecessary ornements introdus’d have lost, do & will lose much time &c:" When in Philadelphia, Law told the president that $10,000 could be saved by telling Hadfield "to avoid all superfluous & useless ornaments.” In a p.s. to a February 20 letter to the board, the president reacted: "I am informed that Mr Hadfield is enquiring, in this City, for Carvers. I earnestly recommend, that all carving not absolutely necessary to preserve consistency, may be avoided; as well to save time and expence, as because I believe it is not so much the taste now as formerly." To Hadfield's delight, work continued according to a drawing he made that had no ornaments.

Thornton might seem to have been the logical person to keep the president informed about the Capitol with reassuring inside information. Instead, Thomas Law did and Hadfield was his source of information. Along with the commissioners' plan to waste money on ornaments, Law also reported that Hadfield told him that he could put the roof on the Capitol in the summer of 1797, but the commissioners forced him to delay.(20) The president began insisting and ever reminding the commissioners to finish the North Wing first.

Meanwhile, on September 19, 1796, the president decided against a third term in office and published his Farewell Address. He then asked the commissioners to bring matters "relative to the business of the City" that needed his attention. There were many things in that regard that General Washington had best do rather than any successor. By January 31, the commissioners had written out a description of the seventeen public appropriations in the L’Enfant Plan. Since March 28, 1791, technically two trustees in Georgetown held title to all the land in the city. With the president's and their signatures on the document, the government would get title to the land it designated as belonging to the public thus allowing the original proprietors to get $66 an acre for land taken from them.(21) As a corollary to that process, the design of and site for the Executive Offices to house the departments and State and War had to be decided. The president wanted to designate a site for the National University. The commissioners wanted sites designated for foreign embassies. Needless to add, some proprietors objected to not enough of their land being taken.

Thornton shined from the get go. The old board had assumed that the National University would be on land offered by Blodget between I and P Streets North and 11th and 5th Streets West. Scott and White were disposed to recommend the same to the president. However, Thornton discovered that 5 or 6 acres in that parcel belonged to minors or had been sold to "strangers." He suggested a site on Peter's Hill already designated for government use, around which both he and the president owned lots. Both his colleagues and the president agreed. The board drafted a resolution for congress to pass, and the president signed off on it, only to have congress table it in December.

Thornton dissented from his colleagues' other decisions. They recommended that embassies be built along the Mall just as L'Enfant planned. Thornton thought they should be on both sides of the park south of the President's house. As for Mall, Thornton assured the president that there the government would "build at public expense a mansion house for each representative in both houses of Congress in a similar style by which all improper competition in point of grandeur will be avoided;..." The president opposed embassies on the Mall, and in a meeting with the president, Scott got the impression that he was not adverse to embassies south of the President's house. Within a week, the board divided one of the squares in questions and Scott bought the largest lot in it. However, the president showed no interest in Thornton's idea to build a politicians' ghetto along the Mall.

Thornton and his colleagues differed over the Executive Office buildings. The board asked Hadfield and Hoban to each submit a relatively plain design for two buildings. Since they were both salaried employees that saved the commissioners from having to pay them for a design. They chose Hadfield's and Scott and White recommended that the offices flank the President's house. Thornton wanted them north of the President's house because a stone building like the President's house should not have brick buildings nearby: "to place brick buildings (though ornamented with free stone) as wings in any way connected with a stone edifice would not only be novel, but irregular and improper."(22)

Instead, his study of the L'Enfant Plan gave him other ideas. Before the president signed the finalized plan, Thornton tried to expand public grounds. He studied all the large intersections created by angling avenues crossing the grid of streets. Many of those intersections created space that dwarfed the need to accommodate traffic. He described each one and calculated the area and how much buying each plot would cost the government. For example: "No. 10 At the junction of Kentucky with the intersection of North Carolina and Massachusetts Avenue admitting a street of 100 feet in front of the surrounding squares will leave an area or parallelogram of 686 1/2 feet by 191 1/2 feet containing 131,465 square feet." A map accompanied the list. He added that "these areas will serve for fountains, obelisks, statues, temples, etc. etc. - or will be amply sufficient for handsome churches, public academies, etc. - and most of them ornamented with grass-plots, gravel walks, trees, etc." The president liked the idea. Taking that land for public use meant the grumbling original landowners would get $66 an acre for the land taken.(23)

