Chapter 15: On the Heights of Mount Chimborazo

Chapter Fifteen: On the heights of Mount Chimborazo

|

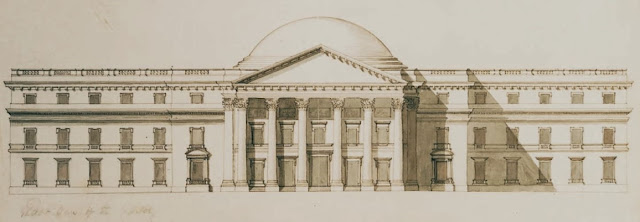

| 198. Capitol 1832 |

In his feud with Latrobe, Thornton defended his character by citing his presidential appointments to positions of trust, and that should not be taken lightly. That he was a commissioner of public buildings lends credence to his claim in 1805, and still made today, that General Washington told him to restore his original design made in 1793. That he was Superintendent of the Patent Office lends credence to his claim that he invented the steamboat in 1789. That he held positions of trust led to his opinions on public issues being trusted. When he died, contemporaries did not mention the Capitol, where Bulfinch had designed and supervised completion of the dome, but they remembered the offices Thornton had held: "During the first Administration, he was introduced to President Washington, whose regard he conciliated, and by whom, having been appointed a Commissioner for laying out this Metropolis, and fixing his future residence here, he may be considered one of its founders. As soon as the Patent Office in the State Department became established in Washington, he was invited to preside over its important duties, a function, which during four successive administrations, he has ably fulfilled...."(1)

In "The Administration and Reform of the U. S. Patent Office, 1790-1836," Daniel Preston gives a glowing account of Thornton's tenure. Preston blames the flawed patent laws, a niggardly congress that gave the director little money, and the cupidity of too many American inventors as the roots of any evils. He alludes to Thornton's frustration and quotes Senator William Plumer's 1807 observation of Thornton's messy office: "...a little money and labor would remedy the problem." However, Preston doesn't complete the quote. Plumer added: Thornton "has too long been guilty of great negligence."(2)

Of course, whether Thornton mastered or made a mess of the Patent Office, both paths would take an equal amount of time, 9 to 3 every working day, and distract him from architecture. In that respect, it shines no light on his previous architectural work save that it prevented him from designing another monumental building or house that would reaffirm his genius.

But what if Latrobe was right, that "official intrigue from Poverty" led to "incorrect impecuniary conduct," that combined with his "vanity" to make him a "Madman?" Even his wife admitted that the sum of his somewhat shady dealings led to profound disappointment. If so, then how did he redeem himself?

Four months after her husband's death, she was struggling to pay off his many debts. The executors of his estate sold his stable. The advertisement for the sale ran nationwide. Rattler wound up in Kentucky. Thornton's last boss, Secretary of State Henry Clay, almost bought him and did buy the Dutchess of Marlborough for $500. His city lots found no immediate buyers. She got $500 down on a small farm they owned in what would become the Mt. Pleasant neighborhood. She found buyers for 20,000 bricks salvaged from a house Thornton had evidently financed but was pulled down before it was finished. So much for assets, then she faced his personal debts and tortured relationships with all the area's banks. She found an old begging letter he wrote to a relative after a check bounced because the English agent for the Tortola plantation failed. She reacted in the diary she began writing in May 1828:

Oh my god how unfortunate he was - always involved in losses and disappointments, by the failure and dishonesty of others, he became plunged from one difficulty to another - and his mind accustomed to lawsuits, debt and all its dreadful consequences. His heart was good, his feelings good, his principles good, and yet circumstances which in many cases he could not control, (tho' I acknowledge in some he was imprudent and led away by the plausible representations and smooth faced deception of others) made it appear that he was in-different in his pecuniary transactions to those principles of honor and strict propriety which ought always be adhered to by a man of honesty and correct education But the Almighty judges the heart he sees into its recesses. His some errors of judgment. His life one of disappointment in many ways.(3)

Twenty years earlier, he wrote to his boss James Madison to explain how a lawsuit forced him to escape to his farm to avoid being jailed. He explained that he had gotten no money from Tortola in 1807 and 1808. He reminded Madison that he had secured Blodget's $10,000 bail. Blodget's plight was notorious. A judge had ruled that Blodget had to pay $21,000 to the winner of the Hotel Lottery. That was the amount of money needed to finish the hotel. Bail allowed Blodget to join Thornton for dinner at F Street and layout the Senate for an impeachment trial but not venture much further. Around 1806, when he did, Thornton was liable for the bail as well as Blodget's debts. To pay off his debts, Thornton told Madison, he sold his Lancaster, England, property for $20,000, "which discharges a large portion." He didn't pinpoint his current trouble. Payments for gold company lands in North Carolina were overdue. His mother-in-law paid his bail to keep him out of jail. Thornton closed the letter arguing for a raise at the Patent Office and also bemoaning his fate: "I am unwell in body and mind."(4)

Latrobe was suggesting that no matter his office, Thornton's principal mission was to exalt Thornton. He remained the vain architect of his own fame. He lied about his patent claims, especially regarding the steamboat, in the same way that he lied about architectural claims, especially regarding the Capitol. Poverty justified his exaggerations. Perched in the Patent Office, he could peck away at selected inventors' profits. When challenged, his cited the First Amendment right of free speech and his low salary.Then, in 1821, he dismissed his job at the Patent Office as "trivial" and begged to be sent on a mission to aid South American revolutionaries. For the remainder of his life, that consumed his imagination and, to the degree that those worthies visited him, his wine. He did trumpet their cause. His 1828 eulogist lauded him: "His benevolence expanding into philanthropy, was active and boundless. Witness the early, eager, and disinterested efforts of argument and eloquence which are embodied in his memorials, some of which preceded public opinion, and probably contributed to incline its tardy prudence in favor of Greek liberty and South American independence."

