Chapter 13: Mrs. Thornton's Diary

Chapter 13:

Mrs. Thornton's Diary and All of the Doctor's Horses

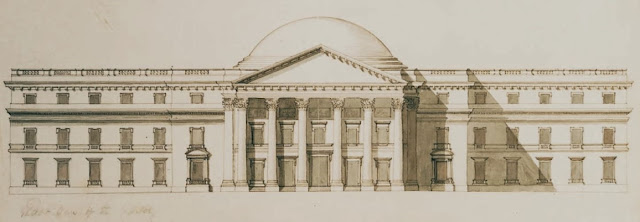

Orientation of Thornton design if in lot 17 Square 171

In 1800, Mrs. Thornton kept a diary with entries for every day of that memorable year when the federal government moved from Philadelphia to the City of Washington. In a March entry she confessed that what she wrote was mostly

memorandums about her husband's life.(1) Indeed, as some historians read it, within the first month her entries proved that her husband designed both Law's and Tayloe's houses. That's quite a stretch. Read the diary:

Sunday

[January] 12th— A very fine day, as pleasant as a Spring day. After

breakfast Mr T. Peter called and mentioned that his wife was at home; we

therefore sent the Carriage for her. I, and Dr T— . accompanied them to

the Capitol, the General's and Mr Law's houses —the latter being locked

we entered by the kitchen Window and went all over it— It is a very

pleasant roomy house but the Oval drawing room is spoiled by the lowness

of the Ceiling, and two Niches, which destroy the shape of the Room.—

Mr and Mrs Peter dined with us and returned home early in the afternoon

some of her Children not being well.

C. M. Harris opines that "Thornton's role... is partially but substantially documented by his wife's diary for 1800." Certainly, that Thornton climbed through the kitchen window to get inside suggests he had some authority, though his touring with the Mrs. Law's sister might have given him sufficient license to do that. Pamela Scott puts it this way: "It was designed by William Thornton, and was 'a very pleasant roomy house' according to Anna Maria Thornton."(2)

Of course, as already pointed out, Mrs. Thornton criticized the house's oval room. Her husband likely informed Mrs. Thornton's criticism of the room. Thornton probably disliked Law's oval room because for years he had imagined his ovals under high domes. Fitting them into a five story townhouse was alien to his sensibilities.

Construction continued on Tayloe's house throughout 1800, but Mrs. Thornton only description of the house came on January 7:. According to her diary: "Tuesday [January] 7th, a beautiful clear day.... After dinner we walked to take a look at Mr. Tayloe's house which begins to make a handsome appearance." Harris counts that and the other seven walks in which they saw the house as evidence that Thornton kept tabs on the house he designed. In November, Thornton walked down to see chimney pieces imported from London. Harris credits Lovering for being the supervising architect but assumes that because of Thornton's experience as a commissioner and general knowledge of architecture, Tayloe and Lovering took his advice. Thanks to Thornton, the Octagon had a parapet. Since "two decorative" iron stoves came from Edinburgh and an artificial stone chimney piece came from London, Thornton must have been involved since he had been in both cities.(3)

Tayloe was educated in England and Lovering had worked there for many years. Harris also forgets that another commissioner, Gustavus Scott, had sterling reputation for having "a perfect Knowledge of the Value of Work & Materials." In December 1800, at her husband's urging, Mrs. Thornton went inside Tayloe's house to see the chimney piece. She inspected it accompanied by two lady friends. It was likely her first view inside the house. She wrote nothing about its interior, let alone that her husband designed it. Her diary also reveals that he had scouted a display of chimney pieces at Tunnicliff’s hotel back in May, evidently for the North Wing.(4)

Ridout found another entry in her diary that he thinks helps prove that Thornton designed the Octagon, but in that entry Tayloe's house is not mentioned. Ridout holds out the mere fact that Thornton designed another house in March 1800 as evidence that he did a design for Tayloe in 1797, 1798 or 1799: "while we were at breakfast a boy brought a note from Mr. Carroll of Duddington, (living in the City an original and large proprietor) requesting Dr. T- as he had promised, to give him some ideas for the plan of two houses he and his brother are going to begin immediately on Sq. 686 on the Capitol Hill."

Thornton spent the afternoon "drawing the plans for Mr. Carroll." He worked on the plans the next afternoon, and the next day, he brought Carroll home to show him the plans "with which he was much pleased." And that was that. That Thornton had a ready model for Carroll's two houses in the General's two houses, doesn't lessen the significance of his evident facility for a relatively complex house design. He was proud of what he had done for Carroll. On Sunday March 30, 1800, with a friend, the Thorntons "walked to see Mr. Carroll's houses."(5)

Ridout doesn't include another house Thornton designed in early 1800 as evidence that he had long been the community's ever ready house designer: "Saturday, Feby 1st a fine day. The ground covered with the deepest snow we have ever seen here (in 5 yrs.) - river frozen over. Dr. T- engaged in drawing at his plan for a House to build one day or another on Sq. 171." On February 4, 1800, she noted: "I began to copy on a larger scale the elevation and ground plan of the house."(6)

Of course, what she wrote in 1800 can be taken as an indication of what Thornton did in 1798 or 1799, but why treat the future as prologue when the diary actually tells a simple story. He didn't like Law's oval room. So he designed a house with better oval rooms. His wife thought Law's house roomy and Tayloe's wall handsome, so he showed her what a handsome and roomy house should look like. The large design with oval rooms in Thornton's papers does have something to do with the Octagon. The process that Ridout suggests happened sometime between April 1797 and May 1799 was actually reversed in 1800. After getting one of Lovering's preliminary plans, Thornton designed a house to rival Tayloe's.

