Chapter Fifteen: Mrs. Thornton's Diary and All of Thorntons Horses

Table of Contents page 235 Index

Chapter Fifteen: Mrs. Thornton's Diary and All of Thornton's Horses

|

| 154. Mrs. William Thornton by Gilbert Stuart 1804 |

On Sunday, February 16, 1800, Thomas Law called on the Thorntons and the talk turned to houses. In her diary, Mrs. Thornton noted how pleased Law was with his new house; no mention of who designed it. Law talked about another house he planned to build to board nine congressmen and Vice President Jefferson; no mention of his asking Thornton to design it.

Then on February 27, "Dr. T- received a note from Mr. Law enclosing a rough Sketch of a plan for a Stables & c. behind his house which is five stories before and three behind, which Dr. T- had promised to lay down for him as he had suggested the ideas - The Stables and Carriage house are to be built at the bottom of the lot and the whole yard to be covered over at one Story height, and gravelled over, so as to have a flat terrass from the Kitchen story all over the extremity of the lot.... Dr. T- engaged in the evening drawing Mr. Law's plan." And that was that. There is no more mention of the plan. It is not certain what Law built, but the boarding house page 236 would advertise its ability to board 60 horses.(1)

When quoted in full, Mrs. Thornton's January 12 description of walking through Law's new house doesn't prove that her husband designed that house. But what Thornton did for Law at the end of February conclusively proves eagerness and facility for designing buildings other than the Capitol.

In March she jotted down more clear proof that he designed houses for other people.

On March 4, Thornton went to Mount Vernon where he bought two "she asses," ordered shad to be brought up to feed the hired slaves in the city, and received a gift of brandy from Mrs. Washington who said the General intended to give him the barrel. Just before Thornton left on the morning of the 7th, he went out "with Mr. Lewis to see the situation on which he is going to build on the Mt. Vernon estate - and to mark the trees he ought to cut down & c."

In her

August 4 entry, Mrs. Thornton would note: "Dr. T has given him

[Lewis] a plan for his house. - He has a fine situation all in woods, from which he will have an

extensive and beautiful view." Construction

did not begin until 1802 and the Lewises did not move in until 1805.

Architectural historians are not impressed with

Woodlawn. As C. M. Harris puts it: "The house as it appears today

bears no resemblance to Thornton's other designs; it is a handsome

but thoroughly traditional structure in the American Georgian

style."(2)

Which is to say that it was not at all like the Octagon and Law's

house that Thornton very likely didn't design. But it is proof that he did design houses.

|

| 155. Woodlawn |

Back to 1800: On March 12: "while we were at breakfast a boy brought a note from Mr. Carroll of Duddington, (living in the City an original and large proprietor) requesting Dr. T- as he had promised, to give him some ideas for the plan of two houses he and his brother are going to begin immediately on Sq. 686 on the Capitol Hill." Thornton spent the afternoon "drawing the plans for Mr. Carroll."

He worked on the plans the next afternoon, and the next day, he brought Carroll home to show him the plans "with which he was much pleased." And that was that. That page 237 Thornton had a ready model for Carroll's two houses in Washington's two houses, doesn't lessen the significance of his evident facility for a more complex house design. He was proud of what he had done for Carroll. On Sunday March 30, 1800, with a friend, the Thorntons "walked to see Mr. Carroll's houses." On January 5, 1801, Carroll's brother offered the houses for sale and his ad described them as "finished in a plain but substantial manner, and built of the best materials."(3)

There is one more Thornton design in 1800 that wasn't built. On March 22, just as Thornton was about to make a plan for beautifying the grounds around the President's house, "Mr. [Notley] Young's servant brought a letter from Bishop John Carroll at Baltimore requesting Dr. T - to draw a plan for a Catholic church which is to be built in Baltimore, they already have several plans but don't like any of them." Young was an original proprietor married to Bishop Carroll's sister. Her other brother, Daniel, had been a commissioner. Daniel Carroll of Duddington was their nephew.

|

| 156. Bishop Carroll in 1804, by Stuart; a good reason to show this is that there are no portraits of his older brother Daniel the commissioner |

Young's mansion overlooked the Potomac. Thornton went there to find the priest who brought the letter to get more information but couldn't find him. The next day he wrote to Bishop Carroll. He did not begin working on a design until April, worked on it off and on through summer. After missing one appointment, the bishop finally came to look at it, and eventually took a design made by Benjamin Latrobe.

