Chapter Fourteen: Death of Washington and Thornton Designs a Mansion, for Himself

Table of Contents page 215 (continued)

|

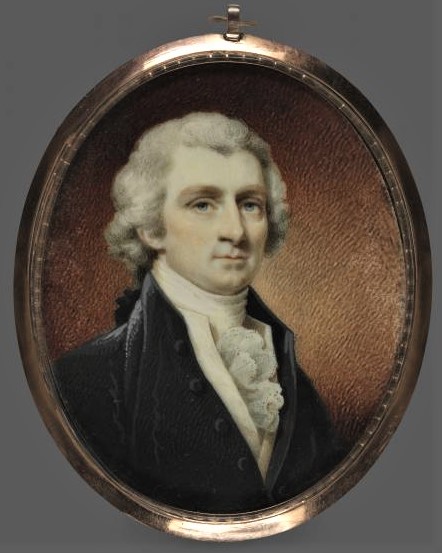

| 141. A miniature of Thornton by Robert Field, ca. 1800 |

On May 16, 1799, George Washington rode up to see an open purse race in Alexandria. William Thornton and Thomas Law were there, too. At the end of the race, Thornton and Law went to Mount Vernon with Washington and stayed three nights. The purse was only for 55 Virginia Pounds, evidently not money enough to attract Tayloe whose best horses raced page 216 elsewhere that weekend.(1)

Work had just begun on Tayloe's house. Work on Washington's two Capitol Hill houses as well as on Law's largest house started two weeks or so earlier. There is no evidence that the conversations at Mount Vernon turned to houses. Looking for social occasions when Thornton might have shined in that regard is important because there is nothing written that suggests, let alone proves, that he had anything to do with designing those houses. If he had, how could he not have talked about it?

Judging from a letter George Turner wrote to Thornton in June, Thornton and Law had likely something else in mind when they went to Mount Vernon. Turner had asked them to get the General to endorse Turner's "scheme of schemes." The editor of Thornton's paper think the scheme of schemes was a land speculation in Ohio. Nothing came of the scheme. Within a year, the American Philosophical Society investigated and expelled Turner for embezzling funds from one of the Society's committees. That limited his ability to peddle schemes to the country's elite.(2)

|

| 142. Latrobe drawing of Mount Vernon in 1797 |

Another topic of conversation at Mount Vernon may have been Thornton's scheme to make parks or put pubic amenities on oddly shaped or truncated lots made by large intersections. He had first broached the idea to Washington in early 1797 when he was still president. In early 1799, George Walker, a principle proprietor of lots well east of the Capitol, asked the board to let him market those oddly shaped parcels so that buyers of nearby building lots would not find access to nearby avenues blocked by the public amenities Thornton contemplated.

Scott and White were disposed to grant Walker that favor. He had not been able to sell any lots. His wife had died during child birth, the child also dying, making Walker's faraway mansion even lonelier. Thornton objected, arguing that giving such an allowance to one proprietor would inspire all proprietors to ask for the same privilege.

|

| 143. Walker's lots showing houses built by 1802 |

There is other evidence that in 1799, Thornton gloried in his role as the protector of the public interest and planner of public grounds. In May, Thomas Boyleston Adams, the First Family's third son, toured the city. In a June 9, 1799, letter to his mother, that was mostly favorable about the city's site and prospects, Thomas painted a dismissive portrait of Commissioner Thornton: "a democratic, philanthropic, universal benevolence kind of a man—a mere child in politics, and having for exclusive merit a pretty taste in drawing—He makes all the plans of all the public buildings, consisting of two, and a third going up."

There was no mention of the notable private house then under construction: Washington's, Law's and Tayloe's. Young Adams did mention Scott and his house: "Scott was a Lawyer of some eminence and he has built a fine house upon a hill since being in the Commission— Presumption, is that he has used the public materials in building his own house upon the hill." (4)

|

| 144. Scott's Rock Hill |

One letter written at the time gave an idea of the table talk at Mount Vernon when Thornton was there. Washington employed a secretary and in 1799, Tobias Lear, a failed Federal city merchant, had his old job back. Back in 1793 when Thornton heard that Greenleaf had backed Lear for a business trip to London, Thornton had applied in vain to be Washington's secretary. On September 12, 1799, Lear wrote to Thornton thanking him for some recent medical advice about treatment of a lame leg. He also revealed what had been on Thornton's mind as they all sat page 218 around the table:

I am very happy to learn that the prospects in the city are brightening fast. You will become every day more and more important, and I have not a doubt but the improvements will be rapid beyond example. I hope the grand and magnificent will be combined with the useful in all the new public undertakings. We are not working for our selves or our children; but for ages to come, and the works should be admired as well as used. Your wharves and the introduction of running water are among the first objects. Let no little mindedness or contracted views of private interest prevent their being accomplished upon the most extensive and beautiful plan that the nature of things will admit of - and - But hold, I am talking to one who has considered and understands these subjects much better than myself, and who, I trust, will exert himself to have everything done in the best manner.(5)

Thornton did defend the private interests of his great patron. Once word got out that the General was building, John Francis, who boarded congressmen in Philadelphia, had immediately expressed an interest in renting Washington's houses. Washington asked Thornton what the customary rent would be. Thornton researched the issue and suggested a rent of 10% of the cost of construction which would have been $1200 for both houses.