She did not give any clue as to why Thornton designed the house, nor why he waited so long to design it. He had bought lots in that square in May 1797, a month after Tayloe bought his lot on Square 170. Thornton had bought several lots, 1 to 8 and 13 to 21, on the southern and eastern border of the square. He didn't own the lots 10 and 11 that were opposite Tayloe's lots on New York Avenue.(7) Judging from the topographical shading of an 1800 map of the city, the only sensible place to build was on lot 17 facing the President's house at the angled intersection of New York Avenue and 17th Street NW. That left Thornton with the same problem that the architect of the Octagon and Law's house had solved. That meant he could copy Lovering's solution and out do it with a nobler house.

His design for Lot 17 in Square 171 would not have worked on Lot 8 in Square 170. If situated there, the large oval room at the rear of Thornton's design would look out at the stables and yard where slave grooms could prove only to themselves that the master's horses loved them best. Thornton's design was an elaboration of Lovering's design for Tayloe. Thornton stretched its basic idea and added a larger oval room likely with a dome that mimicked his Grand Vestibule. Doing that was more in Thornton's character than paring down a design to suit Tayloe's needs. Not for nothing did he have his wife make a larger elevation of the house. Thanks to the slope of Square 171, the oval room at the rear of the house afforded a view of the Potomac River. The large semi-circular porch on the other side of the house invited eyes looking down from the President's house.

That explains the intended site of the design he drew in early February, but not the timing. In January 1800, Thornton was not necessarily looking for inspiration for a house of his own. He had a reason to check on Tayloe's house on January 7. As Mrs. Thornton noted in her diary, the board received a letter from Navy Secretary Stoddert reporting that the president planned to ship his furniture to the city in June. Mrs. Thornton didn't explain that the November 21 letter from White and Thornton and the December 13 letter from White prompted the president's announcement. Adams bristled at being told where he might have to stay and jumped to the conclusion that the commissioners wanted to park him in George Washington's Capitol Hill houses. He told Stoddert to tell the board that he insisted on moving into the President's house.(8)

White was not in the city on January 7. Evidently, he had not told his colleagues what he had written to the president. Commissioner Scott had not signed the November letter and assumed White had asked the president to choose a house to be rented. Scott dashed a letter off to Stoddert disavowing the very idea of not using the President’s house. Thornton also signed that letter. White would not take being accused of being dishonorable lightly.(9) The affair at least proved Cranch's 1797 description of Thornton as the vacillating commissioner.

Scott likely got Thornton to reveal what houses he and White had in mind. Scott had sold the lot to Tayloe and likely remained a friend. It bears remembering that before work began on the Octagon, Scott was having his own house built just north of the city. In 1807, master carpenter Andrew McDonald, "who finished the buildings on Rock Hill, near Georgetown, for the late Gustavus Scott, esq., now owned by William A. Washington; and also finished that elegant building belonging to Colonel John Tayloe..." offered his services again after retiring for four years.(10) Thornton had never built a house, let alone his own house. In January 1800, Scott likely knew that Tayloe's house would not be in a state to receive the president's furniture in June 1800. So, Thornton took a walk to see what state the house was in.

When Thornton battled Hallet, Hadfield and Hoban, he raised much rhetoric. He is not known to have said or written anything about his house on Square 171 that would rival Tayloe's. That does not prove that he didn't make a design. His wife was absolutely clear about that. But his writing nothing about it helps prove that Lovering designed Tayloe's and Law's houses. Thornton didn't have to attack him. Although "ingenious," Lovering was not a gentleman. Likely, in Thornton's mind, Lovering was not in the same league as an architect. The monumental, Roman Temple-ish exuberance of Thornton's house design proved that.

But why didn't Mrs. Thornton say more about such a consequential design? W. B. Bryan offered an interpretation for her lack of enthusiasm. She knew the house could not be built "owing, no doubt, to a lack of funds, which was a common experience in the life of a man who moved in a large orb, but one not within in the range of either the making or the saving money."(11) There is something to that, but whenever Thornton sold his Lancaster property, he expected to make $40,000. The death of his mother in October 1799 might have led to some reckoning of the Tortola estate with money coming to Thornton.(12)

Mrs. Thornton likely reacted negatively to the trappings of grandeur not evident in the floor plan but obvious in the elevation she copied. At the time, the President's house was on Thornton's mind. On January 20, Benjamin Stoddert wrote to Thornton castigating the commissioners for not properly preparing the President's house for the reception of the president: "A private gentleman preparing a residence for a friend would have done more than then has been done," Stoddert wrote and he wanted an enclosed garden "at the north side of the Presidents Houses" similar to one had by the richest man in Philadelphia, William Bingham. There also should be a stable, carriage house and garden house. The latter should be in a garden that would be "an agreeable place to walk in even this summer."

