Chapter Seventeen: Patents, Dolley's Snub and John Quincy Adams' Diary

Table of Contents page 274

Chapter Seventeen: Patents, Dolley's Snub and John Quincy Adams' Diary

|

| 189. Col. William Thornton, the Doctor's friend among the enemy |

Thornton's biographers don't dwell on Thornton's relationship with Madison and laud his performance at the Patent Office. As Glenn Brown put it, the nation owes Thornton thanks "for his mechanical knowledge and executive ability. The Patent Office, which has fostered and encouraged the inventive ability of the country began under his management."

In the 21st century, Gordon Brown was a little less thankful. He wrote that Thornton was "so swamped with the growing number of patent applications there was no time for innovation and education." That is, he neglected his own genius and the all-important National University.

Daniel Preston's "The Administration and Reform of the U. S. Patent Office, 1790-1836" gives a glowing account of Thornton's tenure. Preston blames the flawed patent laws, a niggardly page 275 congress, and the cupidity of too many American inventors as the roots of any evils during that 26 year period. To do so, he mutes the conclusions drawn by Thornton's contemporaries. In 1807, Senator Plumer observed of Thornton's messy office "...a little money and labor would remedy the problem." Preston quotes that, but not Plumer's conclusion that Thornton "has too long been guilty of great negligence."(1)

Too many congressmen suspected that Thornton kept a messy office to force congress to raise his $1400 salary and give him helpers. There were also well grounded suspicions that Thornton tried to make money off inventors. For example, in her 1808 notebook for August 6, Mrs. Thornton jotted down: "The Hawkins won't stand to their agreement and are very angry at not getting their patent."(2)

|

| 190. Mrs. Thornton notes disgruntled patent applicants |

At the same time, Thornton had a very low opinion of American inventors. In December 1804, Senator John Quincy Adams

checked on a patent for a constituent. Adams wrote in his diary that Thornton explained that "he

thought it not a new invention— Which indeed he says is the case of

almost all the applications for Patents— And others are for things

impossible." Thornton blamed the patent law since "a Patent cannot be

refused to any person, who takes the Oath, and pays his thirty dollars— " The oath was a simple one: the inventor "hath alleged that he has invented a new and useful

improvement" and swears that his allegation is true.

Thornton gave Adams' an example of a fraudulent invention: "by a Clergyman of Bordentown, New-Jersey,

named Burgess Allison, who has a patent for improving Spirits by

filtration through charcoal, which had been known and practised for many

years—"

Actually, Allison was

not a fraud. He was a rival, and just as Thornton did with Hadfield, his rival at the Capitol, Thornton did his best to ruin Allison's reputation despite his being elected to the American Philosophical

Society in 1789. By the end of 1804, Allison had four patents including two on

improving spirits. Thornton was interested in the same topic. In 1809, he got a patent on "modes of ameliorating spirits and

wine." The master of a boarding

school for boys proved more successful as an inventor than

Thornton. In 1813, Jefferson lauded Allison's loom.(4)

Thornton went out of his way to prove his superior understanding of any invention. In 1809, his old nemesis Stephen Hallet, who had been the first to change Thornton's Capitol design, came to Washington with a water pump he had invented. Hallet later wrote to President Madison that Thornton "examined it Very Carefully, witnessed Some trials and was So kind as to take an active part in the Experiment we have exhibited in the City." Writing from New York City, Hallet offered Madison his water pump, for use at the President's house. He used Thornton as a reference: "As I could not wish to meet with a better Judge of the matter I beg leave to refer your Excelency to that Gentleman’s explanations as to the merits of the machine." Then he put Thornton in his place by suggesting a better reference; "and to Capt Hobben as to the practicability and Utility of its aplication to the President’s House.''(5)

While applicants were the sole judge as to the novelty of their invention, Thornton did more than merely fill in the blanks of the official letter of patent. He

also copied for the files what was called the "schedule" which was a description of

the invention in the words of the inventor. The Patent Office also kept drawings and models of tools and

smaller machines.

Rather than merely copy the inventors' words when he wrote the schedule of their inventions, Thornton might add his own ideas. Inventors did not always appreciate that and accused him of

rewriting their patents in order to gain a share of their profits. In 1808, Thornton bullied Jacob Cist for over a year by changing his patent for making printer's ink from anthracite coal and insisting on becoming his agent.(6)

In May 1808, when Benjamin Latrobe wrote to a friend and characterized Thornton as "a Madman from vanity, incorrect impecuniary conduct, and official intrigue from Poverty," he neatly summarized Thornton's predicament. For all his trying to profit off patents, he was still poor.

However, to be fair to Thornton he was not exactly poor. He sold the house in Lancaster, England, that he had inherited from his Great Uncle Birket, ending his elderly aunt's use of the property. He would claim that he sold it for $20,000. That gave him means to manage his debts which were, as was the case in 1798, "some late heavy losses; not in Speculations, but matters of Confidence...." In this case, he put too much confidence in Samuel Blodget.

In 1802, a court ruled that Blodget owed the winner of the hotel lottery $21,000 in order to finish building the hotel. Blodget decided to raise money by selling his Washington property. In 1803, creditors had him jailed in Washington. Thornton secured a $10,000 bail that gave Blodget bounds in the city so he could work to payoff his debts. The sorry state of Washington real estate made that impossible so in 1808 Blodget broke his bounds leaving Thornton to cover his bail.

Thornton's only substantial statement about his finances was made in a December 17, 1808, letter to his boss Madison. He explained that due to a creditor's unjust demand for payment, he could only escape being held in jail by being out of town until the court met in a week. A few years earlier he had borrowed $150 from Madison, but in this letter he was careful not to ask for a handout even though he had promptly repaid $100 of that loan. Thornton did not divulge the demand to Madison even though it had to do with payments for Gold Company lands in North Carolina, the development of which could well be described as a national boon.