Francis approached Commissioner Thornton to see if, as well as renting the houses, he could buy a lot and build next door. He needed more room for boarders. Since Francis also wanted to build back buildings behind Washington's houses, Thornton wrote to Washington that he “refused to name any price,” and Francis lost interest. But not to worry, if Francis hesitated to rent Washington's houses, Thornton had a better idea. He advised Washington to sell them:

....preserve them unrented, and keep them for sale, fixing a price on them together or separately; and I have no Doubt you could sell them for nine or ten thousand Dollars each, and if you were inclined to lay out the proceeds again in building other Houses this might be repeated to your Advantage, without any trouble, with perfect safety from risk, and to the great improvement of the City. I am induced to think the Houses would sell very well, because their Situation is uncommonly fine, and the Exterior of the Houses is calculated to attract notice. Many Gentlemen of Fortune will visit the City and be suddenly inclined to fix here. They will find your Houses perfectly suitable, being not only commodious but elegant.

Thornton added “You have done all in your power to render them convenient for a lodging-house without absolutely injuring the Tenements...” In reply, other than thanking him "for the information, and sentiments," the General didn't react to Thornton's suggestion that in the waning years of his illustrious life, he become a real estate developer.(6)

But then the General almost bought another Capitol Hill lot. In August, Thornton and Law seemed to work together to encourage Washington to plunge. He came to city on August 5 and 6 for a meeting of the Potomac Company Board of Directors. On the 13th, Law wrote to him that "Dr Thornton has applied to Mr Carroll who will not take less than 15d. or 15 Cents—which in truth the Lot is worth." The lot is question was the corner lot on New Jersey Avenue forming an obtuse angle on the southwest corner of Square 634. Washington's was building his houses in the middle of the block on the west side of North Capitol Street.

page 219 Here was a chance for Thornton to help the General at the beginning of a house building project, but in a letter to Law, the General emphasized that he didn't want to build. His third condition before buying was that he would only buy the lot if he was "under no obligation to improve the lot sooner than it shall conform with my own convenience; and that will depend upon circumstances not at present, under my controul." The first condition was that the lot had to be cheaper. He didn't buy the lot and didn't mention the episode in his letters to Thornton.(7)

In his letter to the General, perhaps Law set Thornton up as the man to design the house. That August, Law brought theater and English actors to the federal city. He described his joy to the General: "Last night I heard Bernard & Darley, and spent a very pleasent Eveng there were Thornton the Architect Cliffin the Poet & Painter, Bernard the Actor & Darley the Singer in short several choice spirits the forerunners of numbers such." But Thornton the Architect got no further than ascertaining that the lot Washington wanted was too expensive.

|

| 145. Bernard the Actor |

In a September 1 letter to Washington, Thornton did mention Tayloe. On August 28, the page 220 General wrote his shortest letter to Thornton, to wit: how much was the next payment to Blagden and when did it have to be paid? Thornton wrote back, answering the question and adding much more. Blagden had a "statement" about the ironmongery needed for the house. If the General found ordering it inconvenient either he or Blagden would order it.

Then he mentioned Tayloe, but not Tayloe's house: "We meant to have paid our respects to you and Mrs Washington Yesterday, but Mr Tayloe of Mount Airy spent the Day with us, and Mr Wm Hamilton of the Woodlands, near Philada is to be with us tomorrow. He is returning immediately, and laments he cannot have the happiness of paying you a Visit."

Then Thornton reported on the commissioners' business. The General had forwarded a letter from Secretary of State Pickering offering a plan for the federal city's docks that would prevent yellow fever. Thornton noted that "it is a highly interesting subject and one I have urged, for three years to the board." Then he noted continuing lot sales and added that "the Trustees, of Morris & Nicholson, are going to finish the Houses at the Point."

Then as he often did, he projected into the future of the city's public space. He noted that "the navy- yard will be fixed... where I recommended it." He had prevented it from being placed on the square designated for the Marine Hospital. He also had preserved the reservation for "a military academy, for parade-ground, for the exercise of the great guns, for magazines, etc., etc." Then he found even higher ground: "I am jealous of innovations where decisions have been made after mature deliberation, and I yet hope that the city will be preserved from that extensive injury contemplated by some never-to-be-content and covetous individuals."(8)

He didn't say how he and Mrs. Thornton spent the day with Tayloe. He probably visited Thornton to see his stable of horses. They would soon be doing business in that regard. Clifden and Driver, the two English horses Thornton imported would arrive in Norfolk in the fall.(9) Their next visitor, William Hamilton, had something in common with Tayloe. His "Woodlands" outside of Philadelphia had oval rooms. However, he was a connoisseur of garden plants and likely came to see Thornton's illustrations for the unpublished Flora Tortoliensis. The conjunction of Tayloe and Hamilton, men with oval rooms, did not inspire Thornton to develop that theme in his letter to the General.(10)

The General wrote back on the 5th, apologizing for not writing sooner. He wanted Blagden to order the iron, and didn't thank Thornton for offering to do it: "I had rather he should get it than I because he would be a better judge of it’s quality." He added that he was glad to hear that lots were selling. He didn't mention Tayloe. The General closed his letter by saying "At all times we shall be glad to see you & Mrs Thornton here."(11)

On September 20, the day before he wrote to Law, the General started a process that led to Thornton designing a house. In 1797, Washington's nephew Lawrence Lewis, then a widower, moved into Mount Vernon. His living there led to his courtship of Nelly Custis, Martha Washington's third grand daughter, and their marriage at Mount Vernon on February 22, 1799.