|

| 157. 1907 photo of cathedral designed by Latrobe |

page 238 True to form, Mrs. Thornton did not reveal any emotions experienced by herself or husband during a summer of creation ending in rejection. On August 24, the bishop came for tea and to see the drawing of the church. She wrote, "The bishop was much pleased with the plan and took to consider it for a day or two." There is nothing else about the church or bishop in the rest of her diary.(4)

The demand for Thornton's architectural talents was short lived. Both Law and Daniel Carroll continued to build houses in a vain effort to profit off their many building lots in the city. Other men, including Hoban, designed their houses. There is no evidence that they again asked Thornton for building plans.(5)

|

| 158. Carroll's Row after Civil War |

In February and March 1800, both Law and Carroll had a reason to flatter Thornton. Through her

nephew William Cranch, who was then Law's lawyer, they likely learned

that

Mrs. Adams had doubts about moving into the President's house. She

feared the building would be too green.

Law wrote the letter to James Greenleaf already quoted that described his house and asked him to see that Mrs. Adams got the letter. Carroll sent a letter to Cranch describing his page 239 house, and Cranch sent it to her.(6) With moving into Tayloe's house out of the question, that left Law's and Carroll's house in the running. Having Thornton on their side could do neither Law nor Carroll any harm.

There was another reason to flatter Thornton. Law and Carroll had long been promoting the eastern side of the city. Despite his design of the Capitol, Thornton never became a familiar face on Capitol Hill until he helped Washington pay the contractors building his houses. By February 1800, those houses were finished. What better way to keep him interested in Capitol Hill than by involving him in other projects there.

Once the federal government began moving into the city in June, the commissioners became less important. There were diminishing returns for any flattery of Thornton.

At the same time, there were no returns for Thornton. He never explained why he did not ask for a fee for his designs. Did he see through his own boasting and understand that his designs could not actually be built? That's not likely. Did taking a fee violate his conception of a gentleman? He would bargain and sale with regards to horses. He would scheme to profit off his patents.

In 1799, Thornton wrote to his old Quaker friend Thomas Wilkinson describing how he handled Washington's money "as a friend." In her diary, Mrs. Thornton did not delve deeply enough into their lives to develop that theme. His use of the phrase in a letter to a simple Quaker poet who once was his best friend could be taken as a way to assure him that he had not become a money changer. However, in her diary his wife used the same phrase. He superintended the contractors "as a friend." It was a phrase he must have proudly shared with his wife. Evidently after his great friend died and perhaps to assuage his regret at not being asked to design the General's house, Thornton decided to share his architectural genius as a friend.

Prior to August 1799, there is no evidence that Thornton and Tayloe were friends. And judging from Mrs. Thornton’s diary, there is no evidence that Thornton had any interest in the progress on Tayloe’s house per se. In November, he did get excited by its imported chimney piece made with artificial stone. Thornton had scouted a display of chimney pieces at Tunnicliff's hotel back in May, evidently for the North Wing. The Thorntons did take visitors to see the outside of the house, which was also near to lots they owned. However, in late March, the Thorntons took a friend to see work on the Capitol and Carroll's two houses, but even though Mrs. Thornton took her to see the work on the Executive Office, she didn't show her Tayloe's handsome house which was a few blocks away.(9)

In an entry she made the day after her husband sent his February 15 letter to Tayloe, she noted her husband's dealings with Tayloe: "We have twenty-three horses - 17 at this time at the farm - one lent to Mr. Brent - one sent to Mr. Fitzhugh to keep on shares - Clifden now here to be sent to Mr. Sam Ringgold - Driver now at the farm to be sent to Mr. Tayloe's in Virginia to run."(10)

A

late winter interest in horses does not prove that Thornton did not

design the Octagon. But as summer approached, in his wife's diary, there was great

anticipation about horses and almost none about houses.