Instead he sketched a balance sheet of large sums and did so in such an abstract way as to suggest not poverty, but that the gods were toying with him:

I have been very unfortunate in the recovery of debts due to me, & have lost many thousand Dollars in the hands of persons whom I trusted. I also became surety for Mr: Blodget’s keeping the Jail Bounds, & in consequence of his breaking them I page 277 remained responsible for more than ten thousand Dollars, he having deceived me in the Amount of his Debts as also in the Security. I have paid above ten thousand Dollars on his Acct. & some hundreds are still due; but knowing the Injuries I suffered his Creditors have favoured me much in point of time. I have many hundred Dollars due to me, but the times being peculiar I cannot in conscience sue for them. I owe some money & lately sold the only house I have in Lancaster (England) to pay it, which discharges a large portion. I offered any of my property here at a valuation, and a mortgage on my Farm as security if any Indulgence would be granted me but this is refused unless I will submit to an unjust demand, and the alternative is a law Suit. Desirous of gaining a little time, for I have received no remittances from the West Indies for two years, I have retired to the Country till the Court meets, which will require me to stay a week longer: but to prevent any loss of time I have brought Patents here to write. The number issued this year will by the end of this month amount to abt. one hundred & sixty, which are four times as many as when I first accepted the Duties.(7)

Obviously one balm Madison could have offered was a raise, but he didn't. Thornton's mother-in-law posted bail which kept him out of jail until his friends on the Supreme Court decided in his favor. Also, in regards to his troubles with Blodget, Thornton wound up owning the house he rented from Blodget and at least one other property once owned by the bankrupt.(8)

But back in December 1808, something more momentous was afoot. In

Thornton's papers there is a draft of a letter to Madison dated

December 9, 1808, just a week before he turned parchment into a crying

towel. The letter began: "that your petitioner has invented certain

Improvements in Steam boats, including modes of propelling the same by

Paddles, or a wheel or wheels at the Stern and improvement in boilers

for Steam Engines for the Same, & for every other purpose where

large & very hot fires are required;..."(9)

Such a petition was the first step in the patent application process, and the next step was to give it to Thornton. The modern editors of Madison's papers include Thornton's letter in Madison's papers. Given that Thornton knew the importance of the date of a patent application, it is likely that Thornton made Madison aware of the petition in 1808. Madison likely knew its implications. While Thornton had no intention of building a steamboat, he wanted royalties from those who did.

|

| 191. Snip of Engraving of Fulton by Benjamin West |

In 1807, Robert Fulton had exploded onto the Washington scene. His primary reason for coming to the city was not to patent his steamboat. He offered something much more exciting. He wanted to demonstrate the effectiveness of his torpedo. He also sent the president a paper he wrote on the development of canals. President Jefferson was very interested in that and in the torpedo. On January 10, 1807, Fulton met with the secretary of the navy. In March, on the president's order, the secretary of war asked Fulton to go to New Orleans and lay out a canal. But he excused himself because he was supervising work on his steamboat. He had the backing of the wealthy Livingston family in New York. He was the first steamboat inventor to have money to burn.(10)

page 278 In New York City, Fulton didn't neglect his torpedo experiments. In July he sent a long report on them to the president along with several drawings. On August 17, his steamboat the Clermont, officially called the North River Steamboat, had its maiden voyage on the Hudson River, also known as the North River, going from Manhattan to Albany at a speed of 5 miles an hour. That cut a four day journey to 32 hours. When he returned to Washington in the fall, he began preparing his patent application for his steamboat. He stayed with Joel Barlow, a wealthy poet and American diplomat who soon bought the late Commissioner Gustavus Scott 's Rock Hill estate for $14,000 and changed its name to Kalorama.(11)

Anticipating Fulton's patent, in January 1809, Thornton did the paper work, and collected the signatures of the president and secretary of state and gave himself a patent for his steamboat and boiler improvements. A fire at the Patent Office in 1836, burned all the patents on file. Thornton's schedule, drawings and descriptions are lost. After working on his drawings for five months, Fulton applied for his patent three days after Thornton got his. On February 11, 1809, Fulton got his patent for steamboat improvements.

Copies of Fulton's patent, schedule, descriptions and drawings are extent, thanks to copies made at the time, preserved, lost and found in 2018. Fulton's patent schedule and accompanying description give the impression that he had been listening to Thornton's critiques of the patent applicants for not showing an understanding of scientific principles. Rather than submit just a nuts and bolts application, Fulton went at lengths to analyze the relationship of water resistance to engine power as affected by paddle design. He noted those relationships at speeds of from 1 to 6 miles an hour. He factored cargo loads as well. Thornton remembered a steamboat that went 8 miles an hour. That made it easy to dismiss Fulton's patent.

Thornton started his campaign to profit off Fulton's steamboat. He assured Fulton that many others, including himself, had done what Fulton claimed to have page 279 invented. Therefore, his patent was useless in that it described nothing new. He offered him the use of his patent that pre-dated his. He also assured him that he would not reveal what no one else knew. A document written almost a hundred years ago described paddle wheels on the side of a boat. Perhaps to lend significance to that, Thornton's patent did not include paddle wheels.(12)

On May 13, Mrs. Thornton noted that when her husband sent his letter to Fulton, he also gave a copy to Barlow. Perhaps, Thornton thought he was making a reasonable, if not friendly offer. For two years, Thornton had socialized with Fulton when he was in town. The Thorntons and Barlows were in the same social circle. However, Fulton did not invite Thornton to Kalorama on February 12, 1809, as he did much of official Washington, "to see the experiment of harpooning, and investigate the principles of Torpedo attack."(13)

Fulton

didn't take Thornton seriously. He deprecated Thornton's "embrio

and useless ideas," and dismissed a succession of his demands over the next five years

from half of all profits to $5000 a year.

Meanwhile, Thornton told other inventors that Fulton's patent described nothing new. He also felt obliged to so inform state legislatures where Fulton asked for monopoly rights. Gaining state monopoly rights was the key to Fulton's business plan. He began to take Thornton more seriously.(14)

|

| 192. Drawings in Fulton's patent application, dated November 20, 1810 |

In January 1811, he challenged Thornton to come up with a better design for a boat that would go 6 miles an hour in still water with a 100 ton load. If Thornton made such a boat that "proved his principles in practice," Fulton promised to assume all its costs and pay Thornton $150,000. Or, if Thornton convinced Fulton "with drawings and demonstration I will join you in the expenses and profit." Thornton later claimed that he agreed at once but Fulton declined to write the terms. There appears be no documentation of that back and forth.(15)

In

February 1811, Fulton padded his patent file by sending more drawings

that clearly showed his unique arrangements of the Bolton-Watt engine,

paddles, and pilot's wheel, plus docking procedures that he trusted were

unique. Then he began a campaign to get Thornton to attest to the

elements in Fulton's design that were unique.