|

| 146. Eleanor Custis "Nelly" Lewis. 1804 Stuart |

The newly weds lived at Mount Vernon. Since he planned to give the Mount Vernon house to another nephew, on September 20, Washington revealed that portion of his will to Lewis that bequeathed 2000 acres of the Mount Vernon estate to him for the express purpose of his building a house. Washington advised him that "few better sites for a house than Grays hill, and that page 221 range, are to be found in this County, or elsewhere." Washington urged him to build quickly and if Washington changed his mind he would cover the cost of Lewis's building expenses. Washington seemed to be prodding Lewis, who had a tendency to sickness and repose, to do something.(12)

The General was somewhat repeating what he did in September 1798, deciding on a house, that led to a contract signed in November, ground breaking in April and construction during the summer. However, the General's nephew would not be hurried. In August 1800, Thornton would give Lewis a plan for his country house. It's not certain when Thornton began making his plan, but in the half dozen letters exchanged between the General and Thornton, there is no mention of it.

Throughout the back and forth about lots and houses, there is no evidence that Thornton offered to design any house. A New England gentleman bought the lot on the other side of Washington's houses. In an August 1 letter, Thornton told Law that he called on him "to recommend houses like the Generals,... but I think he has not yet determined what to do." If Thornton was indeed an architect eager to spread his genius throughout the city, one might expect more than that obvious recommendation.(13)

Thornton's friendship with Law was not about houses and development schemes. Thornton had been raised more or less as an orphan and craved to be as close to Washington and his family as he could. In that August 1 letter to Law, who was then out of town, Thornton gossiped about Lewis and Peter, who like Law had married the General's grand daughters. He relayed the travel plans of one of the General's nephews, Bushrod Washington. He also reported that the General had just recovered from an indisposition.

With the Washington Family, Thornton did not down play his medical credentials. In his September 12 letter, Lear mentioned his own fever and that Mrs. Washington was recovering from a serious illness. Thornton rushed to Mount Vernon and spent four nights.(14)

After his September visit, Thornton wrote four letters to Washington that have been lost. Washington answered them all. Save for thanking Thornton's step-father in Tortola for "the politeness he has been pleased be stow on me," the first three letters were all about the Capitol Hill houses especially painting and plastering in which Washington schooled Thornton. He took Thornton's advice in so far as wanting to sell the houses as soon as possible.(15)

It is possible that Thornton discussed Tayloe's house and in his reply the General ignored it because it was none of his business. He didn't react to Thornton's previous one sentence mentions of Tayloe in October 1798 and April and September 1799. But, in a 1795 letter to Lettsom expressing his admiration for George Washington, Thornton said that he wanted "to collect all I can concerning him.... He has a regular journal of his whole life.... I have seen in his private closet the trunks that contains these valuable memoirs."(16)

Thornton knew that by corresponding with Washington, he became a part of history. In an 1804 pamphlet, he would brag about how many letters Washington wrote to him. If Thornton had designed the first large private residences in the city, he would have noted that in a letter to page 222 Washington.

In the late fall of 1799, those two houses became the talk of the town. In November, the General came to the city to inspect his houses on Capitol Hill. Tayloe family lore describes his making frequent inspections of the progress on the Octagon. When he came in August and then again in November, he probably did look at the house. In November, he also saw the interior of Law's house. In a letter Law wrote five months later, he described the General's reaction to it:

On the ground floor there is a handsome oval room 32 by 24 and a room adjoining 20 by 28 - the oval room is so handsomely furnished that I wish to leave the eagle round glasses, carpet and couches in them as they are suited to the room - above stairs is a dressing room and a bedroom 21 by 20 - a center room with a fireplace about 17 by thirteen, an oval room 30 by 25 - and a room 20 by 11 with a fireplace - the same upstairs - say 8 bed rooms or 7 bedrooms and an oval sitting room... It is warm in the winter and cool in the summer having all the southerly wind. General Washington was so pleased with it, that he said "I would never recommend to a wife to counteract her husband's wishes but in this instance, and I advise Mrs. Law not to agree to a sale"....(17)

|

| 147. Law was so excited by the fan shape of his kitchen in the basement that he drew it |

Then Law accompanied the General back to Mount Vernon, as did Commissioner White, James Barry and Thornton. That was the prefect time for Thornton to reveal his genius as a residential architect. After they saw Law's oval rooms, he could have described the oval rooms planned for Tayloe's house. But, he had not designed those ovals. All the guests left the next morning.(18)

Ten days later, Thornton alluded to the two houses in a letter to President Adams. On November 21, 1799, Commissioners White and Thornton reported that while the buildings for congress and the Executive departments would be ready, finishing the President's house would page 223 cost $32,480.57 and raising that amount depended on collecting debts which was a problem. If the President's house wasn't ready in time, they assured the president "that a good house in a convenient situation may be provided at the seat of Government for the use of the President until that intended for his permanent residence shall be finished."