Joe set off early this morning to accompany Randall Mr. O'Reilly's boy (whom Dr. T. engaged, letting Mr. O'R- have another during his absence) to stay at Mr. Tayloe's Mount Airy, Virginia, to train Driver. He also took the Sorrel filly; is to go as far as Neabsco near Dumfries and return to morrow. He rode one of the carriage mares. He took a letter from Mr. Tayloe to the manager of his iron works at Neabsco directing him to send a man with Randall to his seat. Took with them corn, bread and meat to save tavern expenses. After breakfast Dr. T went to the [commissioners'] office, I worked on my screen, mama quilting. Dr. T wrote a letter to Mr. Lewis, to request to him to purchase some provisions on account for the two asses he bought at Mt. Vernon because he could not make it convenient to send for them immediately.... Dr. T worked all day on Mr. Carroll's plans - I read-

Joe and Randall were slaves. The letter Joe carried from Tayloe was a better guarantee of passage through Virginia than the usual pass written by Thornton. Then one of Tayloe's slaves would escort Randall to Mount Airy. Randall was a jockey. Tayloe favored slaves as jockeys, which was congenial to Thornton. White jockeys who won races demanded more money. The Sorrel filly was going to Tayloe as part of a trade, but horse for horse, not horse for house design.(11)

Since January, horses had been a source of good news in Mrs. Thornton's diary. Thornton had sold a half share of a mare to Tench Ringgold, the most notable in a family of Maryland breeders, for 120 guineas or $600. That took on more importance because on March 24, Thornton got word that "the note drawn on Mr. Chorley of Liverpool" was protested. Chorley was the agent for the sugar plantation in Tortola that Thornton half owned. The upshot was that Thornton had to cover the bounced check and pay a penalty. That made the annual payment on his Maryland farm problematic.(12) However, sales and trades of horses did not save the day financially. They had only one horse that had a chance to win a race, Driver.

Meanwhile, the federal city finally came to life. Bureaucrats came first followed by the president who made a short visit. He always spent the summers at home in Quincy, Massachusetts. He came to the city in June after congress adjourned in Philadelphia for the last time. By way of pomp, John Adams was an intimidating presence. After making what today would be called campaign stops in Pennsylvania and Maryland, he toured the federal city in his chariot and four. (President Washington had usually been on horseback when he toured.) Adams' local supporters clung to him like slugs on a pumpkin. He would appoint many of them to local offices. Hosts of dinners and meetings to honor the president all invited Thornton.

Thornton found his moment with the president who, according to Mrs. Thornton's diary, expressed an interest in seeing the plans for the Capitol at 1pm the next day. At 2pm the presidential chariot and four thundered by Thornton's F Street house and didn't stop. Thornton saw the president that evening at a dinner hosted by Uriah Forrest. The president said he had been too much engaged to stop. Thornton joined the retinue that followed the president throughout his visit. He told his wife how Adams disappeared in the middle of one event designed page241 for all to socialize with him, and wound up at Tristram Dalton's house.(13)

On June 18, 1800, four days after the end of President Adams's nine day visit to the city, his cabinet remained behind in the city that was now their home. Mrs. Thornton oversaw preparation for a dinner for twelve including three cabinet secretaries: State, War and Navy. In a sense, at that dinner, Thornton reached the pinnacle of his career. In a 1794 letter to Lettsom, he had explained that "the trust reposed" in the commissioners "is so great that I do not know of a more extensive power in any offices of our government, except the President, or perhaps the Secretary of State, Treasury and War." At his table, joining influential locals, only Treasury secretary Wolcott was missing. Commissioner White came after dinner. The ever ill Commissioner Scott did not come. Secretaries Marshall and Dexter had been in office for only a few months. That likely increased Thornton's sense of his own importance. He had been in office for almost six years, almost as long as Wolcott.(14)

That Wolcott missed the dinner party might have been for the best. After Thornton called on him, Wolcott wrote to his wife that Thornton had assured him that the city would have "a population of 160,000, as a matter of course, in a few years." (Sometime between 1870 and 1880 the population of the District of Columbia passed 160,000.) Then Wolcott added: "Their ignorance of the rest of the world, and their delusion with respect to their own prospects, are without parallel."(15)

There was also a shade cast on the party at least for the Thorntons by a note received before the gentlemen assembled. On a less busy day, Mrs. Thornton might have written more about it: "Driver returned from Virginia in the afternoon lame and in bad plight." Evidently there had been no letter from Tayloe warning them of this. For the rest of the year, she did not note any more letters from or to Tayloe. There was no more mention of trading or training horses with him.