He charged Barlow with the task of page 280 getting Thornton before a judge. In July 1811, Barlow reported that he did but that "the poor fellow can depose nothing now unless it be his bones. He has not recovered from his fever and it is thought by some that he never will." Fulton persisted and told Barlow to warn Thornton that "if pirates can thus copy me he has no chance at any time...."(16) That is, if Fulton's patent was useless so was Thornton's.

Thornton was incapacitated for a month and a half with what his doctors called rheumatic fever. He submitted to Benjamin Rush's

stentorian remedies, calomel and bleeding, as well as fizzy waters

bought to him by Tayloe. He dictated at least one letter during his

ordeal, to President Madison about horses. When

Thornton recovered, he refused to sign off on Fulton's claims.(17)

In

1812, Fulton and his backer Robert Livingston published a notice

nationwide that outlined the only prudent way for anyone interested

in building steamboats to proceed. Their company would license

steamboats on any river but the Mississippi and in New York, where

they had monopoly rights. They would only take half the profits after 10% was

deducted for capital expenses.(18)

According to his wife's notebook, on the evening of April 11, 1812, Thornton "had a long talk" with the president "respecting Fulton & c." Thornton likely pressed the importance of rewarding his own steamboat claims. It did not go well. He wrote to a friend: "If I had never accepted any Employment under the last & present administration I should I really believe have been many thousand Dollars better in Situation than at present. Man is a very selfish Animal." He added a couplet: "I really think a Friend at Court/Is but a kind of Friend in sport."(19)

Meanwhile, Fulton complained to the powers that be in Washington that it was unfair for the government's officer in charge

of patents to attack his patents. Secretary of State James Monroe

told Thornton to stop giving himself patents. Thornton insisted

that being the head the Patent Office should not preclude him from

expressing his opinions and his low salary justified his trying to

make money off his own patents. He won the argument and in 1814 got a patent for

steamboat paddles.(20)

In that same year, Thornton also published a pamphlet curiously titled "Short

Account of the Origin of Steamboats Written in 1810 and Now

Committed to the Press." The stated purpose of the essay was to prove

that John Fitch invented the steamboat. Thornton recalled that the first boat

only reached three miles an hours. Then he, that is Thornton, rallied the company's board

to make a second boat that would go eight miles an hour. Without

engineers or previous knowledge of steam engines, they did just that at a

public demonstration in still water off Philadelphia. No one else quite remembered it that way.

Their second boat did well and carried passengers, advertising service on the Delaware River until the boat broke down.

Thornton didn't explain why he waited until 1814 to publish what he claimed he wrote in 1810. Of course, he had hoped to make a financial arrangement with Fulton. Thornton also knew that dating documentation as early as possible was crucial when courts decided patent disputes. However, by delaying publication he also prevented two crucial witnesses from challenging his claims.

page 281 While Fitch's boat made waves in the Delaware, Fulton was in Europe. Thornton shared evidence that Aaron Vail, an American consul in France who had contracted to be Fitch's agent, gave the specifications of the boat to Fulton. He also appended an affidavit from the respected

inventor Oliver Evans that Henry Voight, who had assisted Fitch, credited Thornton with the idea to

put paddle wheels on the side of the boat.(21)

Vail died in 1813 and Voight died in February 1814. Then Thornton published his history. Fitch had doted on Thornton's enthusiasm. But when the "geniuses" of the company were stumped, Fitch recalled that Henry Voight "pointed out ways to remedy those defects, when consternation sat silent in every brest...." Thornton assumed that his ideas based on the scientific principles involved made him the inventor despite his doing nothing to assure the practicality and utility of his ideas.(22)

Fulton died of over exposure to the cold in February 1815. Thornton took credit for his death. In his memoir, written during the Civil War, Benjamin Ogle Tayloe remembered that: "Dr. Thornton told me he killed Fulton with his last pamphlet." Fulton had long had issues with his lungs.(23)

Their dispute continued. To inventors and entrepreneurs, Thornton presented the demoralizing spectacle of the officer in the government in charge of patents going out of his way to attack Fulton's patent and promote his own. However, Thornton's biographers quote Benjamin Latrobe's reply to a letter Thornton sent attacking Fulton as proof of Thornton's moral victory in the dispute.

Latrobe tried to build a Fulton steamboat in Pittsburgh, lost money and pressed Fulton to raise money by suing other steamboat builders. He wrote to Thornton that Fulton "always contrived to put me off," and added "this portrays a bad conscience." Latrobe rued not seeing "the selfishness and low cunning of his character. I have been his dupe and am now suffering the punishment for my credulity."(24)

That said, Latrobe wished that Thornton had not printed his pamphlet because it would only complicate matters for people building steamboats. Thornton's own patent and boast that Fitch's boat was actually his invention had to be viewed as a threat. That may explain why Latrobe flattered Thornton.

Ironically, at the climax of his battle with Fulton, Thornton decided to have a craftsman actually build one of his ideas. That in turn led to Thornton's shining moment in August 1814 that assured that Thornton will forever be remembered as the savior of the Patent Office. The somewhat convoluted story has to be told because Thornton's boasting contributed to his losing the friendship of the Madisons, and that in turn offers more evidence that he didn't design the Octagon.

That friendship was already in jeopardy. In 1811, Thornton was elected a captain in the Columbia Dragoons, a horse militia. Then in 1813, to his shock, the selection of a major was made by having two longer serving captains draw lots. In response, Thornton came up with a plan to improve his position in the militia and with the president. He wrote to Tayloe, who after spending more time in the city became the colonel of the horse militia. Thornton asked him to persuade the president to become the "Commander in Chief of this District, in the same manner as the Governors of States." If he did, he would have to appoint aides to carry out his orders. In states, two aides came from the militia. It was not unknown for such aides to be given the rank of page 282 colonel.

Evidently Thornton had already broached the subject with the president because in his June 8, 1813, letter to Tayloe, he explained that "The President … is actuated by extreme modesty & unobtrusive Delicacy in declining to make, hitherto, such appointments, because his Predecessors have not furnished an Example: but his Predecessors have never been engaged in actual war, since the Assumption of the District of Columa: & consequently were never in the same predicament.”