Then on December 13, 1799, Commissioner White paused in Leesburg, Virginia, during a snow storm as he made his way from the federal city to his home in Winchester. There he wrote a private letter to President Adams that amplified the assurance made in the board's letter. "It was not thought proper in a public paper to be more particular," White explained, "but the houses alluded to were, one building and in great forwardness near the Presidents Square, by Mr Tayloe of Virginia, and two new houses built by Mr. Carroll and Mr Law, near the Capital—Any one of these three is better than the President of the U. States, as such, has resided in—."(19)

|

| 148. Daniel Carroll of Duddington's house |

White visited Mount Vernon as frequently as Thornton did. Washington wrote to his old friend White about things that he didn't discuss in his letters to Thornton. The General wrote letters to both of them on December 8, 1799. Both had written to him with news that the Maryland legislature bought stock in the Potomac Company. White's letter is missing but judging from Washington's reply, he discussed worries and rumors about a shortage of housing near the Capitol. In his reply, the General discussed the news about the Potomac Company. Then he sorted through rumors and innuendos about the housing situation that sought "to the attempt of diverting the followers of the Government from engaging houses in the vicinity of the Capitol." He trusted "that matters will still go right."(20)

In his letter, Thornton reported that the attorney general ruled that the commissioners could not get a loan. Thornton also reported that the Maryland legislature approved plans to page 224 build a canal connecting the Chesapeake and Delaware bays. Thornton knew that news would cheer the General and it did. Other correspondents shared the same news but only in his reply to Thornton did the General strike a tone celebrating the march of progress:

As a citizen of the United States, it gives me pleasure, at all times, to hear that works of public utility are resolved on, and in a state of progression—wheresoever adopted, and whensoever begun. The one resolved on between the Chesapeake and Delaware is of great magnitude, and will be, I trust, the Precursor of another between the Delaware and sound, at Amboy. These, with the one now about, between the Chesapeak (for Norfolk) and Albemarle Sound, will, in a manner, open a kind of Inland Navigation (with what assuredly will be attempted in the Eastern States) from one extremety of the Union to the other.

Then Washington addressed the board's problem: "no doubt ever occured to my mind" that the commissioners could get a loan. Then, much as Thornton did in his September 1 letter, he celebrated the big picture and also vented his spleen: " by the obstructions continually thrown in its way—by friends or enemies—this City has had to pass through a firey trial—Yet, I trust will, ultimately, escape the Ordeal with eclat. Instead of a firey trial it would have been more appropriate to have said, it has passed, or is on its passage through, the Ordeal of local interests, destructive Jealousies, and inveterate prejudices; as difficult, and as dangerous I conceive, as any of the other ordeals."

The General discussed housing problems with White, not with Thornton. That serves as evidence that he didn’t design and Tayloe’s and Law’s houses. At the same time, it is evident that the General truly liked the younger man so eager to serve and so eager to share his visions of the future. What vexations Thornton had caused had long been forgotten. The General had avoided other vexations by not giving Thornton too much head in the matter of building two plain houses on Capitol Hill. The General had much to do with Thornton rise, and Thornton knew it. A week after writing that stirring letter to Thornton, the General was dead.

Thornton joined the Laws as they hurried to Mount Vernon at the news of the General's decline, but they arrived a day late. Years later Thornton wrote down a curious twist to his grieving. He fantasized that he urged the family to take advantage of a winter cold spell which preserved the corpse and let him bring the general back to life with a tracheotomy and blood transfusion. Not a few biographers and historians dutifully record that Thornton did indeed suggest that.

The premise is false. Thornton recalled that the weather was "very cold, and he [the body] remained in a frozen state for many days." Judging by Thomas Jefferson's temperature readings at Monticello in the Virginia foothills, the weather at Mount Vernon was not that cold. On December 15 at Monticello, it was 41 at 4 pm, 36 on the 16th and 41 on the 17th. It was cold the day he was buried on the 18th, only 22 at 4pm at Monticello.

As well as having a false premise, Thornton's story contradicts what he actually said to the mourners. Tobias Lear wrote in his diary that he wanted to delay the burial so more members of the family could attend, but Drs. Craik and Thornton insisted that because of the inflammatory nature of Washington's illness, there could be no delay in his burial. In that day, it was thought that death did not still the corrupting powers of some diseases.(21) page 225

His fantasizing about resurrecting his patron can be counted a resolution of his grief in the late stages of Thornton's life-long mourning of his loss. A more immediate reaction to his patron's death seemed to have been a sudden urge to design houses. Within a few months, beginning in February 1800, Thornton designed a mansion for himself in Square 171, a stables for Thomas Law, a boarding house for Daniel Carroll and his brother, a country seat for Lawrence Lewis and a church for Bishop John Carroll in Baltimore, all before August. All of those efforts were clearly documented in daily entries written by Mrs. Thornton in the diary she began keeping on January 1, 1800.

That burst of activity is cited as evidence that Thornton designed the Octagon. As Ridout puts it, "If Mrs. Thornton's detailed diary for the year 1800 is any indication, Thornton would have been pleased to respond to the opportunity to produce a design for Tayloe, fitting it into quiet afternoons and evenings between his work routine as a commissioner."(22)

Ridout and others cite what Thornton did in the future as a prologue to what he did in the past. What he did in 1800 winds up being evidence that he designed a house for which work began in 1799. Thus, Mrs. Thornton's 1800 diary became evidence that he designed the Octagon even though she never mentioned that in her diary. Judging from what she wrote in her diary, her husband and Tayloe shared their mutual interest in horses, not houses.

Her diary was devoted to her husband. In her March l entry, Mrs. Thornton observed that: "This little Journal is rather an account of my husband's transactions than mine, but there is so little variety in our life that I have nothing worth recording, and this may rather be called a memorandum than a Journal."(23) Unfortunately, she was not disposed to write about the emotions and motives of her husband, much less her own. That obliges one to interpret almost every observation she made.