Perhaps the best evidence that she lost her regard for Tayloe came in November. On the third, her husband went to the races in Alexandria. If Driver had survived Tayloe's handling, he might well have been entered into one of the races. Thornton returned on the 5th and Mrs. Thornton noted his doings: "He was at a play in Alexandria and all the time in company of the Treasurer, Mr. Meredith, whom went with him to dine at Dr. Dick's and Col. Sims, and they rode home together." Tayloe's horse won the feature race at Alexandria. If her husband told her that, she didn't put it in her diary.(16)

In

December 1800, she went inside Tayloe's house to see the chimney pieces made of artificial stone. She inspected them accompanied by two lady friends. It was likely her

first view inside the house. She wrote nothing about its interior,

let alone that her husband designed it.(17) page 242

|

| 159. Coade stone fireplace in Octagon Museum |

She did not mention her husband's reaction to Driver's bad plight. She did note the three days he contemplated the form of a famous horse. He worked on a drawing from a print of Eclipse. On August 24, she put it this way: "Dr. T engaged in copying a print of the Horse Eclipse. - Bishop Carroll came to see the drawing of the church." While Thornton could dash off house designs, his study of Eclipse took time. On September 3, he stayed up "very late" working on the drawing. On October 2, he worked on it again.(18)

Almost two years after Driver returned in bad plight, Thornton made his reaction to that public. On April 5, 1802, he placed a very long ad in the National Intelligencer extolling Driver, and blamed Tayloe for the horse's failure to win or even enter races. Thornton's ad was cast as a traditional offer of stud services, but it broke the mold by touting races that Driver lost:

Driver was never tried but once, by John Tayloe, esq., at Tappanoe in Virginia when the bets were in favor of the winner (Yaricot) distancing the field; but Driver lost one heat by only a few feet, and the other heat by only four inches, in three mile heats, distancing the other horses; which as Driver, like his celebrated sire, is a four mile horse, was thought a great race, especially as he was much out of order in consequence of a bad cough. Col. Holmes [probably Hoomes] told me he was thought by those who saw him run, one of the best bottomed horses in America, or perhaps in the world. Driver was put into training the last autumn, but met with an accident that prevented his starting; however, he proved one of the fleetest horses Mr. Duvall ever trained, and of ever lasting bottom.

By "bottom" was meant staying power and stamina. While the ad didn't blame Tayloe for sending Driver home in "bad plight," later in the ad, Thornton quoted Charles Duvall as saying: "if I had trained him at four years old, I think he would have made the best horse on the continent...." Which is to say, if Thornton had sent Driver to Duvall instead of Tayloe, then in 1800 Driver would have won the purse at Alexandria and shined as well in the Washington races in 1801, where, by the way, Tayloe's three horses lost. Thornton didn't offer Tayloe's opinion of Driver.

page 243 For an advertisement for stud services, Thornton's was very long. The rest of it also put Tayloe in his place. Thornton celebrated his English connections when everyone knew that Tayloe's connections were unparalleled. According to the ad, "the dam of Driver was purchased by my relation Isaac Pickering, esq., of Foxlease, Hampshire, England, who sent her to the Earl of Egremont's by one of his own grooms." That is to say, that when he bought Driver, Thornton did not need Tayloe's help.

Thanks to Driver's pedigree, Thornton could drop the names of the great men who owned Driver's blood lines: Lord Edgmont, Lord Offery, the Duke of Somerset as well as the Earl of Egremont. Tayloe knew the latter well. He would soon buy a farm outside the City of Washington and name it Petworth after the earl's seat in England. No reader would mistake mere name dropping as indicating a personal acquaintance, but the ad gave the impression that only the Atlantic Ocean kept Thornton and the earl from being best of friends. Thornton added that the individual pedigrees were examined in a stud book by Governor Ogle, who was Tayloe's father-in-law.(19)

Just as Thornton thought he bested trained foreign architects, he was confident that he could breed better horses than Tayloe who might be said to have been bred as a breeder. Stud services were generally offered in the spring. But if Thornton had designed the Octagon, why would Thornton throw down that gauntlet just when Tayloe's house was finally finished? Work ended on the Octagon at the end of December 1801.(20)

Thornton all but said that Driver would be the greatest horse in the country if he had not sent him to be trained by Tayloe. However, every horse breeder in America was envious of Tayloe. Thornton's public expression of that envy made no difference to Tayloe. New to the federal city, he was looking for friends, not rivals. He had not won election to the House. Not elected, not appointed, and not heavily invested, Tayloe had no reason to be in the city. Only 32 years old but too rich to pretend to be something he wasn't, he had nothing better to do than to be sociable and be of service. His closest friend in the city, Congressman John Randolph of Roanoke, was his arch rival on the turf. He had a biting wit and trigger-ready sense of honor. Tayloe maintained a long friendship. There is also no evidence that Tayloe ever lost his liking and respect for Thornton.