Thornton belittled the president's reasoning: "....Reason may require her votaries to walk in a line untrodden." Then he pleaded his case: "...if the president should consider the manner in which I have been treated, from a gentleman of his feeling, my case would claim from him some attention, and I know not of any way now to repair that breach of correct military conduct toward me except by such an appointment...."

What Tayloe or the president thought of Thornton's letter is not known. It wound up in Madison's papers so evidently Tayloe gave it to him. If she saw it, Mrs. Madison might not have been been pleased. As a last thought on the matter. Thornton opined that “Mrs. Madison would perhaps wish her Son to be the other [aide]; which would not only give him rank, but exempt him from common militia duty.”(25)

Her 23 year old son went to Europe with peace negotiators. Thornton stayed with the militia, but while the British refrained from menacing the capital, the militia remained inactive. Thornton had time to build a musical instrument. In a June 27, 1814, letter to Jefferson about looms, Thornton revealed that for the last several months, he had a man building it. He described it as having "68 Strings which by Keys in the manner of the piano Forte, will give all the tones of the violin—violincello—bass—double bass &c—...."(26)

When the British army came close to the capital, Thornton was briefly called to active service. His troop reconnoitered British movements at the mouth of the Potomac. He was not at the Battle of Bladensburg.(27) He fled to Georgetown as the British invaded and burned government property.

Then at breakfast the next day, he heard that the British were still burning government buildings. He was especially concerned about his musical instrument. As he put it in a letter to the National Intelligencer that he wrote a few days later: "I was desirous not only of saving an instrument that had cost me great labor, but of preserving if possible the building and all the models."

On the 25th, Thornton returned to the city alone, found the British army burning the War office next to the President's house and persuaded them not to burn the Patent Office which was then in a corner of the building once destined to be Blodget's grand hotel. The government had bought the building and Latrobe refurbished it in 1810 to accommodate the Post Office as well.

British officers gave Thornton permission to get his instrument, and then he persuaded the officers to spare the building and all the models of inventions. Thornton left the instrument in the building and returned to Georgetown.

When Thornton returned to the city on August 26, he found that, save for some of their wounded, the British army had gone. He called on the mayor and found that he had gone. He realized that he was the only justice of the peace in the city.

Acting in that capacity, he claimed that he organized a guard for the President's house, Capitol and Navy Yard. He later wrote that at the Navy Yard, "I went and ordered the gates to be shut, and stopped every plunderer." He ordered provisions for the wounded: "I appointed a Commissary, and ordered every thing that page 283 the Doctor thought requisite, for which I would be responsible. The [British] Sergeant requested my protection for all his men. I told him they would be protected;... He promised to obey every order. I gave orders and he fulfilled them. Some stragglers, I understand, were taken up, and perfect order kept throughout the city."(28)

|

| 193. Capitol after the British burned it |

The president, secretary of state and attorney general returned to the city on the 27th. On the 28th they rode to the Navy Yard. Thornton followed them. Secretary of State Monroe had seen service as an officer during the Revolutionary War and the president intended to make him secretary of war. In the meantime, he placed him in command of military operations. In a letter he wrote to his son-in-law on September 7, Monroe recalled: "...we were followed by Dr. Thornton who stated to the president that the people of the city were disposed to capitulate. The President forbade it. He pressed the idea as a right in the people, notwithstanding the presence of the govt. I turnd to him, and declard, that, having the military command, if I saw any of them, proceeding to the enemy, I would bayonet them. This put an end to the project. The doctor retird, and afterwards changd his tone."

Thornton took Monroe's threat very seriously. In her diary, Mrs. Thornton wrote that to defend the city, her husband "distressed us more than ever by taking his sword and going out to call the people...." Alexandria capitulated, the British ships resupplied and then sailed back down the Potomac. Thornton sheathed his sword, and obeyed orders to remove models from the page 284 Patent Office so congress could assemble there.

Dolley Madison's sister and her husband Richard Cutts lived next door to the Thorntons. On September 8, Mrs. Thornton visited the ladies: "I had long conversation with Mrs. Cutts and Madison today. They have listened to many misrepresentations and falsehoods concerning Dr. T_ and of course are not pleased with him."(29)

Thornton learned that he had a problem before his wife did. On August 30, he wrote a letter to the editor of the National Intelligencer: "Hearing of several misrepresentations, I think it my duty to state to you in as concise a manner as the various circumstances will permit, my conduct in the late transactions in this City." The letter was published on September 7th,

Thornton's story of how he saved the Patent Offices still resonates with historians. His plea to British officers is often quoted: the building "contained hundreds of models of the arts, and that it would be impossible to remove them, and to burn what would be useful to all mankind, would be as barbarous as formerly to burn the Alexandrian Library, for which the Turks have been ever since condemned by all enlightened nations."

Then

he explained that he never urged capitulation. He had wanted to remind

the British "that it was understood when their army destroyed the

public buildings and property no other would be molested, and to request

therefore they would not permit their sailors to land." When he learned

"that the President had refused to hear of a deputation," he rode to

him and explained "that the people on all sides deprecated a mere shew

of

resistance." When he learned that troops had rallied and "would defend

the city to the very

last," he "rode in all directions, and called to arms...."(30)

He made no mention of the threat of a bayonet in the back, nor his novel theory that the "the people" had a right to surrender the city even if the government had returned to the city.

|

| 194. James Monroe |

Blake recalled that Thornton "urged me to send a deputation

to the British fleet then ascending the Potomac and reprobated the idea

of resistance." He mocked Thornton's other

claims, suggesting that a violent storm was the reason the British didn't burn

more government property. He also congratulated him for saving his musical instrument. (After Thornton died, his wife asked an instrument maker to examine Thornton's invention and he "could not do any thing with it....")

Finally, Blake reminded Thornton that before the invasion he had refused "furnishing our Citizen Soldiers... with such refreshments as they had been in the habit of getting when at home, assigning as a reason, that he was opposed to the war, and would not give a cent toward carrying it on."(31)

In his reply, Thornton mocked Blake as a mere tax collector and made a stanza of doggerel in which "Blake" rhymed with "snake." The editor wrote at the bottom of the letter "The Public and the editor conceive that this sort of BADINAGE to be unsuited to the times and expect it to cease." Along with his badinage, Thornton didn't deny that he was against the war. page 286 He was "a man of peace," and his "situation has nothing to do with politics or war, being a member of the great Republic of Letters, and considering it a duty to labor for the happiness of all mankind."