For example, after dinner on Saturday, on January 4, the Thorntons and Mrs. Brodeau went by carriage to view the "General's houses." It would be a mistake to interpret this as end of the weekend chore that Thornton had performed since work began on the house in April. He would not make other Saturday visits. The day before, a message had come from Mount Vernon "requesting information respecting the General's two houses." That likely had to do with payments to Blagden. Yet, after Saturday afternoon dinner, Blagden was likely not at the houses.

In her diary, she never discussed their reactions to the death of Washington or their grief. Certainly in Thornton's life, no man had been more important. The whole nation was stunned and grieving. Congress set February 22, 1800, as a day of national mourning. One has to be careful when interpreting what people did in the wake of Washington's death as exemplifying typical patterns of behavior.

Then, on January 4, after visiting the General's houses, the Thorntons went to the Capitol where "we stayed for some time by a fire in a room where they were glazing windows while Dr. T-n laid out an oval round which is to be the communication to the Gallery of the Senate room."(24)

This would be the only mention in the diary of Thornton actually working inside the Capitol. In page 226 all the bickering over the work done in the building, no one ever alluded to Thornton actually doing anything inside the building.

She didn't describe their visit to the houses and Capitol as being in anyway solemn.

However, is it possible that Thornton's taking his wife and mother-in-law there was a way to share his mourning for his patron and friend? Or was he merely keeping in touch with the Capitol that he thought he had designed?

On Tuesday, a beautiful day, the Thorntons went to see Tayloe's house. Mrs. Thornton wrote in her diary: "After dinner we walked to take a look at Mr. Tayloe's house which begins to make a handsome appearance."C. M. Harris characterizes that and the other six visits they made to house in 1800 as evidence of Thornton keeping tabs on the progress of the house he designed. However, in those six other visits, she wrote nothing about the house. She never went inside the house, save in December to see chimney pieces that had just arrived from London.(25)

The commissioners' records prove that her admiring the walls of Tayloe's house on January 7th was not her haiku to the genius of her husband's design. He had another reason to look at the house that day.

The commissioners received a letter from Navy Secretary Stoddert reporting that the president planned to ship his furniture to the city in June. What prompted the page 227 president's announcement were the November 21 letter from White and Thornton and the December 13 letter from White. Adams bristled at being told where he might have to stay and jumped to the conclusion that the commissioners wanted to park him in George Washington's Capitol Hill houses.

He told Stoddert to tell the board that he would not stay there and insisted on moving into the President's house. Stoddert so informed the board. Clearly, he was also not interested in the other houses White mentioned. (28)

White was not in the city on January 7 when the letter came from Stoddert. Evidently, he had not told his colleagues what he had written to the president. Commissioner Scott had not signed the November letter. He was often too sick to conduct business. Stoddert's letter gave him the impression that White had asked the president to choose a house to be rented. Scott dashed a letter off to Stoddert disavowing the very idea of not using the President's house: "We hold it highly dishonourable to violate that faith which was pledged to the City Proprietors when they relinquished their property for a City—." Thornton also signed that letter. White would not take being accused of being dishonorable lightly.(29) The affair at least proved Cranch's 1797 description of Thornton as the vacillating commissioner.

Scott likely got Thornton to reveal what houses he and White had in mind. Scott knew that Tayloe's house would not be finished, and was likely not planned to be finished, until the fall of 1801, when, if elected, Tayloe would take his seat in the new congress. Scott had sold the lot to Tayloe and likely knew that it could not receive the president's furniture in June 1800. So, Thornton who evidently thought the house could house the president that fall, took a walk to see what state the house was in.Then on Sunday the 12th, the Thorntons took their friends the Peters for a brief tour of Capitol Hill. Mrs. Thornton's diary entry describing the visit is cited as evidence that Thornton designed Law's house. As Pamela Scott puts it: "It was designed by William Thornton, and was 'a very pleasant roomy house' according to Anna Maria Thornton." C. M. Harris opines that "Thornton's role...is partially but substantially documented by his wife's diary for 1800.."(26)

Actually, her diary entry shows that Thornton neither liked

nor understood the essential design element of the building. The purpose of the visit was clearly not to check up on his projects. The Peters lived in Georgetown and were probably not that

familiar with Capitol Hill. He was one of the executors of Washington's

estate. She was the sister of Mrs. Law. They both might have a say about

where the remains of George Washington and his wife would be laid. Thornton wanted to entomb them under the Capitol's yet to be built dome.

Then the full diary entry doesn't suggest that Thornton designed Law's house:

Sunday

[January] 12th— A very fine day, as pleasant as a Spring day. After

breakfast Mr T. Peter called and mentioned that his wife was at home; we

therefore sent the Carriage for her. I, and Dr T— . accompanied them to

the Capitol, the General's and Mr Law's houses —the latter being

locked we entered by the kitchen Window and went all over it— It is a

very pleasant roomy house but the Oval drawing room is spoiled by the

lowness of the Ceiling, and two Niches, which destroy the shape of the

Room.— Mr and Mrs Peter dined with us and returned home early in the

afternoon some of her Children not being well.(27)

Mrs. Thornton's criticism of the room was so succinct that one suspects that her husband informed it. If Thornton hadn't been in the room when Law showed it to the General in November 1799, then Law certainly told Thornton about the General's reaction to the room. That, and seeing the room built, may have revised his opinion of the "Ingenious A" who built it. The room was not strictly by the book. In large mansions or monumental buildings, a high domed ceiling usually looked down on an oval room. That was impossible in a five story town house in which Lovering carefully detailed the height of each room in the contract and built the house for $5800, almost half of the expense of Washington's houses and $7,200 less than the contract price for Tayloe's house. Mrs. Thornton would have other opportunities to reveal that her husband designed Law's house, but she didn't because he didn't.