On January 30, Thornton wrote back that he had always been for grandeur throughout the city. His colleagues had always dragged their feet: "They are however afraid of encouraging any expense not absolutely necessary, and seem not to think these things necessary that you and I deem indispensable." He then reflected on the mansion: "Some affect to think the house and all that relates to it are upon too extravagant a scale. I think the whole very moderate,..." He added that the president should get a salary of $100,000 to maintain it. At that time he made $25,000. Thornton also sent a plan of the President's house to the president and noted that "the colonnade to the south is not completed at present, and temporary steps are to be put in." As a president looked south from his mansion, he would see lots Thornton owned at the east end of Square 171.(13) The day after he wrote that letter to Stoddert, he finished his design for Lot 17.

After living with her husband for ten years, Mrs. Thornton could distinguish the possible from the impossible. She also never described what Thornton was doing to his Capitol design, on which he worked during the two week after finishing his design for Square 171. On February 5: "Dr. T at work all day on the East Elevation of the Capitol. - I assisted a little till evening -." Again on February 7, "Dr. T was engaged in working at his plan of the Capitol." And again on February 9, he was "engaged on his plan of the Capitol." On February 14, "In the afternoon and evening drew on his plan of the Capitol." She could have provided details. She knew what had been built. On the afternoon of January 4, he took her and her mother to the Capitol where "we stayed for some time by a fire in a room where they were glazing windows while Dr. T-n laid out an oval round which is to be the communication to the Gallery of the Senate room."(14)

The January entry challenges the accepted narrative that Thornton left it to others supervise construction of the Capitol. The February entries challenge the idea that he had restored his design of the Capitol. If so, why was he still working on it in February 1800? But Thornton prided himself on having perfected a design that others could build without his making revisions or getting his hands dirty. Therefore, what the diary described were special cases. What he did was likely tied to the death of the General. Laying out the oval round brought him close to their collaboration now ended. Working on his design might have been necessitated by the need to accommodate the General's tomb under the dome.

Yet, the diary also makes it crystal clear that he did not wallow in unrealistic designs. Not only did he design a serviceable house for Carroll and his brother in March, he also designed a stables for Law in late February. On February 27, "Dr. T- received a note from Mr. Law enclosing a rough Sketch of a plan for a Stables & c. behind his house which is five stories before and three behind, which Dr. T- had promised to lay down for him as he had suggested the ideas - The Stables and Carriage house are to be built at the bottom of the lot and the whole yard to be covered over at one Story height, and gravelled over, so as to have a flat terrass from the Kitchen story all over the extremity of the lot.... Dr. T- engaged in the evening drawing Mr. Law's plan." And that was that. There is no more mention of the plan. It is not certain what Law built, but the boarding house would advertise its ability to board 60 horses.(15)

The demand for Thornton's architectural talents was short lived. Both Law and Daniel Carroll continued to build houses in a vain effort to profit off their many building lots in the city. Other men, including Hoban, designed their houses. There is no evidence that they again asked Thornton for building plans.(16) In February and March 1800, both Law and Carroll had a reason to flatter Thornton. Through her nephew William Cranch, who was then Law's lawyer, they likely learned that Mrs. Adams had doubts about moving into the President's house. She feared the building would be too green. Law wrote the letter to James Greenleaf, already quoted, that described his house and asked him to see that Mrs. Adams got the letter. Carroll sent a letter to Cranch describing his house, and Cranch sent it to her. With moving into Tayloe's house out of the question, that left Law's and Carroll's house in the running. Having Thornton on their side could do neither Law nor Carroll any harm. Coincidentally, Bishop John Carroll asked Thornton to submit a design for a new cathedral in Baltimore. He also asked other architects and eventually chose Latrobe's design.(17)

There was another reason to flatter Thornton. Law and Carroll had long been promoting the eastern side of the city. Despite his design of the Capitol, Thornton never became a familiar face on Capitol Hill. What better way to keep him focused on Capitol Hill than by involving him in other projects there. Then the federal government began moving into the city in June. Congress had already given cabinet officers money and power to prepare the city. The cabinet let navy secretary Stoddert disburse it. The House sent their doorkeeper Thomas Claxton to prepare their chamber and both the Senate and president relied on him.(18) The Constitution gave congress exclusive jurisdiction over the city and its public buildings. Commissioner Thornton became less important and it was widely thought that the board's days were numbered.

That reality combined with a slow realization that no payment from Tortola was coming in 1800 led to gloomy October thoughts on Mrs. Thornton's tenth wedding anniversary: "I hope we may be able to pass the next anniversary of it more agreeably! This time twelve months where shall we be? My husband has written this day to his father-in-law, desiring immediate remittances, for in consequences of Chorley's breaking, he is brought into difficulties, which after getting through, I hope he will never know again." Chorley was the agent in England for the family's sugar plantation.(19)

Care should be taken when interpreting Mrs. Thornton's take on her husband's designs. On the whole, she seemed to have little interest in or hope for them. In August, she mentioned a house plan for Lawrence Lewis but said nothing about it. She lost interest in his church for Bishop Carroll. Her diary showed much greater interest in her husband's enduring passion for breeding and racing thoroughbred horses.