Blake replied to Thornton's second letter and delved deeper into his fraternizing with the enemy. He claimed that Thornton gave "the key to his office to a British officer..." He also was seen "privately communicating with a British officer of distinction." That all added up to "base humiliating and servile ('not spirited') conduct to the British when here." Blake concluded "Doctor T has been living upon the Public Treasury for near twenty years, and I dare say he cannot point to a single service that entitles him to the patronage of the government."(32) The Madisons moved into the Octagon house on September 8, a week before Blake castigated Thornton for doing nothing.

In some versions of the burning of the capital, Thornton not only gets credit for his noble defense of the Patent Office but also for designing the house into which President Madison moved when he returned to the city.(33) Those versions leave one with a warm feeling for the gratitude the Madisons must have felt for Thornton for his designing the house where they lived for six months in such special circumstances. However, Thornton had had nothing to do with the Octagon. Mrs. Thornton's never alluded to it in the detailed diary which she kept during the crisis. Later, in her notebook, she mentioned going to Mrs. Madison's "drawing room," but didn't note where it was.

Thornton seemed to have enjoyed the remainder of the war vicariously, but not with an intrepid American dragoon in mind. The high British officer that Thornton had visited after the burning of Washington was Col. William Thornton. In June 1815, Thornton wrote to Col. Thornton who had recovered in time to fight in the Battle of New Orleans.

Thornton gushed over the colonel's gallantry and discussed European politics. He closed with the happy report that the buildings the British burned would be rebuilt, and that efforts to move the nation's capital elsewhere failed. He took credit for that: "they now would have succeeded if I had not prevailed on Major Waters and Col. Jones to spare the Patent Office containing the Museum of the Arts, which temporarily accommodates the Congress. Thus it was observed one William Thornton took the city, and another preserved it by that single act."(34)

When her husband's second term ended in March 1817, Dolley Madison made farewell visits to all her friends in the city, but not to Mrs. Thornton. She was devastated. Thornton noted the slight in a letter to Madison and added, " I have long had to lament a marked distance and coldness towards me, for which I cannot account." Thornton's war story which he delighted in retelling probably didn't help.(35)

Given his posthumous reputation, it would seem that Thornton should have taken a leading role as the nation rebuilt and better fashioned its identity after General Jackson’s army won the Battle of New Orleans. Even if Madison didn’t use Thornton to restore the Capitol, with the death of Fulton, Thornton could have played a major role in developing the steamboat as it became the avatar of national progress. However, Thornton did not replace Fulton. An inventor who doesn't make what he invented never captures the public's imagination. Worse still, Thornton took pride in not building what he claimed were his inventions.

In 1811, when John H. Hall applied for a patent for a breech loading rifle, Thornton page 287 claimed he had already invented it. Hall relented to Thornton's pressure and agreed to a joint patent. After the war, when Hall proposed to manufacture the rifle, Thornton objected and only wanted to license the patent.(36)

At the same time, Thornton simplified his story about his steamboat. By 1819, he relegated Fitch to "a poor ignorant and illiterate man" with whom he worked for "about a year and a half." His boat "did not exceed two or three miles an hour." Then Thornton "engaged" to make the boat go "eight miles an hour within 18 months." In one year he succeeded. Then a boat also rigged with sails was designed to go ten miles an hour in dead water and to be sent to the Mississippi. When he visited his mother in Tortola, his partners failed and sold the boats "and the whole apparatus." Fulton learned all about the invention because in Paris he "had seen my papers describing the steam boat."(37)

|

| 196. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams |

His story was neither accurate nor impressive. On April 26, 1819, John Quincy Adams, Secretary of State and thus Thornton's new boss, went to the Patent Office to do a favor for an American correspondent in Europe who wanted to patent "a simplification of Fulton’s Machinery." Adams wrote in his diary that Thornton showed him that his friend's patent differed "nothing in principle, and very little in mode from several other models of Patents to produce the same effect."

Then Thornton told him "the whole Story of his own Steam-boat, which actually ran upon the Schuylkill several years before Fulton’s, but which failed of ultimate success, merely by his want of Perseverance and pecuniary means..."(38)

In 1820, Adams bought the house next door to Thornton. They were next door neighbors until Adams moved in the President’s house in 1825. Thanks to Adams’ diary, principally about page 288 official business and the ambitions of others, a measure can be made of Thornton’s importance.It would seem that just as he told Adams about his steamboat that Thornton would tell his version of the design of Capitol. Evidently, he didn't. Thornton did not come across to Adams as an architect. When Adams needed a plan for a stable and carriage house to better accommodate his family on F Street, he hired a Mr. Sim, and did not consult with Thornton.(39)

Only once did Adams allude to any discussion of the Capitol with Thornton. When none of the entries in a design contest for the tympanum above the east portico entrance to the Capitol would do, President Adams mentioned three men including Thornton who might come up with a winner. On July 17, 1825, at a time when Adams could not devote much time to his diary, he noted: "Visit from Dr. Thornton - Design for the Tympanum" and below that "Portrait of Bolivar." Whatever Thornton might have said about the design, Adams came up with an arrangement that he called his own. Likely most of the conversation with Thornton was about the Liberator of South America.(40)

|

| 197. Adams's Tympanum: the sculptor Persico wanted Hercules; Adams decided on Hope instead. |

By that time Simon Bolivar had

liberated South America as far south as Peru and Bolivia. Thornton had

vicariously fought in every battle against the Spanish. He had even fancied himself a secret agent for the revolutionary who preceded Bolivar.