Mrs. Thornton mentioned Tayloe again toward the end of January, but not in connection with his house. He is first mentioned on January 24. The day before her husband had spent the night with Philip Fitzhugh in nearby Virginia and did some horse trading. Fitzhugh offered "some land in Bottetcourt County, Virginia,...for half" of Clifden, one of Thornton's imported horses. Instead, Thornton made a deal to let Fitzhugh keep a filly and raise her foals.

While at Fitzhugh's house, Thornton got a note from Tayloe asking him to meet at the Union Tavern in Georgetown. After tea time on the 24th, Mrs. Thornton saw her husband when he was on his way to see Tayloe. He was back home at nine in the evening. Tayloe had to leave "very early in the morning for Annapolis."(30)

Mrs. Thornton's diary doesn't report on what her husband and Tayloe discussed. A brief meeting between tea time and 9pm in Georgetown left no time inspect Tayloe's unfinished house. Nothing that she described her husband doing in the next few days had anything to do with Tayloe. In February, Tayloe sent a letter from Annapolis about the legal status of a house Thornton's brother-in-law's wife owned in Georgetown. Then in her February 16 entry, Mrs. Thornton mentioned that their imported horse Driver was going to be sent to Tayloe in Virginia to be trained.(31)

For the remainder of her 1800 diary and the sparer notebooks that she kept from 1803 to 1815, she doesn’t mention her husband having had or having anything to do with Tayloe’s house. Her diary does not provide a mirror back in time revealing her husband's mastery of house design. But it does give some clues as to why on February 1, he finally designed a house. The death of Washington was likely the catalyst.

Thornton had long anticipated his death. In 1793, he suggested a memorial to Washington page 228 as the focal point under the dome. But when he got back to the city after the funeral, he realized that no one seemed to remember that. He wrote a letter to John Marshall, then in congress, whom he had never met. He knew from the newspapers that Marshall had chaired the joint House and Senate committee on Washington's death. It resolved that his body be placed in "a marble monument in the Capitol."

Thornton used rhetoric framing what congress had resolved as fulfilling his expectations: "I doubted not they would deposit his body in the place that was long since contemplated for its reception; I accordingly requested it might be enclosed in lead. It was done, and I cannot easily express the pleasure I feel in this melancholy gratification of my hope that the Congress would place him in the center of that national temple which he approved of for a Capitol." He added, "It will be a great inducement in the completion of the whole building, which has been thought by some contracted minds, unacquainted with grand works, to be upon too great a scale." Then he got to the point of the letter and touched on a matter no one else had. He suggested that congress pass a bill in secret assuring the eventual burial of Mrs. Washington in the temple. He added that he wrote "unknown to any of the family."(32)

In his letter, he didn't mention that he would design a memorial under the dome. He hoped that Marshall took that for granted. However, coming up with a design for a tomb was not easy. It wasn't until late February that he shared his ideas in a letter to Blodget. Thinking about his design likely filled his winter evenings. Mrs. Thornton did not observe thoughts in her diary but she did reveal that on January 9 "Employed myself in copying from [a book of Gothic ornaments] and cutting pieces respecting General Washington out of the newspapers, to put together in a book."(34)

Then Thornton was rudely reminded of another president and his future place in the city. On January 20, Benjamin Stoddert wrote to Thornton castigating the commissioners for not properly preparing the President's house for the reception of the president: "A private gentleman preparing a residence for a friend would have done more than then has been done," Stoddert wrote and he wanted an enclosed garden similar to one had by the richest man in Philadelphia, William Bingham. There also should be a stable, carriage house and garden house. The latter should be in a garden that would be "an agreeable place to walk in even this summer."

On January 30, Thornton wrote back that he had always been for grandeur throughout the city. His colleagues had always dragged their feet: "They are however afraid of encouraging any expense not absolutely necessary, and seem not to think these things necessary that you and I deem indispensable." He then reflected on the mansion: "Some affect to think the house and all page 230 that relates to it are upon too extravagant a scale. I think the whole very moderate,..." He added that the president should get a salary of $100,000 to maintain it. At that time he made $25,000.(35)

Thornton also sent a plan of the President's house to the president and noted that "the colonnade to the south is not completed at present, and temporary steps are to be put in." As a president looked south from his mansion, he would see lots Thornton owned at the east end of Square 171.(36)

Two days later, according to Mrs. Thornton's diary, Thornton designed a house for Square 171: "Saturday, Feby 1st a fine day. The ground covered with the deepest snow we have ever seen here (in 5 yrs.) - river frozen over. Dr. T- engaged in drawing at his plan for a House to build one day or another on Sq. 171." On February 4, 1800, she noted: "I began to copy on a larger scale the elevation and ground plan of the house."(37)

Mrs. Thornton did not give any clue as to why Thornton designed the house. He had bought the lot in May 1797. He had first bought lots in the city on Peter's Hill in 1794 and in 1795 claimed to have discussed plans for building there with the president who owned lots nearby. He was awarded the lot next to Washington's in October 1798, and had promised to build there. Yet, there is no evidence that he designed a house for a lot he owned until February 1800. Between 1794 and 1800 there had been other snowy days, yet Thornton did not get the urge to design a house.