Ironically, the future great architect became a city planner just when, in the wake of Greenleaf's failure, house building resumed and a few were actually occupied by notable men. Since it was in his job description, Thornton did deal with developers. While he was in Philadelphia, Commissioner White cultivated Joseph Cooke who had built a row of houses in that city and wanted to do the same near the Capitol. Thornton wrote that he agreed with White that "we must accommodate every person as well as we can." Then Thornton bristled at what Cooke built in Philadelphia: "...it is indeed the finest cook's shop I ever saw, but destitute of taste, and loaded with trifles, finery and whimwhams." In the same draft, Thornton bemoaned congressional critiques of the plan for the Capitol: "It would be destruction to alter a stone!" The board, formed by Thornton and Scott, offered Cooke lots at 12 cents a foot "if he really means to improve and soon." Cooke never built in the city.(24)

It is possible that speculators and developers didn't understand that Thornton was an architect. Greenleaf responded to the dismissal of Hallet by getting him reinstated. He didn't seem to know about the winner of the design contest. Of course, he hardly knew Thornton. Morris and Nicholson worked Commissioners Thornton and Scott to their advantage and got the board's help as they created a bubble, banking on their 6 million acres and city lots eventually funding their debts and raising property values everywhere as well. Scott and two associates plunged and wound up owing the commissioners $33,000. As for Thornton, before the bubble burst, Nicholson wrote to Morris that he “made a strong attack on him to get his paper." Thornton parried by saying "his wife and mother-in-law would be alarmed.”(25) There is no evidence that they talked about architecture. Thornton didn't seem to have any interest in what they were building

Lovering did. Thornton was a critic of developers. Lovering was a catalyst. To fulfill an obligation made by Greenleaf in September 1793, the speculators had to build 20 houses on lots owned by Daniel Carroll of Duddington or forfeit the lots and pay a $10,000 penalty. By the spring of 1796, no houses had been built nor any planned. Morris was inclined to renegotiate the contract with Carroll. Lovering, who had been sued by Carroll, went to Philadelphia and warned Morris and Nicholson that Carroll had "a most rigid disposition and will be glad to take any advantage." The speculators knew that they had to do something to save their investment. Building houses would raise lot values throughout the city, especially if done with eclat. Beating Carroll's deadline would catch everyone's attention. Vowing that “Mr. Carroll shall not have the forfeiture,” Morris and Nicholson promised money.

If the houses were only two stories and most shared party walls, Lovering thought they could be built by September. Morris told him that they "must be easy and cheap to execute and at the same time agreeable to purchasers and tenants." Lovering did just that and designed houses at the end of the block with storefront windows. While the designs for the houses have not been found, letters between Morris, Nicholson, Cranch, Lovering and William Prentiss, an English storekeeper who Nicholson hired as his builder, all mention Lovering's designs. Lovering described his drawings as "most suitable and economize as much as possible." Building began in late June 1796 on the square northwest of the intersection of South Capitol and N Streets SW. Despite Lovering being prostrated with a fever, his and Prentiss's crews beat the deadline. Both Morris and Nicholson came to the city and hosted a barbecue for 200 to celebrate the accomplishment. Initially, even Carroll was satisfied.

Architectural historian Pamela Scott is underwhelmed, but in her architectural history of Capitol Hill does rate one house as interesting. Their seeming success enabled Morris to sell a corner lot to a merchant named Edward Langley. The contract for the sale had the proviso that Langley have his builders "conform to Lovering's design." This proviso was likely made and enforced to help the speculators if Carroll sued. Langley had the house/store built and then in 1798 tried to sell it. To advertise the sale, a surveyor brought to the city by Nicholson, drew the building and its floor plan. In small print in the lower right hand corner of the advertisement, the surveyor wrote "Drawn by Nich. King July 14, 1798." Pamela Scott and other historians give King credit for designing the house. Scott rated the building as representing "the quality of houses and shops Carroll sought when he first contracted with Greenleaf."(26)