In 1808, during the treason trial of Aaron Burr in Richmond, General Eaton, US Army, testified that he was asked by "a gentleman near the government... if I would take a command under the celebrated General Miranda." Just as he rejected Aaron Burr's plan to overthrow the American government, Eaton was not attracted to "the project of darkness" aimed at liberating Venezuela from the Spanish crown. He got the conspirator to admit that he wasn't authorized by the US government. A defense attorney asked: "Who was that man? Answer: Dr. William Thornton."(41)

Thornton's possible violation of the Neutrality laws did not lead to an investigation. Politically, the revelation made little difference. During the 1806 trial of Americans who helped arm or fight with Miranda, including John Quincy Adams' brother-in-law William Smith, the page 289 defense tried in vain to link Jefferson and Madison to Miranda. Thornton was decidedly small fry in that regard.(42)

But Thornton's association with Miranda was not forgotten. In a February 18, 1818, letter to Madison, President Monroe raged that Thornton's Miranda episode had been eclipsed by a dumbfounding report that former Attorney General Rush had supported a plan hatched by Thornton for the government to buy East Florida for $1.5 million from an adventurer named McGregor.

Monroe fumed: "Of the absurdity of such a statement, and the impossibility, that Mr Rush, should have warranted it, by any thing on his part, both his character & that of Dr Thornton seem to afford full proof." In his reply, Madison did not impugn Thornton's character, but marveled that anyone could come up with such a stupid idea. (43)

In 1815, Thornton published his constitution for the union of North and South American republics. By then, no one had to hide their sympathies for South American revolutions. In that regard, he projected another monumental building of which John Quincy Adams must have heard. Up in Quincy, it gave his father a good laugh.

A friend wrote to the former president about Thornton's "....One Grand Republican Government, to be placed under the surveillance, and legislation, of a Congress of Deputies from all the Cities, and all the States, not only of South, but also of North America, who should hold a permanent sitting on the top of Mount Chimborazo, twenty thousand feet above the level of the Sea;..."(44)

Thornton knew the mountain well because in 1804 after Baron von Humboldt climbed it doing scientific research, he had dinner with the Thorntons when he spent a week in the federal city.

The younger Adams wasn't amused by Thornton's South American plans. He had set out to effect the peaceful acquisition of Florida. Meanwhile, Thornton was conducting diplomacy on his own. He wrote about his activities in an article signed "Columbia." The British minister in Washington told President Monroe that he was solicited by an agent for the revolution in New Grenada sent to him by Thornton. The president was not amused. When Thornton demanded a conference with Monroe to explain his association with "South American Patriots," Adams told Thornton that "the President said he would not see him, nor have any conversation with him upon any thing, unless it were Patents, and very little upon them."(45)

Thornton persisted; two years later when Thornton demanded a diplomatic post in Latin America, Adams explained to him "that as he had always been a very ardent South-American Patriot, perhaps the President might think a person more cool, would suit better for the impartial observation necessary to such an agency— [Thornton] thought that very strange; for in his opinion, it was precisely that which made him peculiarly fit for the Agency."(46)

A few months earlier, Adams had already concluded "The Doctor is the most indefatigable, and irrepulsable candidate that I ever knew."(47) He could also be repulsive.

He showed Adams a letter offering a deal by the House Chaplain, Burgess Allison, to travel about the Country as Vice-President of the general Baptist associations of Ministers, and support Adams for president in return for his being appointed Superintendent of the Patent Office after Thornton was sent as "Agent to South-America." Adams wrote in his diary that "Neither Allison himself, nor Dr Thornton, appears to have a misgiving of Conscience as to the political purity or moral delicacy of this broad hint. To me it is page 290 very disgusting—"(48) In 1804 in a conversation with Adams, Thornton had singled out Allison as a fraudulent inventor.

Adams

forgave Thornton. In an 1822 diary entry, he

put it this way: "The Doctor is a native of the Island of Tortola; a Man

of learning, ingenuity, wit and humour; well meaning, good-natured, and

mainly honest, but without judgment or discretion. I told him there

would probably not be an early appointment of a Minister at Rio

Janeiro."(49)

Adams also knew that Thornton was underpaid. Congress refused to raise his $1400 salary. Adams warned him to stop ridiculing congressmen. "The good-will of every member is important to him; but he cannot resist the temptation, of passing a joke upon them;"(50)

Because he was underpaid, Thornton applied for any appointment that would raise his salary. In 1822, he

chaffed at his not being appointed Commissioner of the Land-Office. A

politician from Ohio got the job. Adams wrote in his diary: "The Dr

thinks it very absurd to go several hundred Miles into the States, to

seek public Officers which might be as well filled, by inhabitants of

the district of Columbia— He thinks they have an equitable right to be

preferred to all others."(51)

Despite all his eccentricities and his over reaching vanity, Thornton would redeem himself. One day Thornton came to apply for a well paying auditor's job left vacant by a death the previous night but he also brought Adams "a dissertation upon Comets."(52)

Sometimes Thornton gave Adams unalloyed pleasure. One spring evening in 1821, "we spent the Evening at Dr Thornton’s where we were entertained with Music— Mrs Thornton performed on the Piano, and sung Handels’ Anthem of 'Comfort ye my People'—much to my satisfaction."(53) Adams played chess with Thornton, once Adams went to the Quaker meeting with Thornton,(54) and Thornton frequently joined Adams at his usual Sunday services. Adams admired Thornton's drawings and objets d'art and laughed at his jokes, although one evening he dismissed the latter as "buffoonery."(55) Sometimes it went down better and Adams jotted: "Thornton gave us after dinner a perfect surfeit of buffoonery."(56)

As for Thornton's borrowing money, Adams seemed to manage that. When Thornton asked for a loan, Adams simply said no. In the spring of 1822, Thornton asked Adams for an advance on his pay. He told Adams that the tax-collector had just "seized all his furniture, for the payment of 220. dollars of taxes for the last three years..."(57)

It was likely difficult for Adams to fathom Thornton's poverty as he continued racing his horses. But he rooted for his neighbor. In the fall of 1821, Adams wrote in his diary that he detected Thornton's "great disappointment" when Rattler lost.(58)

In

1823, Thornton discussed his ideas about the after life with Adams:

"Dr Thornton called this morning, and gave me some of his ideas about

body and soul. He is writing a pamphlet or dissertation in which he will

broach some of his own strange ideas. He denies the existence of the

Soul, but believes in the immortality of the body— And he has a theory

of suspended animation in which he vouches certain wonderful phenomena,

to support the wildest absurdities—" One

of those wild absurdities may have been his claim that he offered to

bring General Washington back to life.(59) page 291

After he moved into the White House, Adams kept track of his old neighbor whose health was poor during the last three years of his life:

...I

called to see Dr Thornton who is ill in bed. He has been for some

months much out of health, but had apparently recovered, and was last

Sunday Evening with Mrs Thornton at my house— He was very suddenly

seized that same Night, and has not since left his bed— He is

exceedingly reduced both by his disease and his remedies— He can

scarcely speak, but retains his facetious humour, and his South-American

ardour— He was very fearful that the British would cut a canal for Line

of Battle and India Ships, and obtain an exclusive right of navigating

for forty years.(60)

In

those days government officials were not replaced or expected to resign

because of bad health. Adams wasn't checking on Thornton for that

reason. He knew that Thornton's clerk, William Elliot "has done most of

the business for some years and was eminently qualified, by his

knowledge of mechanics and of all the mathematical Sciences."(61)

After Thornton's funeral on March 30, 1828, Adams quenched any dregs of pity by penning a flowing eulogy:

People seemed to scatter petals on Thornton's grave without ever awarding him a laurel. In a brief biography of her husband, Mrs. Thornton regretted that he failed to gain the unassailable fame he craved. She credited him for genius in many fields - "philosophy, politics, Finance, astronomy, medicine, Botany, Poetry, painting, religion, agriculture, in short all subjects by turns occupied his active and indefatigable mind." She concluded that "had his genius been confined to fewer subjects, had he concentrated his study in some particular science, he would have attained Celebrity."(63)

She didn't mention architecture. As the finishing touches were put on the Old Capitol in 1828, it appears that no one, including Thornton, reflected on Thornton's contribution to the building.

|

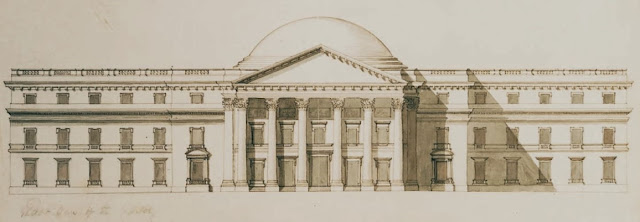

| 198. Capitol 1832 |

page 292 A grand staircase below the dome ended the argument between Hallet and Thornton over the entrance of the East front of building. The portico grinned below the dome with 17 columns. Thornton's design only had eight. The dome seemed equally excessive and bullied the wings of the building. Trumbull's paintings in the Rotunda seemed to get more consideration than either the House or Senate. The roofs of each wing peaked high above the balustrades. For naught had Hadfield been banished.

As it turned out, only two things were of immediate value in Thornton's estate: slaves and horses. The Quaker lad raised in Lancashire very much became a Virginia gentleman.(64)

Thornton valued his estate at $69,330.(65) But he left debts. His widow's horse

and carriage were taken away by creditors a few weeks after the doctor

died. There were eleven

slaves to sell valued at $2,665. He did provide for their eventual

freedom after the death of his wife and her mother, provided that the

slaves were educated. He wanted them to have a plot of land or a ticket

to Liberia.(66)

In

1816, southern politicians and northern preachers had founded the

American Colonization Society, which, acting almost as an arm of the

government, tried to send freed slaves to Africa in hopes that would

prompt more to be freed in the United States. Thornton was one of many

who signed the founding document, and one of its 13 vice presidents. There

is a draft of a letter in Thornton's papers welcoming the society. He

provided ammunition to use against any who doubted that blacks would

want to go back to Africa. In 1787, blacks in Rhode Island page 293 responded to

his call: "They were delighted with the prospect, and in a few weeks

informed me that two thousand were ready to accompany me."(67) Estimates of American blacks who moved to Liberia before the Civil War range from 11,000 to 16,000.

None of his slaves got freedom or a ticket to Liberia. His will cautioned that they could be sold if they "behaved so improperly as to require it." There is no evidence that he ever freed a slave. In 1808, he sold Joe Key to a North Carolina congressman. He was the slave Thornton entrusted to take Driver to Mount Airy. Key escaped in Alexandria and in 1812, when he was found on the farm next to Thorntons' farm, Thornton sold him again.(68)

The executors of his estate principally looked to his stable to save his wife from debt. The advertisement for the sale ran nationwide. The horses did raise money. Rattler wound up in Kentucky. Henry Clay almost bought him and did buy the Dutchess of Marlborough for $500. Mrs. Thornton wrote out the pedigree and Thomas Peter assured Clay that she "was a mare of fine bottom and great speed & if she had an experienced trainer she certainly would have ranked as a 2nd if not a first rate nag."(69) Thornton would have bristled at his old friend calling the Duchess of Marlborough a second rate nag.

If in his own mind, Thornton ever entertained the thought that he was second rate, he likely raised his self-esteem, as we all do, with warm appreciation of his own goodness. His wife of 38 years exalted: "his philanthropy led him to try to enlighten mankind, and benefit them by his study and observation, and if could not accomplish all his ardent and benevolent mind sought to attain, he will have credit with mankind for his zeal in the Cause of learning and Science and Virtue."(70)

Ironically, his fame rests almost entirely on his purported genius as an architect. Yet, if an architect is one who facilitates building, then Thornton was not the First Architect of the Capitol. He did not design the Octagon. With contemporaries he gained far more fame and infamy than his talents either as a bureaucrat or collaborator/revolutionary warranted. He was sociable, a generous host, and his eccentricity and buffoonery leavened the the more tedious traits of a know-it-all. Like many in any nation's capital, he could be devious and hypocritical. But he had no sense of proportion, was never politic, and thus usually harmless.

As much he begged for it, he was never sent away to South America or anywhere else. In a perverse way, the city needed to keep him. For presidents, his "ideas" about the Capitol shielded them from congressional interference. For congressmen, his envy and anger at architects enabled their unceasing complaints about and interference with whoever tried to get the Capitol built. Thornton's ego otherwise proved a valuable check on bothersome outsiders. Once sent to the Patent Office, not a few inventors learned from Thornton that there was nothing new under the sun.

1. Brown, Glenn, Architecture Record, 1896; Brown, Gordon, Incidental Architect, p 76; Preston, Journal of the Early Republic, "Administration of Patent Office...." Vol. 5, No. 3 (Autumn, 1985), pp. 331-353; Dobyn p. 45.