Thornton craved more. He wanted the president to place him in the van, on the scene, a fount of strategy and schemes. His eulogist tried to capture the flame that burned in Thornton's soul: "His love of knowledge was great; his love of liberty greater; but his greatest love was that of truth. Truth he incessantly sought, through every avenue of science or literature, and fearlessly pursued through the whole course of his career with unabated ardor...."

The patent system, as designed by congress, seemed designed to be the least frustrating chapter in an inventor's life. A patent applicant swore that he or she had been an American citizen for the last two years, and that the invention was novel or improved an existing invention. The application included a written description of the invention as well as drawings and a working model if its size permitted and a $30 fee. Patent clerk Thornton would send the fee to the Treasury, and copy the description of the patent in what was called a schedule. Then he would write out a certificate signifying that the inventor had a patent which would be the case once the president and secretary of state signed the certificate. The inventor could then license others to use the invention in return for a royalty. By suing in federal court, the inventor could preserve his rights for 14 years.

Despite the law not requiring his opinion of an invention, Thornton felt obliged to point out to applicants when their invention was not novel. He also pointed it out to everybody else. When Thornton found some value in an application, he tried to make it better. When he was able to improve the application, he wanted the inventor to share profits arising from the invention. He understood that he was able tonhelp not because of his wide experience but because of his understanding of the underlying scientific principles. He was biased toward the primacy of the idea, and he did not forget his own. Thus anyone who realized Thornton's ideas by making an invention did not invalidate Thornton's claim that he was the true inventor. Convinced that he was making the invention better, he did not hide what he did or his intent, which could exasperate his wife.

For example, in her 1808 notebook for August 6, Mrs. Thornton jotted down: "The Hawkins won't stand to their agreement and are very angry at not getting their patent." Their agreement is not extant. While being investigated by congress in 1811, Thornton denied ever taking extra fees from applicants. That suggests that Thornton angled for a share of future profits based on ideas he shared with the Hawkins brothers.(5)

Thornton's idealization of the patent process resonates with historians since it better approximates the modern patent process which enshrines what is now called intellectual property. In 1819, two days after a newspaper announced that an army board of officers had approved John H. Hall's breech loading rife, it announced three days later: "We are now informed that the rifle was originally invented by Dr. William Thornton...." A letter giving the details of Thornton's claim relied on the testimony of his clerks. Hall responded: "I would now ask, why does the Dr. have recourse to such writings from such men, for identifying the plan of his gun with the plan of mine, when, by producing the gun itself, and the drawings of which he speaks, and having them compared with my gun, by competent judges, the question of right may be decided at once."(6)

Addressing the dispute with Hall, Daniel Preston accords Thornton a specie of droit de seignure: "This was a classic case of conflict between gentleman inventor without the means to implement his design and the craftsman who had the skill and knowledge to manufacture the invention. Without question Thornton was less than graceful in his refusal to yield the right to Hall. But he did have a valid claim to the invention - he was not a vulture preying on poor unsuspecting craftsmen."

Actually, he was. That he claimed he invented the rifle before Hall did was but half his imposition. He issued a joint patent for the rifle and then tried to stop Hall from manufacturing it himself. Thornton insisted on only licensing the patent so whoever made the rifle had to pay royalties.(7)

Thornton refused to accept that anyone who had the same idea could really know more about it merely because they actually built it. Thornton turned the patenting process that required virtually no judgment on his part into a way to thwart rivals and profit from their inventions. By doing so under the guise of pursuing truth, he won the affection of the public whose default reaction to new inventions claiming monopoly rights for 14 years was that there some trickery involved. At the same time, he turned a bureau for the protection of inventors into a museum open to everyone. Once congress authorized Latrobe to fashion a large Patent Office in a corner of Blodget's Hotel and also gave Thornton money to hire a clerk and a workman, he filled his office with patent models and other inventions. With his capacious memory, Thornton became a clearing house of information about inventions and techniques. A series of letters between Thornton and Jefferson after the latter's retirement and before he devoted most of his time to his university project gives an impressive display of Thornton's grasp of inventions.(7A) It behooved an unknown inventor to become known by Thornton.

Thornton took time to refine his grift. At first, he simply tried to destroy a rival's reputation. In December 1804, Senator John Quincy Adams checked on a constituent's patent application. Adams wrote in his diary that Thornton explained that "he thought it not a new invention— Which indeed he says is the case of almost all the applications for Patents— And others are for things impossible." To Adams, Thornton gave an example of a fraudulent invention "by a Clergyman of Bordentown, New-Jersey, named Burgess Allison, who has a patent for improving Spirits by filtration through charcoal, which had been known and practised for many years—"

Actually, Allison was not a fraud. He was a rival. He had two patents on ways to improve spirits by filtering. Thornton was interested in the same topic. In 1809, he got a patent on "modes of ameliorating spirits and wine." Allison had been elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1789. By the end of 1804, Allison had four patents including two on improving spirits. He proved to be more successful as an inventor than Thornton. In 1813, Jefferson lauded Allison's loom.(8) The Hawkins brothers' invention made carbonated water and that too was too telling an advance on processes that Thornton had also cast his thoughts. But in their case, Thornton merely angled for their profits.