On March 12, the day her husband got the note about designing a house for Daniel Carroll, she could put more portentous news in her diary: "a boy came from the farm with a 3 yr old Sorrel filly which Dr. T- has exchanged with Mr. Tayloe - He then wrote a note to Mr. O'Reilly to know when he can have his boy to go with Driver to Mr. Tayloe's." On March 13, she wrote:

Joe set off early this morning to accompany Randall Mr. O'Reilly's boy (whom Dr. T. engaged, letting Mr. O'R- have another during his absence) to stay at Mr. Tayloe's Mount Airy, Virginia, to train Driver. He also took the Sorrel filly; is to go as far as Neabsco near Dumfries and return to morrow. He rode one of the carriage mares. He took a letter from Mr. Tayloe to the manager of his iron works at Neabsco directing him to send a man with Randall to his seat. Took with them corn, bread and meat to save tavern expenses. After breakfast Dr. T went to the [commissioners'] office, I worked on my screen, mama quilting. Dr. T wrote a letter to Mr. Lewis, to request to him to purchase some provisions on account for the two asses he bought at Mt. Vernon because he could not make it convenient to send for them immediately.... Dr. T worked all day on Mr. Carroll's plans - I read-(20)

Joe Key and Randall were slaves. Randall was a jockey. Tayloe favored slaves as jockeys, which was congenial to Thornton. White jockeys who won races demanded more money.(20)

Mrs. Thornton never made a list of the houses Thornton designed. She did count their horses: "We have twenty-three horses - 17 at this time at the farm - one lent to Mr. Brent - one sent to Mr. Fitzhugh to keep on shares - Clifden now here to be sent to Mr. Sam Ringgold - Driver now at the farm to be sent to Mr. Tayloe's in Virginia to run."

Back in January, Thornton had met Tayloe one evening at the Union Tavern in Georgetown. The latter had to get an early start for Annapolis in the morning so, given the winter darkness, they had no time to see his house under construction. In Annapolis, he graciously helped determine the legal status of property in Georgetown owned by her husband's sister-in-law who lived in the Virgin Islands.(21)

Thornton's long friendship with Tayloe gives credence to the assumption that he must have relied on Thornton for architectural advice. After her diary, Mrs. Thornton kept notebooks listing social occasions from 1802 through 1815. Thanks to that, one can gauge the comings and goings of the Tayloes. However, judging from her 1800 diary, Tayloe was in the city for one day. It's hard to believe that he avoided the city while his house was being built. She still noted their infrequent visits to "Tayloe's house." She noted that her husband went to the Alexandria races in November. She also noted who he met there. She didn't mention Tayloe. In a newspaper ad, offering horses for sale, Tayloe said it was "probable" that he'd be there. In her 1802 notebook, the frequency of visits between the two families was not out of ordinary during the city's intense social season. It took a few years before her notebooks give the impression that the two families depended on each other as friends.

Still, her 1800 diary begins to mark out a deepening relationship. Trading horses and helping with legal problems were good starts even if Thornton and Tayloe only saw each other briefly one evening in January. Her diary also notes the beginning of Thornton's need to rival Tayloe, not only in regards to houses, but also on the turf.

On June 18, 1800, she wrote: "Driver returned from Virginia in the afternoon lame and in bad plight." Evidently there had been no letter from Tayloe warning them of this. For the rest of the year, she did not note any more letters from or to Tayloe. There was no more mention of trading or training horses with him. She did not mention her husband's reaction to Driver's bad plight.(22)

Almost two years after Driver's return, Thornton made his reaction public. On April 5, 1802, a very long ad in the National Intelligencer gave his version. The ad was cast as a traditional offer of stud services, but it broke the mold by touting races that Driver lost:

Driver was never tried but once, by John Tayloe, esq., at Tappanoe in Virginia when the bets were in favor of the winner (Yaricot) distancing the field; but Driver lost one heat by only a few feet, and the other heat by only four inches, in three mile heats, distancing the other horses; which as Driver, like his celebrated sire, is a four mile horse, was thought a great race, especially as he was much out of order in consequence of a bad cough. Col. Holmes [probably Hoomes] told me he was thought by those who saw him run, one of the best bottomed horses in America, or perhaps in the world. Driver was put into training the last autumn, but met with an accident that prevented his starting; however, he proved one of the fleetest horses Mr. Duvall ever trained, and of ever lasting bottom.

By "bottom" was meant staying power and stamina. While the ad didn't blame Tayloe for sending Driver home in "bad plight," later in the ad, Thornton quoted Charles Duvall as saying: "if I had trained him at four years old, I think he would have made the best horse on the continent...." Which is to say, if Thornton had sent Driver to Duvall instead of Tayloe, then in 1800 Driver would have shined in the Washington races in 1801, where, by the way, in three races, each with two heats, Tayloe's horses came in second, second and third. Thornton didn't share Tayloe's opinion of Driver. Maybe he never asked for it.