While Lovering was busy, so was Hallet. He began dividing his time between Philadelphia in the winter and the federal city in the summer. In the winter of 1796, Martha Washington's most celebrated grand daughter married Thomas Law. He began his building program at the river side foot of New Jersey Avenue with plans to build houses up the hill to the Capitol. There is evidence in Law's papers that he employed Hallet as a contractor through 1797. The other Nabob, William Duncanson, built The Maples, a country manor tucked in the slope southeast of the Capitol near 6th and D Streets SE. In the fall of 1796, Duncanson entertained the British minister and his lady there. Architectural historians credit William Lovering for designing the house, but in a lawsuit on another matter, Lovering testified that to help Duncanson hurry construction of the house, he provided seasoned building materials and measured the work. Lovering didn't testify that he was paid for designing or building the house. Given his detailed description of The Maples in a report for European investors, Hallet most likely designed the house.(27)

What career Hallet had afterwards was made in Philadelphia and New York. Lovering almost followed him. Morris soon took a circuitous route back to Philadelphia to avoid creditors. Nicholson gamely maintained his headquarters in Hoban's "Little Hotel" on 14th Street NW and aimed to develop lots throughout the city but creditors began calling and he made his castle in a room in a hotel he financed near the Capitol. The sheriff recognized that room as where he could not be served writs. On New Year's day 1797, Lovering who had not been paid and was being sued because of Nicholson’s bounced checks, pushed a pleading letter under the door of his room in Tunnicliff's hotel: "I conceive myself of so little use or consequence that must hardly be worth your notice.... It will be impossible for me to continue in this City with such perturbations of mind and embarrassed circumstances." Nicholson promptly gave Lovering $45. Then he paid Lovering $5 a day when he marked trees for lumber. When, Lovering's ill wife died on January 16, Nicholson loaned his carriage for the ride to Rock Creek cemetery. Nicholson was not a sentimental man. In a letter to Morris, his reaction to her death was that now Lovering would get back to finishing the houses on South Capitol Street. On February 4, creditors lured Nicholson out of his castle and he was briefly jailed in Georgetown but enough men loath to see the bubble collapse paid his bail. Shortly after that, without giving anyone notice, Nicholson returned to Philadelphia. Lovering followed him and saw Morris too. He wrote back to Cranch: "they are at wits end almost."(28)

|

As it turned out, Thornton could not sell his Georgetown house. Perhaps, that prevented him from designing and building a house for himself. It cannot fairly be said that he turned his back on architecture. The board of a church in Georgetown asked Thornton for a design and he obliged with something that he confessed was uncommon. He wanted a circular steeple and colonnade, likely akin to the Roman temple effect he began to crave for the Capitol. Construction began and in an undated letter, he wrote to the board, probably in 1797, he noted that the foundation as laid would not allow his design to be built.(29)

Finally, Thornton rented a solid three story brick house near F and 14th Streets NW from Blodget. It was not far from the Commissioner's office on the other side of 14th Street. F Street was the established route to the Capitol because Pennsylvania Avenue had not been made passable by carriage. On December 26, the president sent a very kind letter in which he congratulated Thornton for the "situation" between the public buildings. "As it is in the midst of your operations,... let me give it strongly as my opinion, that all the Offices, and every matter, & thing, that relates to the City ought to be transacted therein, and the persons to whose care they are committed Residents. Measures of this sort, would form societies in the City—give it eclat...." He urged that all the commissioners make "that part of the city their resident, and compelling all those who are under their control to do the same...." That would be the best way to neutralize the feud between the east and west ends of the city.(30)

That the president would leave office soon made no difference to Thornton. His motive in moving was not to be closer to the Capitol but to gain the president's friendship. Thornton probably was the only commissioner anxious about the change of command, but not so much because of what Adams might think of him. Thornton fancied, as would future historians, that he had a special relationship with Washington and that his success as a commissioner would be measured by what the man who had appointed him after choosing his Capitol design thought of him as a commissioner.