In late 1806, Robert Fulton came to Washington to promote his concept of "torpedo warfare." He excited politicians, including the president, and distressed naval officers. Meanwhile, his steamboat was being built in New York City, backed by the wealthy Livingston family. He had learned about steam engines in England and had built a prototype steamboats in Paris in 1803 when Robert Livingston was the American ambassador there. He obviously wanted to meet the head of the Patent Office. He and Thornton spent New Year's day together and socialized whenever Fulton was in town. It wasn't until a year after the first successful voyage of his steamboat that Fulton set out to get a federal patent.(9)

Fulton's

business strategy was the same as Fitch's: get monopoly rights and

patents from states for steamboat service on their rivers. Fitch got

monopoly rights from New York State in 1787, and then a federal patent

in 1791 but so did his rival inventors. He died by suicide in 1798, and

his patents expired in 1805. Then the Fulton company got monopoly rights

in New York in 1803, pending a successful voyage of a steamboat. In

1808, after his steamboat averaged 4 miles an hour in its maiden

voyage from New York City to Albany in the summer of 1807, a monopoly

for up to 30 years was finalized depending on the number of boats put in

service. It offered more protection than a federal patent since New

York State courts would affirm and defend the monopoly.(10)

In 1788, Thornton helped Fitch defend his state patent before a committee of the Pennsylvania legislature, and lobbied at least one congressman for a federal patent. In 1791, while in Tortola, he urged Fitch to patent a copper boiler for the steamboat, and in 1794 offered to help Fitch get a patent for a navigational aid. Thornton never applied for a patent. He relished his role in the steamboat company as he became its principal investor and most enthusiastic director. He also prided himself on a superior understanding of the scientific principles and in return Fitch seemed to enjoy when Thornton's scientific understanding of condenser, cylinder and air pump didn't make the steam engine any better. Fitch kept a diary of their travails; Thornton didn't and then went to Tortola for two years while Fitch tried to build another boat, the Perseverance, to replace his smaller and briefly successful boat.(11)

Thornton did not present himself to Fulton as merely a company director whose ideas helped John Fitch improved his steamboat. He later wrote: "We worked incessantly at the boat to bring it to perfection, and some account of our labors may be seen in the travels of Brissot de Warville, in this country; and under the disadvantages of never having seen a steam engine on the principles contemplated, of not having a single engineer in our company or pay, we made engineers of common blacksmiths;...." Thornton claimed priority of invention not only because he had ideas about steamboats, he also experienced the building process by giving instructions to craftsmen.(12)

He would also claim that he had no idea that Fulton was about to apply for a patent, and that his own January 1809 patent for steamboat improvements pre-dated Fulton's application by a few days was pure accident. Fulton laughed at that. It is clear that both the opportunity to profit off Fulton's enterprise and his own financial predicaments were weighing on Thornton.

In December 1808, Thornton wrote two letters to his boss who was by then president-elect. The first was a draft of a pro forma patent application asking for exclusive rights to profit from his steamboat improvements, to wit: "your petitioner has invented certain Improvements in Steam boats, including modes of propelling the same by Paddles, or a wheel or wheels at the Stern and improvement in boilers for Steam Engines for the Same, & for every other purpose where large & very hot fires are required; and also for the use of a certain kind of coal which gives out much heat in proportion to its quantity which renders it peculiarly useful for navigation with Steam." At that time, Thornton was trying to bully a patentee, who used anthracite to make printer's ink, into letting him be his agent. He had evidently boned up on the virtues of that species of coal. The second letter sent eight days later outlined the dimensions of his personal financial problems.(13)

Both letters are in Madison papers, but he didn't reply to either. He may have never seen that version of Thornton's patent application. However, their juxtaposition likely transfixed Thornton. While Fulton and his associates were about to make immense profits, he had been cheated of his legacy and faced impoverishment. In May 1809, Thornton offered to help Fulton.(14) He evidently did not get a response because he began his campaign to inform all interested parties that Fulton's patent was useless and described nothing new. However, he didn't sue Fulton and defend his own patent.

He began alerting state legislatures including New York's that Fulton's patent did not describe a novel invention. Being intimidated into giving his company monopoly rights for steamboat service was not in the national interest. Both the Virginia and Ohio legislatures refused to give Fulton a monopoly.(15)

When Fulton decided to confront Thornton's claims with a counter-offer, he did not bicker about patents. He first admitted that if what Thornton had told him was true, it behooved him, for the good of the nation, to hear about Thornton's "steamboat inventions and experience." He also offered Thornton $150,000, if he made or demonstrated principles that proved that a steamboat could make 6 mph in still water with a 150 ton burden. Thornton claimed that his boat had reached 8 mph. Thornton later claimed that he accepted the challenge and asked for details about its terms. But that is as unlikely as his claim that he challenged Latrobe to a duel. Thornton wanted acceptance and recognition for what he had done. He did not have prove himself. Once again, he knew it all. For example, not only had he proof that he had suggested to Fitch that he use a paddle wheel to power the boat, he knew of a paddle wheel described in a book written a hundred years ago. If Fulton bought Thornton's knowledge and experience, he would keep that early paddle design their secret.(16)

In 1811, Fulton got a second patent. His final and relatively amicable attempt at an agreement required Thornton to attest before a judge to various improvements Fulton made to steamboats presumably in return for a monetary consideration. Thornton's long illness during the summer of 1811 stopped Thornton from cooperating.(17)

In 1812, the Fulton company decided to enforce its patent and license steamboats on all other rivers. It advertised throughout the nation that it would defend its patents and would take half the profits after 10% was deducted for capital expenses. On February 12, Fulton wrote to Secretary of State Monroe and excoriated Thornton's shenanigans. He never took out a patent for his improvements to Fitch's boat until just before Fulton applied for a patent. Then Thornton offered a partnership with Fulton and Livingston for equal thirds. He then offered to co-operate for 1/8th of the profits. Finally, he threatened to destroy Fulton's patent through litigation. Fulton argued that it was absurd if not illegal to allow the director of the Patent Office to do that.(18) In 1827, in reply to a similar complaint, Thornton crowed after a decade of demeaning a patent: "The disappointed applicants then turned to Secretary of State Madison and to President Jefferson to turn me out of office; but these good patriots smiled at turning out an officer for fearlessly doing his duty for his country."(19)

Also, government clerks were rarely fired. Thanks to a gentlemanly tradition of the young republic, they had lifetime tenure unless they grossly mishandled the government's money or became a notorious drunkard. Once in office, poverty did not disqualify an employee. Indeed, resigning because of financial difficulties was dishonorable. The price of living in Washington's official circles was high and must be born.