The rest of the ad also put Tayloe in his place. It celebrated Thornton's English connections when everyone knew that Tayloe's connections were unparalleled. Thornton wrote: "the dam of Driver was purchased by my relation Isaac Pickering, esq., of Foxlease, Hampshire, England, who sent her to the Earl of Egremont's by one of his own grooms." Tayloe knew the earl well. He would soon buy a farm outside the City of Washington and name it Petworth after the earl's seat in England. Thanks to Driver's pedigree, Thornton could drop the names of two lords and a duke. No reader would mistake mere name dropping as indicating a personal acquaintance, but the ad gave the impression that only the Atlantic Ocean kept Thornton and the earl from being best of friends. Thornton added that Driver's pedigree was certified by Governor Ogle, who was Tayloe's father-in-law.(23)

Merely by importing horses, Thornton became Tayloe's rival and how much friendship tempers such rivalry is an interesting question. Even bitter foes shake hands after giving their all in the arena. There is no evidence that Tayloe reacted to the insinuations in Thornton's ad offering Driver's services. But if one is going to suggest that Thornton did more than draw a design, that he bothered with stoves and chimney pieces, or, as Glenn Brown implies, designed every cornice, then one has to explain why Thornton took the gloves off, so to speak, to defend his relatively untried horse just as the finishing touches were put on Tayloe's house. In April, about the time Thornton vindicated Driver, Dorsey closed his books on the project, paying Lovering $900 for his services.(24)

Likely because Tayloe knew that every horse breeder in America was envious of him, Thornton's envy made no difference to him. New to the federal city, he was looking for friends, not rivals. He had not won election to the House. Not elected, not appointed, and not heavily invested, Tayloe had no reason to be in the city. He had nothing better to do than to be sociable and be of service. His closest friend in the city, Congressman John Randolph of Roanoke, was his arch rival on the turf. He had a biting wit and trigger-ready sense of honor. Tayloe maintained a long friendship. There is also no evidence that Tayloe ever lost his liking and respect for Thornton.(25)

After the ad about Driver ran, Tayloe may have also given Thornton an immediate leg up in the breeding business. In the spring of 1803, an ad offering the services of Wild Medley ran in the Washington Federalist. It noted that the horse was bought in Virginia by "W. Thornton." That was the only mention of the owner. The ad included a testimony signed by John Tayloe certifying the wonders of a filly got by Wild Medley that handily beat Tayloe's horse. Thornton owned Wild Medley until it died in 1810.(26)

Of course, it was evident to everyone else that they weren't equals. They were poles apart. Tayloe relied on an enormous stable to find the horse to cross the finish line first. Thornton propelled his chosen horse with rhetoric. As for the social aspects, even in the local jockey club, Thornton found a niche rather below Tayloe's. There is no evidence that he was involved in the December 1802 Jockey Club races. Tayloe certified the results. Thornton was not mentioned as an officer or contestant. In the third day's race, James Hoban's Potatoes, a four year old got by Tayloe's Lamplighter, won the first heat. In 1806, Thornton was not one of the club's six officers listed under President Tayloe. Jockey Club purses relied on the offerings of Jockey Club members and Thornton was often short of ready cash. He hosted a dinner for members, and, as his wife noted, he contributed sweat by inspecting the racing grounds in the early morning.(27)

Although he would never skimp in setting his wardrobe, he lacked the polish of his adopted class and could let anger and calculation break a noble pose. Thornton's and Tayloe's principal slaves, Joe Key and Archy Nash, were often noted by Mrs. Thornton as heading off together to do their errands for their masters. Tayloe's will freed Nash and instructed that he be give $100 a year. Thornton's will didn't free any of his slaves. In 1808, he had sold Joe Key to a North Carolina congressman. Key must have done something wrong because Thornton had to pay his jail expenses. On his way south, Key escaped in Alexandria. A runaway ad did not lead to his return. In 1812, when he was found on the farm next to Thornton's farm, Thornton sold him again. Tayloe owned 500 slaves and used runaway ads when one escaped, but he never proclaimed that ending slavery was his life's mission.(28)

Thornton assumed that major victories on the track would come soon, but they didn’t. When they didn't, he still found a way to boast that his horse was better than Tayloe's. After the 1811 races, just as he had to explain Driver's falling short, he had to rescue Eclipse Herod's reputation. He wrote an advertisement about the horse. After explaining the loss in Washington as the fault of an overweight jockey, Thornton gloried in what the horse did next which included beating "Mr. Griffith's mare from Virginia raised by Col. John Tayloe..."(29)

That Thornton singled out a nameless mare vanquished by Eclipse Herod as having been raised by Tayloe goes beyond the usual niceties of identification. Friends can be rivals, but what is the point in competing in such a petty way with a close friend and the richest and most successful horse breeder in America? Tayloe didn't seem to notice, and they shared the turf in other ways. On November 14, 1811, Thornton sent 40 ewes to Petworth, and 20 more the next day. Thornton's enthusiasm at that time was raising Merino sheep.(30)

Tayloe remained his arch rival. In the fall of 1821, Thornton bought Rattler a prize horse reputed as being able to beat any horse in the country. But it lost at that year's Washington Jockey Club Races. Thornton tried to save face the day after the race. The National Intelligencer published a report that:

The celebrated horse Rattler acknowledged by the best judges in Virginia, where he was bred and ran with so much success, to be the finest young horse of his day, having lost his race yesterday, after winning in great style at Annapolis the last week, it was thought proper to publish an examination made by the Judges which is given below: "We have examined Dr. Thornton's horse Rattler and found his near fore postern joint swelled, and the main sinew much enlarged and swelled, so as to render him quite lame."...(31)