Then Hadfield told Thomas Law that the commissioners wanted to put the Executive Office next to the President’s house. Law and the speculator George Walker who bought most of the lots between Law’s and the Eastern Branch were outraged. They blamed Commissioner Scott. Walker demanded the removal of Commissioner Scott. The president replied that it "certainly is his duty, when charges of malpractice, or improper conduct are exhibited against them, to cause the charges to be fairly examined. This I shall do; in the first instance, by transmitting a copy of your letter, that they may severally know, of what they are accused; that, from the answers I shall receive, ulterior measures may be decided on." The commissioners had to fear that they were being investigated.

Law confronted Scott and on February 4 complained to the president that Scott "amused" him by shewing the President's House on the Map and by pointing out where the [Executive] Offices should be and by anticipating "the future splendor of that part of the City by the residence of Ambassadors and by the Assemblage of Americans who were great Courtiers." Three days later, Law taunted the commissioners with a rumor that "Mr. Cook of Annapolis, Samuel Ringold of Hagerstown and Mr. Tayloe of Virginia resolved last year to build on Square 688." The square was just southeast of the Capitol.

In his February 15 letter to the commissioners, the president almost matched the fury of the protesters: "...the public mind is in a state of doubt, if not in despair of having the principal building in readiness for Congress, by the time contemplated—for these reasons I say, and for others which might be enumerated, I am now decidedly of opinion that the edifices for the Executive Offices ought to be suspended; that the work on the house for the President should advance no faster (at the expence or retardment of the Capitol) than is necessary to keep pace therewith and to preserve it from injury; and that all the means (not essential for other purposes) & all the force, ought to be employed on the Capitol.…"(31)

Then the president realized what he had been doing. He completely backtrack and even forgave Scott for not moving into the city. Then he complimented the board as a whole. "I think the United States are interested in the continuance of you in their service, and therefore I should regret, if either of you by resignation, should deprive them of the assistance which I believe you are able to give in the business committed to your care." For the rest of his life, Thornton paraphrased the letter. As he put it to an October 1797 letter to Dr. Lettsom, the president "wrote a very flattering letter of approbation to the commissioners, testifying his satisfaction and pleasure in their conduct, observing, too, that if any of us retired from office, the country would experience a great loss." Then no longer the president but simply the General, when he passed through the federal city on his way to Mount Vernon, Captain Hoban's artillery militia fired a salute from the Capitol's grounds. The General met with the commissioners long enough to have it pointed out that his signed description of the plan, a prerequisite for the transfer of property from the trustees to the government, did not have the official seal. He sent it back to Philadelphia.(32)

Footnotes to Chapter Eight:

1.Washington Federalist 27 October 1808, The Story of James Hoban on the Irish Emigration Museum website.

2. Hadfield to Commrs, 27 and 28 October 1795, Commrs. records; Hunsberger, p. 46;

3. Scott to GW, 13 November 1795,

4. Commrs to GW 31 October 1795

6. GW to Commrs, 9 November 1795

8. Commrs to GW, 18 November 1795 ; WT to Commrs. 17 November 1795, Harris p. 337, or see footnote to Commrs to GW, 18 November 1795

9. Bryan, History of the National Capital. vol. 1 pp. 315-17.

10. draft letter WT to Pickering, 23-25 June 1798, Harris p. 455;

11. WT and White correspondence, Harris pp. 369-380, 387-392;A biographer of Hadfield thinks Thornton was referring to Gustavus Scott, but Thornton had been Scott's ally in their fight with Greenleaf and Johnson. The latter had ridiculed Thornton's plan. There is no evidence that Scott ever criticized it. King, George Hadfield: Architect of the Federal City; Washington Gazette 6 February 1819.

13. GW to Commrs 22 May 1796 ; Commrs to GW, 31 May 1796;

14. GW to White 5 June 1796; GW to Scott 25 May 1796; Pettigrew 2 pp 544-45, 21 February 1794; WT to Lettsom, 26 November 1795; Pettigrew 2: 549-55; In an April 1794 letter to the commissioners, the president had recounted how he picked the lots he first bought in Square 21: "I am sensible that the No. East quartr of square Number 21. is subject to the disadvantage of a North and East front (not desirable I confess) but these are more than counterpoised in my estimation by the formation of the ground, which, though expensive to improve, on account of a steep declevity on the other two sides, can never (if a quarter of the square is taken, and improved) have the view from it obscured by buildings on the adjoining lots. I was on the ground, and examined it in company with Mr Blodget during the Sale in September last; and after comparing the advantages and disadvantages, resolved to fix on that spot...."; GW to Commrs 11 April 1794