According to his wife's notebook, on the evening of April 11, 1812, Thornton "had a long talk" with the president "respecting Fulton & c." It is unlikely that he was being called to respond to Fulton's complaints. On the 16th, he had another long talk with the president and on the same day sent a memorial to congress which asked for a higher salary, a doorkeeper and franking privileges for his mail. It would appear that what began as a quest for executive support for his rights against Fulton, ended with executive support for his usual annual fight for a higher salary. Thornton was bitter and wrote to a friend: "If I had never accepted any Employment under the last & present administration I should I really believe have been many thousand Dollars better in Situation than at present. Man is a very selfish Animal." He added a couplet: "I really think a Friend at Court/Is but a kind of Friend in sport."(20)

In March 1813, the steamboat controversy again crossed Madison's desk. Fulton cursed "a conspiracy to track down my patent rights." He railed against "So scandalous an attack on mental property, and the sacred right of an inventor, from a Governor a general A man who Should from the high Station he fills be the guardian, the patron of science; and protector of the laws, will Sir I am certain never find Sanction or aid from your honest and upright heart." Thornton in the meanwhile had not jumped in rank from major to general. Fulton was attacking General Aaron Ogden, a New Jersey politician, who wanted to start a steamboat service from his state to New York City. He was more of a threat than Thornton because "he has built a steam-boat on my plan—copied me...."(21)

Thornton aided and abetted Ogden's conspiracy, but a competing steamboat service on the Hudson didn't mean anything to Thornton. He had not been involved in building a boat since 1789. Fitch and Fulton remain the rivals for the honor of having invented the steamboat. Fitch got his patent in 1791, and the boat he then built was never finished. Fulton got his patent in 1809, two years after a successful voyage. After he got his second patent, his company continued to make boats. The steamboat built for the Potomac arrived in 1815.(22)

Ogden's suit against Fulton morphed into a suit against one of his partners. Ogden caved into the monopoly, but Gibbons refused to and refused to take his boat out of Ogden's ferry service between New Jersey and New York. Gibbons v. Ogden worked its way up to the Supreme Court in 1824 and the court embraced the argument of Daniel Webster that the Constitution's commerce clause was overriding. Patents had no bearing on the court's decision. Ogden's pro-monopoly attorney adroitly put the Patent Office in its place: "If the States have not that regulating and controlling power, as Congress assuredly has it not. What is the consequence? A patent can be got for any thing, and with no previous competent authority to decide upon its utility or fitness. If it once issues from the patent office, as full of evils as Pandora's box, if they be as new as those issued from thence, it is above the restraint and control of the state legislatures, and the legislature of the United States, of every human authority!"(23)

No one knew that weakness in the patent law better than Thornton. In 1814, Thornton realized that his claim to fame could not depend on his own patents. He had to craft a narrative giving himself credit for Fitch's success and prove that Fulton gained access to all he had shared with Fitch. His pamphlet had a curious title: "Short Account of the Origin of Steamboats Written in 1810 and Now Committed to the Press, 1814." That he waited until 1814 to make his case public may reflect his desire to keep open private negotiations with Fulton. However, it wasn't until 1814 that two crucial witnesses who could challenge his claim died. He had found a prominent inventor who attested that Fitch's principal assistant told him that the paddle wheel was Thornton's idea. That assistant died in early 1814. A fellow bureaucrat attested that while in Paris, he was told by an American consul who was Fitch's agent that in 1793 he had given Fulton a complete set of Fitch's drawings and specifications. That agent died in 1813.(24)

Thornton had his account published in the Washington City Gazette on July 18. The editor applauded him for it, congratulated Fitch for inventing the steamboat and excoriated Fulton for claiming a monopoly based on a boat that had nothing new. Of course, New York State awarded a monopoly based on his boat's performance not on any claims in his patent. As for the judgment of history, Fitch's boat was essentially a ferry service on the Delaware River between Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware. It was faster than Fulton's boat, but the latter did complete overnight voyages between New York City and Albany. As for Thornton's role, he gave money and advice of varying efficacy to Fitch, and did all he could to stop Fulton.

The death of Fulton in February 1815 relieved Thornton from further insinuations about their relationship. Fulton's close friend Joel Barlow who tried to make Thornton amenable to Fulton's improvements died shortly before Fulton. Thornton continued to be a source of information damning Fulton's pretensions, and litigants and anti-monopoly pamphlet writers had no need to attack Thornton's patents.(25) Fulton had told Thornton that if his patents were deemed useless, Thornton's would fail as well. Thornton assigned his patent rights to his old friend Ferdinando Fairfax who blustered about law suits. When congress extended the Fulton patents to protect that company's investments, Fairfax lobbied for the extension of Thornton's patents, but there were no investments to protect, only Thornton's legacy.(26)

In that regard, by 1819, Thornton had simplified and elevated his role. Fitch was "a poor ignorant and illiterate man." The boat was too slow. Thornton "engaged to make it go at the rate of eight miles an hour within 18 months.... In one year I succeeded." Another steamboat was "rigged schooner fashion to go to New Orleans." Then "I went to visit my mother in the West Indies where I was born, and staid away two years; but on my return I found that they had never been able to make her move, & to pay the debts incurred by this want of success they had sold the boat and the whole apparatus." Then at "the time the patent expired Mr. Fulton came to America from Europe and began a steam boat with the late Chancellor Livingston. But Mr. Fulton had seen my papers describing the steam boat in the hands of one of Fitch's partners in France to whom I had sent them to take out a patent there.... [Fulton] of course succeeded but without having invented a single improvement. Success however give him not only all the profits but the eclat of the Invention, with those who are not acquainted with the circumstances."(27)

Thornton wrote as if Fulton were still alive. Fortunately for Thornton's tale, all the other principles were dead. Actually, Fitch was a prolific writer and his papers remain in several libraries from New York City to Washington. Fairfax died in September 1820.