After he bought Rattler, Thornton didn't pay for the horse. That dispute over $3,000 and the horse's condition was argued before the US Supreme Court which sent it back to the District court and eventual settlement after Thornton died in 1828. Thornton's motive for buying was on the record. The seller "declared" the horse to be "capable of beating any horse in the United States" and "recommended the purchasers to match him against a celebrated race horse in New-York called Eclipse." Thornton lost the race in Washington the day after Lady Lightfoot lost to Eclipse at the Union Course on Long Island. She was the pride of the South bred by Tayloe and she had a 31 race winning streak. A victory by Rattler in Washington might have assured a match race with Eclipse and Thornton's horse could have saved the reputation of Southern horses.(32)

In 1822, a broadside advertised "Rattler belonging to Dr. Thornton" as a stud. Tayloe actually bred the horse, but Thornton highlighted his pedigree in a way Tayloe never did. The broadside described the horse "as the best on the continent," equaling Tayloe's Sir Archy. Not only was Rattler gotten by Sir Archy but Rattler's dam Robin Red-Breast traced her pedigree back to old Highflyer just as Sir Archy did. Ergo, Rattler's pedigree was better that Sir Archy's because of a "double cross... Rattler is doubly descended from old Highflyer."

|

| 162. the Rattler broadside |

Deducing that Thornton did not design Tayloe's house based on his attitude toward Tayloe's breeding and management of thoroughbred race horses may seem like a stretch. But Ridout cites their mutual interest in horses as evidence of their mutual interest in the design of Tayloe's house. To be sure, patrons and architects are not bound to mutually admire each other. But when both the patron and the architect are gentleman, it would seem that they could manage appearances better than Thornton did. On the other hand, even gentleman architects can be hard driving and fiercely competitive, but at the same time, they are likely not to be so shy as to never claim credit for their designs.

In the summer of 1811, Thornton became very ill and his death was expected. Mrs. Thornton noted when Tayloe came to F Street to visit his friend and also offer him remedies. Tayloe no longer spent the hot months at Mount Airy. He had worked himself into the fabric of Washington's commercial life and did much charitable work. He even asked President Madison for a job. He wanted to be like Thornton, but draw no pay, of course.(33)

By 1811, few thought of Thornton as an architect. In 1802, President Jefferson and Madison had fulfilled their obligations to their one-of-a-kind friend by making him the State Department clerk solely charged with registering patents. Thornton took a $200 cut in salary to $1400 but recognized advantages to his new position. By 1811, he was using it to try to leverage some money out of Robert Fulton and his company. Thornton felt his work with Fitch in 1789 entitled him to steamboat royalties. Fitch had committed suicide in 1798. At the same time, an ill-fated gold company that he organized in 1806 shortly after news that gold nuggets were found in North Carolina made him the target of lawsuits. It was not the only vexation that threatened him with bankruptcy. He had to sell his house in Lancaster, England to cover his own and other debts he had secured. He feared that an adverse judgment in a libel suit filed by Benjamin Latrobe would cost him $10,000. The next chapter will examine what light his feud with that architect cast on his claims in regards to the Capitol design.

As he rallied from his illness, he managed to write a letter to Madison. The letter was all about thoroughbreds.(34) Madison had used Thornton's breeding services. When Madison returned from his annual vacation in Virginia, he invited Thornton and Tayloe to dinner at the President's house. The talk likely drifted from studs to the horse militia. Given up for dead, once he recovered Thornton showed no sign of moderating his ambitions. He soon set out to rival both Tayloe and Madison with boasts that require analysis. They proved that he didn't design the Octagon.

In 1811, Thornton was elected a captain in the Columbia Dragoons, a horse militia. Then in 1813, to his shock, the selection of a major was made by having two longer serving captains draw lots. In response, Thornton came up with a plan to improve his position in the militia and with the president. He wrote to Tayloe who was the colonel of the horse militia. Thornton asked him to persuade the president to become the "Commander in Chief of this District, in the same manner as the Governors of States." If he did, he would have to appoint aides to carry out his orders. In states, two aides came from the militia. It was not unknown for such aides to be given the rank of colonel.

Thornton had already broached the subject with the president who pointed out that none of his predecessors took command of the local militia. In his June 8, 1813, letter to Tayloe, he warned him of the president's "extreme modesty & unobtrusive Delicacy" and urged Tayloe to explain to him that "...Reason may require her votaries to walk in a line untrodden." Then he pleaded his case: "...if the president should consider the manner in which I have been treated, from a gentleman of his feeling, my case would claim from him some attention, and I know not of any way now to repair that breach of correct military conduct toward me except by such an appointment...."

What Tayloe or the president thought of Thornton's letter is not known. The letter wound up in Madison's papers so evidently Tayloe gave it to him. If she saw it, Mrs. Madison might not have been been pleased. As a last thought on the matter. Thornton opined that “Mrs. Madison would perhaps wish her Son to be the other [aide]; which would not only give him rank, but exempt him from common militia duty.”(35) Her 23 year old son went to Europe with peace negotiators. The president did not claim command of the District's militia and Thornton remained a major.

When the British army came close to the capital, Thornton was briefly called to active service, but he was not called up for the Battle of Bladensburg. He fled to Georgetown as the British invaded and burned government property. Then at breakfast the next day, he heard that the British were still burning government buildings. Clerks had removed the papers in his office for safe keeping, but not the models of inventions. He was especially concerned about a musical instrument that he invented and hired a man to build. It had "68 Strings which by Keys in the manner of the piano Forte, will give all the tones of the violin—violincello—bass—double bass &c—...."(36) As he put it in a letter to the National Intelligencer that he wrote a few days later: "I was desirous not only of saving an instrument that had cost me great labor, but of preserving if possible the building and all the models."