The death of the General forced Thornton to focus on a tomb inside the temple under an oval dome. His imagination pulsed with ovals. Perhaps,

the death of the General as well as the handsome appearance of Tayloe's brick wall brought home how he had miscalculated. He had

come a Cadmus to build a city, but designing its greatest building was

not enough. Even the General had not asked him to design his houses. No one seemed to expect him to design the marble memorial for General.

Then, writing from Philadelphia where a tomb for the General outside of the Capitol was a lively topic, Samuel Blodget asked Thornton if he had any ideas. Thornton began his reply on February 21, and tried to reveal what he had been thinking about for weeks. That proved a hard day to write about his friend. According to Mrs. Thornton, Georgetown and Washington would muster 1,000 people to church on February 22, a national day of mourning. On the 24th, Thornton resumed writing his reply and described his design for a tomb. He reminded Blodget that he had served the departed and "can scarcely think on the subject without having all my ideas absorbed in the loss of my great patron."

But he had an idea and even made a sketch of it at the end of the letter. That sketch outlined "a fine group of figures on a well composed massy rock." An image he saw at the Antiquarian Society in Edinburgh of a bronze statue of Peter the Great "on horseback, the horse rearing, on top of an enormous rock of granite" gave him the idea.

|

| 149. 1782 engraving of Peter the Great on a horse and mountain |

page 229 Thornton pictured the tomb as a jagged rock surrounded by "the arcade supporting the colonnade round the dome," which "wou'd give such a contrast as to make the whole a grand and striking composition. The dome also being lighted in the center would be admirably calculated not only to render the principal figures more bright but wou'd give more apparent reality to the design of the figure of Eternity."

|

| 150. Thornton's massy rock monument |

The bodies would "be deposited in a place prepared in the rock, in the region where Time and the rest of the figures are grouped, signifying that tho' time has taken possession of his body, yet Eternity has taken his spirit out of the reach of time."(33)

What a difference a year made. In 1799, he excused himself from making drawings to assist Hoban's effort to make the North Wing convenient and credible. Invited to participate in the General's building project, Thornton played architecture know-it-all and touted a development scheme. In the cold winter of 1800, he was afire with a mountain monument and ovals. But if this was a new Thornton, why didn't his wife celebrate it? Her copying the floor plan and elevation of the house gave her no joy. The house was something "to build one day or another." As for the monument for the General, she commented "Dr. T- wrote to Mr. Blodget in answer to a letter requesting his opinion concerning a monument to erected some future day in the Capitol."

It bears noting, that her downbeat attitude was not what one might expect if in previous years her husband had made plans that had materialized as Law's or Tayloe's houses. W. B. Bryan offers an interpretation for her lack of enthusiasm. She knew the house could not be built "owing, no doubt, to a lack of funds, which was a common experience in the life of a man who moved in a large orb, but one not within in the range of either the making or the saving money."(38)

There is something to that, but at the same time, Mrs. Thornton and certainly her mother were well aware of the considerable amount of money Thornton would make when he sold his Lancaster property when his aunts died or no longer needed the property. In an 1823 letter to James Madison, Thornton recalled that he thought the Lancaster property was worth $40,000. The death of his mother in October 1799 might lead to some reckoning of the Tortola estate with money coming to Thornton. (39)

page 231What likely dampened her enthusiasm was where her husband planned to build. For the mutual profit of the original landowners, David Burnes in this case, after the surveyors divided the city's squares into lots, the owner and commissioners divvied up the lots 50/50. The prospects of anyone building on Square 171 seemed so slim that the commissioners let Burnes have all the lots in the square. When the Thorntons walked down New York Avenue and saw Tayloe's handsome wall, they walked by their lots in Square 171. To their left was the crest of the gully leading to the confluence of Goose Creek with the Potomac River.

| |

| 151. Above early 19th century topographical map, below Hawkins 20th century reconstruction of same area, |

Not only did the square need to be leveled but all the ground to the east of it was brambles and scared by erosion. The only thing Thornton would do to his part of the square was to have part of it fenced by his slaves and planted with buckwheat. After what she wrote in February, Mrs. Thornton never mentioned the possibility of building a house there.(40)

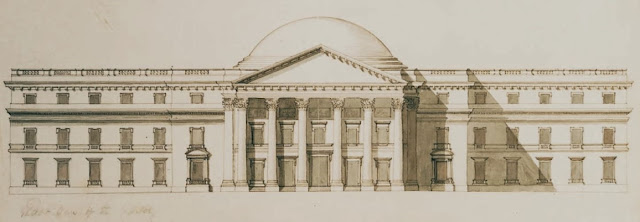

The terrain of the square which defeated the likelihood of Thornton building there pinpoints the lot for which he designed a house. Thornton had bought several lots: 1 to 5 and 15 to 21 on the southern and eastern border of the square.(41) Judging from the topographical shading of an 1800 map of the city, the only sensible place to build was on the lot at the intersection facing the President's house, lot number 17. His other lots in the Square were not as accessible. That left Thornton with the same problem that the architect of the Octagon and Law's house had solved. That meant he could copy Lovering's solution and out do it with a nobler house.

|

| 152. Lots in Square 171 |

However, there was aspect of the lay of the land that likely seduced Thornton into buying lots there. Once cleared of brush, one could look down the slope and see the Potomac. Thornton could see the emerging mud flats that he hoped to one day claim. Thanks to the slope from a house on the lot forming the northeast corner of the square, one could look to the south and still see the Potomac. At the same time, from the northeast lot one could build a house almost fronting the President's house. What attracted Tayloe to Lot 8 in Square 170 was that it was large enough to accommodate a stable and exercise yard horses behind the house.