On July 4, 1820, his friend Tench Ringgold, the Marshal of the District of Columbia, announced the sale at auction of all of Thornton's property on August 4th including his house on F Street which he had bought in 1804 for $4,452 at the court ordered auction of Blodget's property. Ringgold's auction was to satisfy three writs tied to his failure to pay for land bought by Thornton for the North Carolina Gold Company.(28)

Thornton managed to void the sale likely thanks to a friend's personal loan. That loan did not solve his financial problems. In the spring of 1822, Thornton asked his boss and neighbor, Secretary of State Adams, for an advance on his pay. He told Adams that the tax-collector had just "seized all his furniture, for the payment of 220 dollars of taxes for the last three years..."(29)

Thornton survived. He perfected the art of finding other gentlemen to secure future payment of his loans and thus extend the time of payment. Thornton never shied from asking his bosses for loans. Madison accommodated him with $150. Adams said no.(30) Banks put up with him because periodically he got unimpeachable credit in Pounds Sterling thanks to the Tortola plantation. Gentlemen friends put up with it because he entertained liberally. From his farm he got produce and meat; rum and brandies came from Tortola; his wife, with help both white and black, mastered the situation.(31)

Thornton's reaction to finally seeing how small his schemes and dreams turned out to be was to find bigger dreams. He sent his testimonial about the steamboat to the American consul in St. Salvador, Brazil. While he did get the right to license steamboats on the Magdalena River in Columbia,(32) he was more interested in liberating the rest of South America. From 1801 to 1809 and 1820 to 1825, Thornton's neighbor on F Street was the secretary of state, and both became president. That alone might inspire interest in foreign affairs. However, in an 1821 letter, he explained to Jefferson that he had been interested in the liberation of South America for almost forty years. He was "anxious" for revolution "while I was a Student at the University of Edinburgh, also in London & Paris."(33) At the time medical student Thornton supposedly got his revolutionary fervor, Francisco de Miranda, the Venezuelan revolutionary, was still an officer in the Spanish army fighting Britain in the New World when Spain lent support to the revolting British colonies.

In June 1804, Baron von Humboldt, the famous Prussian naturalist visited Washington and shared political and scientific information about his five year tour of South America and Mexico. He met and dined with Thornton and looked at his drawings of Tortola plants and Thornton later sent him a copy of a cinchona.(34) In 1805, Miranda came to Washington looking for help as he raised an army to liberate Venezuela. That is likely when Thornton got his revolutionary fervor.

In 1807, during the treason trial of Aaron Burr in Richmond, General William Eaton, just back from "the shores of Tripoli," testified that he was asked by "a gentleman near the government... if I would take a command under the celebrated General Miranda." Just as he rejected Burr's plan to overthrow the American government, Eaton was not attracted to "the project of darkness" aimed at liberating Venezuela from the Spanish crown. He got the conspirator to admit that he wasn't authorized by the US government. A defense attorney asked: "Who was that man? Answer: Dr. William Thornton."(35)

Thornton's possible violation of the Neutrality laws did not lead to an investigation. Politically, the revelation made little difference. During the 1806 trial of Americans who helped arm or fight with Miranda, including John Quincy Adams' brother-in-law William Smith, the defense tried in vain to link Jefferson and Madison to Miranda. Thornton was decidedly small fry in that regard.(36)

Then from F Street, he supported the revolutionaries as best he could even while tied to the "trivial office" to which Jefferson had appointed him:

I have been always considered, by the South Americans, an active Friend; & they have made me several offers of high appointment in their Service; but though I was engaged only in the trivial office I still hold, which does not give support to my Family, I have invariably refused every temptation to enter into the patriot Service; wherein I was offered the immediate rank of Colonel of horse; & a high office in their Civil Service; with land enough whereon to settle a Colony. I refused every thing, but rendered them, as a friend, every Service in my power, & all the great revolutionary Characters of South America have considered my House, as a place of friendly Consultation.—

Thornton wanted Jefferson to persuade President Monroe to send him to Columbia. In the same letter, Thornton had asked about the design he sent for the university. In his reply, Jefferson didn't mention it. As for a diplomatic mission, he assured Thornton that his talents were well known and, "with every disposition in your favor," wished him well.(37)Thornton had not been shy about projecting his ideas about the future of the Western Hemisphere. In 1815, he had published his constitution for the union of North and South American republics. He also projected another monumental building. Up in Quincy, Massachusetts, it gave John Adams a good laugh. A friend wrote to the former president about Thornton's "....One Grand Republican Government, to be placed under the surveillance, and legislation, of a Congress of Deputies from all the Cities, and all the States, not only of South, but also of North America, who should hold a permanent sitting on the top of Mount Chimborazo, twenty thousand feet above the level of the Sea;..." Thornton knew the mountain well because Humboldt had climbed it doing scientific research.(38)

Such outlandish ideas did not interfere with American foreign policy that for the moment had the limited goal of acquiring Florida. Then Thornton complicated that. In a February 18, 1818, letter to Madison, President Monroe raged that Thornton's Miranda episode had been eclipsed by a dumbfounding report that former Attorney General Rush had supported a plan hatched by Thornton for the government to buy East Florida for $1.5 million from an adventurer named McGregor. Monroe fumed: "Of the absurdity of such a statement, and the impossibility, that Mr Rush, should have warranted it, by any thing on his part, both his character & that of Dr Thornton seem to afford full proof." In his reply, Madison did not impugn Thornton's character, but marveled that anyone could come up with such a stupid idea.(39)

Thornton was conducting diplomacy on his own. The president was not amused. Thornton asked his boss, the secretary of state, to arrange a meeting with Monroe so he could explain his association with "South American Patriots." John Quincy Adams told Thornton that "the President said he would not see him, nor have any conversation with him upon any thing, unless it were Patents, and very little upon them."(40) The chances of Thornton forming a relationship with Monroe in regard to the restoration of the Capitol were nil.