Thornton's

story of how he saved the Patent Offices still resonates with

historians. His plea to British officers is often quoted: the building

"contained hundreds of models of the arts, and that it would be

impossible to remove them, and to burn what would be useful to all

mankind, would be as barbarous as formerly to burn the Alexandrian

Library, for which the Turks have been ever since condemned by all

enlightened nations." (An August 30 article in a Georgetown newspaper

characterized the speech differently: "...the cause of general science

would suffer by its conflagration.")(37)

Thornton did much more. On August 26, he found that, save for some of their wounded, the British army had gone. He called on the mayor and found that he had gone. He soon realized that he was the only justice of the peace in the city. Acting in that capacity, he claimed that he organized a guard for the President's house, Capitol and Navy Yard. He later wrote that at the Navy Yard, "I went and ordered the gates to be shut, and stopped every plunderer." He ordered provisions for the wounded: "I appointed a Commissary, and ordered every thing that the Doctor thought requisite, for which I would be responsible. The [British] Sergeant requested my protection for all his men. I told him they would be protected;... He promised to obey every order. I gave orders and he fulfilled them. Some stragglers, I understand, were taken up, and perfect order kept throughout the city."(38)

After restoring domestic tranquility, Thornton reacted to the rumored return of the enemy on ships coming up the Potomac. Thornton decided that a "deputation" should be sent to the British. In her diary, Mrs. Thornton wrote: "The people are violently irritated at the thought of our attempting to make any more futile resistance." The president, secretary of state and attorney general returned to the city on the 27th. On the 28th they rode to the Navy Yard. Thornton followed them. Secretary of State Monroe had seen service as an officer during the Revolutionary War and the president intended to make him secretary of war. In the meantime, he placed him in command of military operations. In a letter he wrote to his son-in-law on September 7, Monroe recalled: "...we were followed by Dr. Thornton who stated to the president that the people of the city were disposed to capitulate. The President forbade it. He pressed the idea as a right in the people, notwithstanding the presence of the govt. I turnd to him, and declard, that, having the military command, if I saw any of them, proceeding to the enemy, I would bayonet them. This put an end to the project. The doctor retird, and afterwards changd his tone."(39)

Thornton took Monroe's threat very seriously. In her diary, Mrs. Thornton wrote that to defend the city, her husband "distressed us more than ever by taking his sword and going out to call the people...." Alexandria capitulated, the British ships resupplied and then sailed back down the Potomac. Thornton sheathed his sword, and obeyed orders to remove models from the Patent Office so congress could assemble there.

Dolley Madison's sister and her husband Richard Cutts lived next door to the Thorntons. On September 8, Mrs. Thornton visited the ladies: "I had long conversation with Mrs. Cutts and Madison today. They have listened to many misrepresentations and falsehoods concerning Dr. T_ and of course are not pleased with him." The day before Thornton's defense had been published.

He explained that he never urged capitulation. He had wanted to remind the British "that it was understood when their army destroyed the public buildings and property no other would be molested, and to request therefore they would not permit their sailors to land." He made no mention of the threat of a bayonet in the back, nor his novel theory that the "the people" had a right to surrender the city even if the government had returned to the city.(40)

In his letter, Thornton contrasted his usefulness with the mayor who had fled and did nothing. That opened the pages of the newspaper to a response from Mayor Dr. James Blake who accused Thornton of collaborating with the British. He even gave a key to his office to a British officer. Blake also recalled that before the battle Thornton had opined that he was "opposed to the war, and would not give a cent toward carrying it on."

In his reply, Thornton mocked Blake as a mere tax collector and made a stanza of doggerel in which "Blake" rhymed with "snake." The editor wrote at the bottom of the letter "The Public and the editor conceive that this sort of BADINAGE to be unsuited to the times and expect it to cease." Thornton didn't deny that he was against the war. He was "a man of peace," and his "situation has nothing to do with politics or war, being a member of the great Republic of Letters, and considering it a duty to labor for the happiness of all mankind." Blake replied to Thornton's second letter that he also was seen "privately communicating with a British officer of distinction." Blake concluded "Doctor T has been living upon the Public Treasury for near twenty years, and I dare say he cannot point to a single service that entitles him to the patronage of the government."(41)

The Madisons moved into the Octagon house on September 8. During the British incursion, Col. Tayloe had been in active service down the Potomac on the Virginia side primarily delivering dispatches. The last was put into Monroe's hand at 2 am August 27. Judging from a detailed diary Mrs. Thornton kept then, Tayloe had no contact with Thornton. She only mentions that he was a nearby hotel recovering from illness. Thornton was more intent on visiting a wounded British colonel named William Thornton. In some versions of the burning of the capital, Thornton not only gets credit for his noble defense of the Patent Office but also for designing the house into which President Madison moved when he returned to the city. Those versions leave one with a warm feeling for the gratitude the Madisons must have felt for Thornton for his designing the house where they lived for six months in such special circumstances. However, Thornton had had nothing to do with the Octagon. Mrs. Thornton's never alluded to it in the detailed diary which she kept during the crisis. Later, in her notebook, she mentioned going to Mrs. Madison's "drawing room," but didn't note where it was.(42)