15. GW's diary 13 June 1796;

16. Op. cit,; footnote 4 in Commrs to GW 29 June 1795;

17. GW to Commrs. 26 June 1796; 1 July 1796;

18. Washington Federalist 18 July 1796.

19. Blagden to Commrs, 24, October 1796,

20. GW to Commrs. 29 January 1797; GW to Commrs 20 February 1797 ; Bryan, History of National Capital volume one, pp. 317-8; The Gazette 6 February 1819; Hunsberger, 'The Architecture of George Hadfield;" The president may also have been reacting to what was being called Morris's Folly, the house for Robert Morris designed, built but not finished by L'Enfant. It was not finished because Morris went bankrupt. Most observers blamed L'Enfant's passion for ornaments for delaying completion of the mansion.There were indeed stone carvers in Philadelphia out of work. At least one Italian carver did go down to the federal city. Smith, Morris's Folly, pp. 142-3; footnote 2 in Law to GW circa 10 February 1797

21. Commrs. to GW 31 January 1797.

22. WT to GW, 13 September 1796, Harris pp. 395-7; WT to GW, 1 October 1796 ; Scott to GW, 1 October 1796; GW to Commrs. 21 October 1796; summary of House action 26 December 1796. Harris pp 290. Also see White to Madison, 2 December 1796; GW to Commrs. 21 October 1796; 1796 Division sheet in the Office of the Surveyor Land Management Record System.; Square 170.

23. WT to GW, 14 February 1797;

24. WT to White draft 7 March 1796; for description of Cooke's building, see Smith, Morris's Folly, p. 126.

25. Nicholson to Commrs. 31 August & 24 Sept 1796, 26 October 1796, Commrs. records; Nicholson to Morris, December 9, 1796; For his hopes of good fortune see Scott to Morris, 10 May 1797, Hist. Soc. of Pennsylvania.

26. Clark, Greenleaf and Law in the Federal City, p. 129; Lovering to Nicholson, 12 July 1796, Nicholson Papers Lovering to Nicholson, June 27, 1796; Morris to Cranch April 12 and May 30; Lovering to Nicholson, 7 June 1796, 12 July 1796; Lovering to Morris, 29 April 1796, Morris papers; Langley and Morris contract 26 September 1796, Greenleaf Papers; Scott, Creating Capitol Hill, pp. 82, 79.

27. Prentiss to Nicholson 29 February 1796; Stuart to GW, 25 February 1796; Twining, Travels in America a Hundred Years Ago, p. 102ff ; Law to GW, 11 May 1796. Hallet to Nicholson, 30 July 1795; Hallet to Law, undated, Law Family Papers, Maryland Historical Society. Hallet letter copied with "Observation sur la Valeur des terreins de la Ville Federale soit Washington" Holland Land Company Papers reel 54. In his 1901 book Greenleaf and Law in the Federal City, Allen Clark credited William Lovering for designing The Maples but did not cite any evidence. For Lovering's testimony see "Letter to John Mercer", 7 September 1803 Baltimore Republican; Law to Commrs, recalled but unsourced, alludes to his invention.

28. Lovering to Nicholson, 1 January 1797; Morris to Nicholson 10 January 1797, Haverford College. , 20 January 1797; Dorsey; Prentiss to Nicholson 17 April 1797: Nicholson to Lovering, 17 March 1797, Nicholson Papers; Lovering to Cranch

29. Harris, Papers of William Thornton, p. 582

30. GW to WT, 26 December 1796.

31. Walker to GW, 24 January 1797; Law to GW, 8 February, in footnote find Law to Commissioners, Feb. 6, 1797;

32. WT to Lettsom, 9 Oct 1797, Pettigrew 2: 555-58; GW to Commrs. 27 February 1797.

17. Hadfield to Jefferson, 27 March 1801;Commrs records; 1797;

Comments

Post a Comment