However, Adams, who would succeed Monroe, would talk with Thornton about South America and everything else until the frustrated revolutionary's dying days. They also had ample opportunity to discuss the Capitol. On October 31, 1819, just before congress returned to the restored Capitol, Col. Lane gave Adams a tour. In his diary, he wrote that the Senate chamber was too small; the House chamber "magnificent, but not convenient, nor in good taste." Lane told him the building stone of the Capitol was "too soft, and before many years will crumble into sand." That night Thornton dropped in to visit Adams at his home just below Capitol Hill. In his diary, he noted that Thornton "was amusing." He evidently didn't talk with him about the Capitol. Adams soon bought the house next door to Thornton's on F Street and moved into in October 1820. He was Thornton's neighbor until he moved into the President's house in March 1825.(41)

Only once did Adams allude to any discussion of the Capitol with Thornton, but he looked to Thornton for artistic advice not architectural. When none of the entries in a design contest for the tympanum above the east portico entrance to the Capitol would do, President Adams mentioned three men including Thornton who might come up with a winner. On July 17, 1825, at a time when Adams could not devote much time to his diary, he noted: "Visit from Dr. Thornton - Design for the Tympanum" and below that "Portrait of Bolivar."

Whatever Thornton might have said about the design, Adams came up with an arrangement that he called his own. Likely most of the conversation with Thornton was about the Liberator of South America.(42) Adams himself is credited with the design.

Thornton began pressing Adams for appointment to a diplomatic post before Adams moved next door. Adams explained to him "that as he had always been a very ardent South-American Patriot, perhaps the President might think a person more cool, would suit better for the impartial observation necessary to such an agency— [Thornton] thought that very strange; for in his opinion, it was precisely that which made him peculiarly fit for the Agency." A few months earlier, Adams had already concluded "The Doctor is the most indefatigable, and irrepulsable candidate that I ever knew."(43)

Being Thornton's neighbor increased Adams' affection for the eccentric. Sometimes Thornton gave Adams unalloyed pleasure. One spring evening in 1821, "we spent the Evening at Dr Thornton’s where we were entertained with Music— Mrs Thornton performed on the Piano, and sung Handels’ Anthem of 'Comfort ye my People'—much to my satisfaction." Adams played chess with Thornton, once Adams went to the Quaker meeting with Thornton, and Thornton frequently joined Adams at his usual Sunday services. Adams admired Thornton's drawings and objets d'art and laughed at his jokes, although one evening he dismissed the latter as "buffoonery." Sometimes it went down better and Adams jotted: "Thornton gave us after dinner a perfect surfeit of buffoonery."(44)

But the importuning never stopped. In an 1822 diary entry, Adams put it this way: "The Doctor is a native of the Island of Tortola; a Man of learning, ingenuity, wit and humour; well meaning, good-natured, and mainly honest, but without judgment or discretion. I told him there would probably not be an early appointment of a Minister at Rio Janeiro."(45)

After he moved into the White House, Adams kept track of his old neighbor whose health was poor during the last three years of his life:

...I called to see Dr Thornton who is ill in bed. He has been for some months much out of health, but had apparently recovered, and was last Sunday Evening with Mrs Thornton at my house— He was very suddenly seized that same Night, and has not since left his bed— He is exceedingly reduced both by his disease and his remedies— He can scarcely speak, but retains his facetious humour, and his South-American ardour— He was very fearful that the British would cut a canal for Line of Battle and India Ships, and obtain an exclusive right of navigating for forty years.

In those days government officials were not replaced or expected to resign because of bad health. Adams wasn't checking on Thornton for that reason. He knew that Thornton's clerk, William Elliot "has done most of the business for some years and was eminently qualified, by his knowledge of mechanics and of all the mathematical Sciences."(46)

Much as he wished to be sent on a far flung mission, Thornton's staying power served him well. If he had become a diplomat, his rhetorical campaign for revolution would have been muted thus losing him the plaudits of newspaper readers who preferred his stirring analyses to staid state papers. He had also published his opinions on protective tariffs and other financial topics. He urged the government to issue $100 million in paper currency secured by an increase in the national debt secured in turn by land and building infrastructure. Another $100 million could buy Southern slaves to be put to work on roads and canals long enough to redeem the money spent to buy them and to then be freed. Fears that paper money could be counterfeited were unfounded "because I have invented a public as well as private test" to reveal forgeries which "I am ready to communicate at anytime to the government."(47)

His plan for emancipation echoed his 1804 pamphlet but in it he had urged the settling of freed slaves in the furthest reaches of the Louisiana Purchase. In 1819, he waffled on that. In 1816, he had cheered the formation of the American Society for Colonizing the Free People of Color of the United States. Its goal was a black republic in Africa. Thornton alerted the society that in 1787 blacks in Rhode Island responded to his call: "They were delighted with the prospect, and in a few weeks informed me that two thousand were ready to accompany me." In 1820, 86 free blacks left the US for what was to become Liberia.

In his 1819 essay, Thornton did not pinpoint where freed slaves would go. That equivocation even entered his will. He didn't mention the Tortola slaves but left his wife eleven American slaves valued at $2,665, not that he wanted them sold. Provided that the slaves were educated, he wanted them to have a plot of land or a ticket to Africa. But his will cautioned that they could be sold if they "behaved so improperly as to require it." There is no evidence that he ever freed a slave.(48)

The Intelligencer reported that on February 29, 1828, John Tayloe, aged 56 years, died and that his remains would be removed form "his house in this city" for internment at Mount Airy. During the last years of his life, he was plagued by stomach problems. Thornton died on March 28 at his F Street house.(49) He left no reaction to Tayloe's death. Dying so closely in time prevented a survivor, preferably Tayloe, from reflecting on Thornton's graciously designing the Octagon. That would add an endearing aspect to the doctor's storied life: he took the secret of his design to the grave. But he never seemed to have been one to keep secrets that amplified his attainments.