2. AMT notebook, volume 3, image 47

3. American State Papers Misc. vol 2

p. 193

4. JQA diary, 27 December 1804 ; Preston, p. 344; Jefferson to Allison, 20 October 1813

5. Hallet to Madison, 9 September 1809

6. for on-line copy of a patent from that period see: "James madison signed patent to pendulum pumps" university archives auctions; Dobyn pp. 47-8

7. Blodget's financial problems are a described in a monograph on his Philadelphia mansion, and a court case, Bickley v. Blodget; WT to Madison, 17 December 1808 ; on sale of Thornton's Lancaster house see and his other financial problems, WT to Madison, 2 September 1823

8. Thornton v. Carson's Executor, Google Books ; National Intelligencer ad 14 May 1813 (pdf)

9. WT to Madison, 9 December 1808

10. Jefferson to Fulton, 16 August 1807, ; Century Magazine, vol. 78, 1909 p. 834

11. Fulton to Jefferson 9 January and 28 July 1807 ; AMT notebook, image 24 - Some source suggest that Scott had changed the name to Belair, but in her notebook Mrs. Thornton referred to it as Rock Hill.

12. American State Paper, Misc vol one p429; vol. 2, pp 133, 136; see at photostat of Fulton's patent specifications at (Mostly) IP History blog; Dobyns, "Dr. Thornton Takes Charge."

13. Fulton to Jefferson, 9 February 1809; AMT notenbook vol. 3, Image 66, February 12; May 13; AMT vol 3 image 6,7

14. Dobyns, pp. 52-53,; Sutcliffe, Robert Fulton, p. 351; for WT letter to Virginia legislature see appendix #2 Thornton, Short Account of the Origin of Steamboats Written in 1810 and Now Committee to the Press, 1814

15. Clark pp. 186-7

16. (Mostly) IP History blog; Century Magazine vol. 70, 1909 pp. 832-3

17. AMT papers, vol box 3, 10 July 1811 image 125ff ; WT to Madison, 3 August 1811

18. Published newspaper notice dated New York May 21, 1812

19. AMT vol. 3 image 181; Thornton to Steele, 18 April 1812, Papers of John Steele NC Digital Collection page 219

20. Dobyns, Kenneth, History of the Patent Office, chapter 9,

22. Westcott, Life of John Fitch (google books), p.157

23. Dobyns; Tayloe, B.O., In Memoriam

24. quoted in Graye, Michelle, Thomas Jefferson's Washington Architect: William Thornton

25.. Clark, Dr. and Mrs. Thornton, p. 182; Tayloe to Madison, 25 July 1807 ; Thornton to Tayloe, 8 June 1813

26. WT to Jefferson, 27 June 1814

27. Monroe to Madison, 21August 1814

28. National Intelligencer 7 September 1814; on-line copy of Thornton's letter to the newspaper at http://www.myoutbox.net/poni1814.htm ,

29. Journal of Columbia Historical Society, 1916, "Mrs. Thorntos Diary Capture of Washington" pp. 177, 181; Monroe to Hay, 7 September 1814

30. National Intelligencer, September 8, 1814, on-line copy at Dobyns http://www.myoutbox.net/poni1814.htm

31. Op. cit. September 10, 1814 on-line copy at Dobyns http://www.myoutbox.net/poblake.htm ; AMT papers, Box 4 reel 1 Image 7

32. Natl. Intelligencer, 13 & 15 September on-line at U. of Texas

33. Howard, Mr. and Mrs. Madison's War, p. 253

34. WT to Col. WT, 24 June 1815, Gilder Lehrman Institute, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/collection/glc07367 (no longer available without registered log-in)

35. WT to Madison 3 March 1817

36. Preston pp 345-6.

37. WT to Henry Hill 20 April 1818, in Clark, "Dr. and Mrs. Thornton" pp. 187-8; See Thornton's 1790 letter to Vining, footnote #3 Chapter Four for his celebration of Fitch's genius.

39. several diary entries describe Adams' house hunting

40. JQA diary, July 17, 1825

41. American State Papers Misc. vol. 1, p 539

42, Adams, Henry, History of the United States During Second Administration of Thomas Jefferson, pp. 195ff

43. Monroe to Madison, 13 February 1818; reply 18 February 1818

44. James Lloyd to John Adams, 7 April 1815; reply 22 April april 22, 1815

45. JQA diary February 14, 1818 ; see also the diary entry for February 13

46. JQA diary Feb 17 1820; 47. Ibid. Feb 2, 1821

48. Ibid. June 8, 1820 ; 49. Ibid. September 22, 1820

50. Ibid. May 18, 1822; 51. Ibid. Sept 20 1822

52. Ibid. Feb 28, 1824; 53. Ibid. April 8, 1821

54. Ibid. March 25, 1821 ; 55. Ibid. January 10, 1820

56. Ibid. November 30, 1819; 57. Ibid. October 3, 1822 Dr Thornton called at the Office, with a proposal to borrow money, which I declined—; Ibid. April 30, 1822

58.October 16, 1821, In his next day's entry, Adams wrote "Dr Thornton won this day’s race" which evidently gave little joy to Thornton;

59. JQA diary, June 25, 1823 ; Harris, p. 528.

60. Ibid. May 22, 1825; 61. March 29, 1828

62. March 30, 1828

63. Clark, Dr. and Mrs. Thornton, p. 199

64. John Tayloe who died in Virginia on March 23, a few days before Thornton, left sizable sums to his children and others. He freed and endowed his manservant Archy Nash with $100 a year. https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Tayloe-16

65. Jenkins, Tortola, p. 61.

66. Berlin, Jean V. "A Mistress and a Slave: Anna Maria Thornton and John Arthur Bowen" Proceeding South Carolina Historical Associationy, 1990 (pdf) p. 70

67. Sherrwood, "Formation of Amer. Col. Soc." Journal of Negro History 1917; Hunt, Galliard, "William Thornton and Negro Colonization," Amer. Antiquarian Soc. 1921, pp. 57ff.

68. AMT notebooks vol 3 Image 38, 75, 141 (for sale of another slave; National Intelligencer. ad dated 16 May 1808)

69. Henry Clay Papers, Clay to Mrs. Thornton, 2 November 1828; American Farmer no. 6 vol. 10 p. 28

70 Clark, "Doctor and Mrs. Thornton" p. 199.

Comments

Post a Comment