Thornton seemed to have enjoyed the remainder of the war vicariously, but not with an intrepid American dragoon in mind. The high British officer that Thornton had visited after the burning of Washington was Col. William Thornton. In June 1815, Thornton wrote to Col. Thornton who had recovered in time to fight in the Battle of New Orleans. Thornton gushed over the colonel's gallantry and discussed European politics. He closed with the happy report that the buildings the British burned would be rebuilt, and that efforts to move the nation's capital elsewhere failed. He took credit for that: "they now would have succeeded if I had not prevailed on Major Waters and Col. Jones to spare the Patent Office containing the Museum of the Arts, which temporarily accommodates the Congress. Thus it was observed one William Thornton took the city, and another preserved it by that single act." He couldn't also claim that he designed the house which temporarily accommodated the president.(43)

|

| Colonel William Thornton |

When her husband's second term ended in March 1817, Dolley Madison made farewell visits to all her friends in the city, but not to Mrs. Thornton. She was devastated. Thornton noted the slight in a letter to Madison and added, " I have long had to lament a marked distance and coldness towards me, for which I cannot account."(44)

1. Mrs. Thornton's Diary p. 113.

2. Scott, Creating Capitol Hill, p. 129; Harris p. 586

3. Diary, pp. 92, 217; Harris, p. 585,

4. Diary, pp. 217, 141.

5. Ridout, Building the Octagon, pp. 29-30, 61.

6. Mrs. Thornton’s Diary, p. 102.

7. National Intelligencer 4 July 1820 "Marshal's sale."

8. Stoddert to Commrs., 3 January 1800, Commrs. records.

9. Commrs to Adams, 7 January 1800, Commrs. records; White to Adams, 15 January 1800.

10. Washington Federalist, 28 February 1807 p. 3.

11. Bryan, History of National Capital, vol. 1, p. 346.

12. WT to Madison, 2 September 1823.

13. Stoddert to WT, 20 January 1800, WT to Stoddert, 30 January 1800, Harris p. 532-3.

14. Diary, pp 90-1, 102-4, 106.

15. Mrs. Thornton's Diary pp. 107, 108, 112. National Intelligencer 5 January 1801, "Conrad and McMunn" ad, p. 4

16. Scott, Creating Capitol Hill, p. 116.

17. Mrs. J. Q. Adams to John Adams, 22 November1820, Founders online; A. Adams to Cranch, 4 February 1800 footnote 3, Founders online; Law to Greenleaf, 9 April 1800, Adams Papers: Cranch to A. Adams, 24 April 1800; see also Abigail Adams to Anna Greenleaf Cranch, 17 April 1800, Adams Family Papers.

18. Thomas Claxton to John Adams, 3 November 1800

19. Mrs. Thornton's diary, 13 October 1800, pp200-1.

20. Diary, pp. 116-7; Cohen pp. 117-8, already cited in Chapter Ten.

21. Diary p. 107

22. Diary pp. 157, 209; Washington Federalist 1 November 1800 p 1.

23. National Intelligencer 5 April 1802 p. 3.

24. Ridout, Building the Octagon, p. 92

25. Virginia Argus 5 May 1801, Tayloe lost to Taliaferro 400 to 707; B. O. Tayloe, In Memoriam

26.Washington Federalist, 29 April 1803 p. 4; Mrs. Thornton's notebook 1807 vol. 3, image 2

27. Washington Federalist 8 December 1802, p. 1; Clark, "The Mayoralty of Robert Brent." Journal of Columbia Historical Soc. 33/34 pp. 283, 288-290.

28. Wikitree Tayloe; Mrs. Thornton's notebooks vol 3 Image 38, 75, 141 (for sale of another slave); National Intelligencer. ad dated 16 May 1808)

29. American Turf Register, vol. 4 p. 391-2.

30. AMT notebooks, vol. 3

31. Rattler Broadside, downloaded but unsourced.

32. Thornton v. Wynn 25 US 183; Thornton v. The Bank of Washington.

33. Tayloe to Madison, 16 July 1809

34. WT to Madison, 3 August 1811

35. Clark, "Dr. and Mrs. Thornton", p. 182; Thornton to Tayloe, 8 June 1813 Madison Papers LOC

36. WT to Jefferson, 27 June 1814; several sources claim that WT helped his clerk pack and move the papers to his farm. In her diary she did not mention that nor did WT in his report on what he did at the time.

37. Georgetown Federal Republican 30 August 1814 p. 3

38. National Intelligencer 7 September 1814.

39. Journal of Columbia Historical Society, 1916, "Mrs. Thornton's Diary: Capture of Washington" pp. 177-8, 181; Monroe to Hay, 7 September 1814, Papers of James Monroe, University of Mary Washington.

40. op. cit.

41. September 10, 1814 on-line copy at Dobyns; Natl. Intelligencer, 13 & 15 September 1814.

42. American State Papers, Military Affairs vol. 1, p. 569; Howard, Hugh, Mr. and Mrs. Madison's War, p. 253;

43. WT to Col. WT, 24 June 1815, Gilder Lehrman Institute.

44. WT to Madison 3 March 1817, Founders online

American State Papers, Military Affairs vol. 1, p. 569

Comments

Post a Comment