In the wake of his wife's death in 1865, a secret was revealed. It could been about the Octagon because in his wife's obituary Thornton's design of the Capitol was remembered. The completion of the New Capitol during the Civil War prompted remembrances of the Old Capitol which was generally called the "original Capitol." Thornton had long been credited with the "original design of the Capitol." In Mrs. Thornton's obituary he was credited as the designer of the "original Capitol" which consigned Latrobe and Bulfinch to the dust bin of history.

The secret revealed pertained to Mrs. Thornton: "Mrs. Maria Thornton, widow of the celebrated William F. Thornton, first United States Commissioner of Patents, died on Wednesday night in this city.... Mrs. Thornton was the daughter of the unfortunate Dr. Dodd, of London, who was executed for forgery in 1777." The obituary concluded by citing a source for her pedigree: "It is not believed that she was aware that she was the daughter of Dr. Dodd, although her husband was, and mentioned it to his friend, the late Col. Bomford." Her "most intimate friends" responded that they "have never given credit to that suggestion." However, they acknowledged that Mrs. Brodeau "never, in any manner, alluded to her life before she came to America." Benjamin Ogle Tayloe, the son who didn't credit Thornton for designing the Octagon, did write about the Dodd connection in the memoir he wrote a few years before Mrs. Thornton's death: "Dr. Thornton fell in love with her daughter, and married her, after being informed by her mother of her real name and parentage."(50)

There is little mystery about Dr. Dodd's life. No less than Dr. Samuel Johnson led a petition campaign in a vain effort to save the reverend who wrote "Thoughts in Prison" while awaiting execution. His wife, a former house maid, visited him. None of the lore about him mentions a daughter or love child. On a regular basis, he preached to fallen women aided by the Magdalen Society of London. Otherwise, he was a flamboyant show off and bankrupt which is why he forged a check for 4,200 Pounds.14 In 1777, just before Dodd forged the check that led to his execution, he wrote a letter to his friend Benjamin Franklin in Paris and asked him to forward a letter to "a worthy young woman, who in an unfortunate hour, went to America and to whose fortune and situation there, I am a stranger." The editor of Franklin's papers wrote in a footnote: "We are convinced in our bones (in other words without proof) that this was Ann or Anna Brodeau, who emigrated to Philadelphia with a small baby in 1775 and started a school that was recommended by BF and Robert Morris:... Dodd, according to a long-lasting rumor, was the father of the baby. She grew up to marry William Thornton, and at her death a newspaper described her, on her husband’s authority, as the clergyman’s daughter; her friends denied the statement but gave no evidence."(51)

One has to wonder why Thornton told the story to Col. George Bomford who he probably met around 1812 and who became a friend in the mold of Col. Rivardi. Rivardi built forts. In 1811, Bomford invented the largest smooth bore, muzzle loading cannon in the world. Of course, Thornton could have told others and only Bomford broke the secret. Men like Washington, Jefferson, Lettsom knew of Dodd. It wasn't a question of waiting until Mrs. Brodeau died because she outlived Thornton. He was 18 years old when Dodd was hanged. By that time Thornton could brag that he had forged a five Pound note. As Allen Clark told the story in "Dr. and Mrs. Thornton": "When a lad at school he handed his uncle two 5 Pound notes and asked him to select the one better engraved. The uncle selected the counterfeit just made by young Thornton." Clark did not mention the story about Dr. Dodd and Mrs. Thornton. By 1819, Thornton had "invented" a test to detect forgeries which also suggests that Thornton well remembered Dr. Dodd.(52)

That no one could identify Mrs. Thornton's father does not prove it was Dr. Dodd. But no one would have been more pleased than her husband to tell people that it was Dr. Dodd. It suited his modus vivendi to lie about it. Surely, in his own mind, it was a white lie. After all, he had been looking for a wife with a sizable dowry. The story also added a Romantic hue to a woman who had been such a dutiful wife. Bomford was a likely man to tell. His birth records did not list a father and his second wife also "sheltered a personal history." Bomford proved a stalwart in helping widow Thornton pay off her husband's debts. The Bomfords' daughter Ruth and her husband named their second child Anna Maria Thornton Paine.(53)

Devoted thought she was to the doctor, in a memoir after his death, Anna Maria Brodeau Thornton summed up his failures. She regretted his embracing "a greater variety of sciences" because it prevented him from attaining what he truly wanted. She credited him for genius in many fields - "philosophy, politics, Finance, astronomy, medicine, Botany, Poetry, painting, religion, agriculture, in short all subjects by turns occupied his active and indefatigable mind." She concluded that "had his genius been confined to fewer subjects, had he concentrated his study in some particular science, he would have attained Celebrity."(54)

She didn't list architecture which didn't prevent historians from making him one of Washington's, if not America's, greatest architects. Obviously, he was influential, but in a perverse way. If an architect is one who facilitates building, then Thornton was not the First Architect of the Capitol. However, for presidents, his "ideas" about the Capitol shielded them from congressional interference. For congressmen, his envy and anger at architects enabled their unceasing complaints about and interference with whoever tried to get the Capitol built. As for John Tayloe, Thornton did not design the Octagon. He was not the type of genius who would cheapen a design for a wealthy man. Instead, he designed a house for an angled lot that would rival Tayloe's. He also set out to breed better horses than Tayloe. He never did and never built his house. Ironically, at the end, Thornton wished to be far away. But he was never sent to South America or anywhere else. In a perverse way, the city needed to keep him. Thornton's ego otherwise proved a valuable check on bothersome unelected outsiders with too many ideas. Once sent to the Patent Office, not a few inventors learned from Thornton that there was nothing new under the sun.