The

design for Square 171 now in Thornton's papers and mistaken as a

preliminary design for the Octagon could not have been a preliminary

design for a house in Lot 8 in Square 170. That the large oval room at the rear of the house looked out at the stables and yard where slave grooms could prove only to themselves that the master's horses loved them best. Tayloe's stable of horses was famous. Any would be house designer, especially an aspiring breeder like Thornton, should have known that.

Thorton's

February 1800 design was an elaboration of Lovering's design for

Tayloe. Doing that was more in Thornton's character than paring down a

design to suit Tayloe's needs. The process that Ridout suggests happened

sometime between April 1797 and May 1799 was actually reversed in 1800.

Based on what Thornton saw of the Octagon.

with particulars elucidated by a specimen from Lovering, page 233

Thornton came up with his own design to suit a similar lot.

The oval room at the rear of the house afforded a view of the Potomac River. The large semi-circular porch invited eyes looking down from the President's house.

Then why didn't Mrs. Thornton mentioned all that in her diary? On the rare occasion that Mrs. Thornton mentioned her husband's architectural plans in her diary or notebooks, with one exception, she never described or characterized what he drew. One gets the impression that she was not overly impressed with his designs. After all, they were few and far between. After his many 1800 projects, she noted that he drew a house plan in 1808 and 1811.

In 1800, she also didn't mention Lovering's floor plan guiding her husband. However, one can resort to the same future is prologue logic employed by those who credit Thornton for designing the Octagon because of the ease with which he drew designs in 1800. On May 1, 1811, she noted that Lovering, who then lived in Baltimore, dropped off a book for Thornton. The next day, Mrs. Thornton noted that her husband was "drawing a plan for a house."(42)

However, her lack of commentary about his house plans doesn't excuse her not mentioning her husband designing the Octagon. A few weeks after writing so little about the house design for Square 171, she wrote at greater length about plans he drew for Thomas Law's stable.

Go to Chapter Fifteen

Footnotes for Chapter Fourteen

1. GW diary

2. Turner to WT, 2 June 1799, Harris, pp. 497-9; Minutes American Philosophical Society. February 21, 1800, March 21, 1800.

3. WT to GW, 31 May, 1799, ; Walker to GW, 5 August, 1799,

4. Thomas Adams to Abigail Adams, 9 June 1799,

5. Lear to WT, 12 September 1799, Harris, pp. 508-9

6. WT to GW 19 July 1799, ; GW to WT, 1 August, 1799.

7. Law to GW 10 August 1799 GW to Law 15 August 1799 ; GW to Law 21 September 1799: "I had a desire (not a strong one) to possess the corner lot belonging to Mr Carroll on New Jersey Avenue, merely on account of its local situation; but have ⟨abandoned⟩ the idea. Disappointed in every expectation of receiving money, though most solemnly assured it, I am obliged to have recourse to borrowing from the Bank of Alexandria—much against my inclination to carry on my buildings in the City."

8. WT to GW 1 September, 1799, Pickering lost a son to the 1793 epidemic

9. Mrs. Thornton's Diary, page 129, 14 April 1800

10. on William Hamilton

12. GW to Lewis, 20 September 1799

13. WT to Law, 1 August 1799, Harris p. 505

14. GW's diary

16. WT to Lettsom 26 November 1795, Pettigrew 2 pp 549-55

17. Law to Greenleaf, 9 April 1800, Adams Papers

18. GW's diary

19. Commrs to Adams, 21 November 1799; White to Adams 13 December 1799 ( the editors of these on-line papers transcribed "Taylor" but the letter clearly reads "Tayloe.")

20. GW to White 8 December 1799

21. GW to WT 8 December 1799, Jefferson's weather observations , page 25; Lear Journal, Clements Library. Harris, p. 528; Thornton did not date his brief recollection of his patron’s death. However, in it he described Thomas Law as the brother of Lord Ellenborough. The latter Law became a Lord in April 1802 and died in 1818.

22. Ridout p. 29-30, 61

23. Mrs. Thornton's Diary, p 113.

24. Ibid pp 90-1.

25. Ibid p. 92.; Harris, p. 585.

26. Creating Capitol Hill, p. 129; Harris p. 586

27. Op. Cit., p. 102

28. Stoddert to Commrs.

29. Commrs to Adams, 7 January 1800; White to Adams, 15 January 1800,

30. Mrs. Thornton's Diary p 99.

31. Ibid. p. 107.

32.WT to Marshall, 6 January1800, Harris p. 526-7

33. WT to Blodget 21-24 February 1800, Harris p. 535ff

34. Mrs. Thornton's Diary, p. 93

35. Stoddert to WT, 20 January 1800, WT to Stoddert, 30 January 1800, Harris p. 532-3

36. Ibid. p. 533.

37. Mrs. Thornton’s Diary, p. 102

38. Bryan, History of National Capital, vol. 1, p. 346; Diary pp. 110-1.

39. WT to Madison, 2 September 1823

40. Commrs. records improve land east of 17th street; on division of square with Burnes see Surdocs Record Book

41. Clark, "Doctor and Mrs. Thornton" p. 167

42. AMT Papers, vol. 3, image 121

Comments

Post a Comment