1. Daily National Intelligencer 4 April 1828.

2.Preston, Journal of the Early Republic, "Administration of Patent Office...." Vol. 5, No. 3 (Autumn, 1985), pp. 331-353 p. 346.

3. AMT notebook, volume 4, image 4-24; Henry Clay Papers, Clay to Mrs. Thornton, 2 November 1828; American Farmer no. 6 vol. 10 p. 28.

4. Bickley v. Blodget cited Boyd v. Camp in Washington Law Reporter vol. 37 pp. 14ff; Blodget's financial problems are a described in a monograph on his Philadelphia mansion; WT to Madison 17 December 1808 .

5. AMT notebook, volume 3, image 47; American State Papers Misc. vol 2 p. 193.

6. National Intelligencer, 25 March 1819, 1 April 1819.

7. Preston, p. 346.

7A. WT to Jefferson 20 January 1812; 13 July 1812; 27 June 1814; 3 April 1815; 22 March 1816

8. JQA diary, 27 December 1804; Preston, p. 344; Jefferson to Allison, 20 October 1813.

9. Jefferson to Fulton, 16 August 1807, ; Century Magazine, vol. 78, 1909 p. 834; Fulton to Jefferson 9 January and 28 July 1807 ; AMT notebook, vol. 3 image 24 -

10. New York State Library "Steamboats on the Hudson"

11. Harris, p. 148; WT to John Vining 16 June 1790, Harris p 116; WT to Fitch 21 June 1791, 21 March 1794, Harris, pp. 141-7, 277;

13. WT to Madison, 9 & 17 December 1808 ;

14. AMT notenbook vol. 3, Image 66, February 12; May 13; AMT vol 3 image 6,7

15. for WT letter to Virginia legislature see appendix #2 Thornton, Short Account of the Origin of Steamboats

16. Clark pp. 186-7

17. (Mostly) IP History blog; Century Magazine vol. 70, 1909 pp. 832-3

18. Dobyns, Kenneth, History of the Patent Office, chapter 9,

19. The Daily National Journal 4 May 1827 p. 2.

20. AMT vol. 3 image 181; Annals of Congress, 12th 1st session p. 1324; Thornton to Steele, 18 April 1812, Papers of John Steele NC Digital Collection page 219.

21. Fulton to Madison, 18 March 1813.

22. AMT notebook June 1815.

23. Reports of Decision of the Sup. Court of the US, February term, 1824, pp. 154-5.

24. Thornton, Short Account of the Origin of Steamboats Written in 1810 and Now Committed to the Press, 1814 ; Henry Voight died February 7, 1814, and Aaron Vail died November 21, 1813. Thornton's account appeared in the July 18, 1814, Washington City Gazette.

25. see Duer, William Alexander, Reply to Mr. Colden's Vindication of the Steamboat Monopoly, 1819. pp. 87

26. Westcott, Life of Fitch, p. 404: Annals of Congress, 14th congress first session, House, March 15, 1816, p. 204.

27. WT to Henry Hill 20 April 1818, in Clark, "Dr. and Mrs. Thornton" pp. 187-8; See WT to John Vining, 16 June 1790, Papers of William Thornton, for WT's celebration of Fitch's genius.

28. on purchase of house Harris, p. 560; National Intelligencer 4 July 1820.

29. J.Q. Adams diary, April 30, 1822

30. October 3, 1822 "Dr Thornton called at the Office, with a proposal to borrow money, which I declined—; Account with William Thornton, Madison Papers, 5 December 1809;

31. E.g., WT to Law 9 March 1801, Harris p. 553.

32. AMT notebook vol. 4 (1828) p. 11

33. WT to Jefferson, 9 January 1821,

34. Friis, Herman R., "Baron Alexander von Humboldt's Visit to Washington, D. C., June 1 through June 13, 1804"

Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C., Vol. 60/62, p. 27 (book version)

35. American State Papers Misc. vol. 1, p 539.

36. Adams, Henry, History of the United States During Second Administration of Thomas Jefferson, pp. 195ff

37. WT to Jefferson, 9 January 1821; Jefferson to WT, 29 January 1821

38. James Lloyd to John Adams, 7 April 1815; reply 22 April ,

39. Monroe to Madison, 13 February 1818; reply 18 February 1818

40. JQA diary February 14, 1818; see also the diary entry for February 13

41. JQA diary 31 October 1819.

42. JQA diary, July 17, 1825.

43. JQA diary Feb 17 1820 ; Feb 2, 1821.

44. April 8, 1821; March 25, 1821 ; January 10, 1820; November 30, 1819.

46. May 22, 1825; March 29, 1828

47. Daily National Intelligencer 22 December 1819.

48. Sherrwood, "Formation of Amer. Col. Soc." Journal of Negro History 1917; Hunt, Galliard, "William Thornton and Negro Colonization," Amer. Antiquarian Soc. 1921, pp. 57ff; Jenkins, Tortola, p. 61: Berlin, Jean V. "A Mistress and a Slave: Anna Maria Thornton and John Arthur Bowen" Proceeding South Carolina Historical Associationy, 1990 (pdf) p. 70.

49. Daily National Intelligencer 1 & 29 March 1828.

50. Daily National Intelligencer, 18 & 22 August 1865; Tayloe, B.O., In Memoriam.

51. "Thoughts in Prison...." Wikimedia commons; Dodd to Franklin, 29 January 1777;

52. Clark, "Dr. and Mrs. Thornton," p. 148

53. Peterson, Nancy Simons, "Guarded Pasts: The Lives and Offsprings of Colonel George and Clara (Baldwin) Bomford." pp. 283, 298.

54. Clark, ''Dr. and Mrs. Thornton", p. 199

Comments

Post a Comment