At the races, Tayloe was the cynosure of all eyes. That surely should have struck Thornton during the 1803 Washington City Races. Thanks to congress assembling in October instead of December, the crowd and excitement was enormous. House and Senate adjourned for three days so members could watch. A Massachusetts congressman counted 200 carriages, 800 men on horseback and "between 3000 to 4000 people black, white and yellow" from the president on down. While Tayloe's horses came in second, the congressman hailed him as the man of the moment worth $10,000 in horses alone.(21)

Thornton made his presence felt. According to Mrs. Thornton notebook, on October 24 his horses were sent to town from where they were being trained. On the 26th Dr. T went to the race ground; on the 27th he went before light to the race ground; on the 30th he went to the race ground after dinner; on the 8th and 9th they went to the races, he dined with the Jockey Club on the 9th; the races ended on the 10th and on the 11th the Thorntons had a roomful including Tayloe. But Thornton's horses didn't place in any of the races.(22)

page 244 Thornton would not let his rivalry with Tayloe end. On March 21, 1804, Thornton ran another long ad in the Intelligencer offering the services of his other imported horse, Clifden. The horse had not been wronged by Tayloe, and nothing in the ad could be deemed disrespectful of Tayloe. It glorified what Tayloe had been promoting since he came home from England, improving the American horse through breeding with horses imported from England. But the ad gave the impression that Thornton was better connected in England than Tayloe.

After recapping twelve races in 1792 in which Clifden

won ten, the ad digressed and discussed the triumphs of Clifden's

brother: "The duke of Queensbury's Mulberry, full brother to

Clifden's dam, beat... Lord Darby's Sir Peter Teazle over the Beacon

course, for 500 g's, and his lordship has since refused six thousand

guineas for Sir Peter, as stated in a letter to Dr. Thornton in

1800." Thornton didn't exactly say he learned that in a letter

sent to him by his lordship, but in the ad, Thornton did quote a

letter sent to him from a member of Parliament.

James Madison was impressed. He sent some of his mares to Clifden. In

a November 19, 1804, letter to him, Thornton recapped another side of

his breeding operations. He "let" his mares to foal

champions for other breeders, including one "by Driver out of

the full sister of Nontocka by Hall's Eclipse (imported) her grand

dam Young Ebony by Don Carlos, gt. Young Selima by old Fearnought;

gt, gt, gr: dam old Ebony by Othello; gt., gt. gt., gr: dam old

Selima (imported) by the Godolphin Arabian."(23)

Tracing a horse's pedigree back to Godolphin Arabian was the gold

standard. Thornton proved that he could do that with one of his horses as easily as Tayloe.

|

| 160. Godolphin Arabian |

Of course, it was evident to everyone else that they weren't equals. They were poles apart. Tayloe relied on an enormous stable to find the horse to cross the finish line first. Thornton propelled his chosen horse with rhetoric.

page 245 As for the social aspects, even in the local jockey club, Thornton found a niche rather below Tayloe's. In 1806, he was not one of the club's six officers listed under President Tayloe.(34) Instead, before the races, Thornton patrolled the grounds; at the races he kept the time. This is not to suggest that Thornton was Tayloe's consultant in practical matters. In 1810, when Tayloe decided that the roof of the Octagon had to be fixed, he hired Hadfield to redesign and rebuild it.(24)

Thornton assumed that major victories on the track would come, but they didn't. The October 1811 Jockey Club races made a laughing stock out of Thornton and his horse. A letter written by a young British diplomat captured the moment. Thornton's problem was that his jockey was over weight. He had given him "physic" to bring his weight down, to no avail. To lighten his horse's load, Thornton removed the saddle leaving the jockey with only a blanket. That slipped off during the race, the jockey lost control of the horse, which amused the crowd. A few days later, Thornton was too sick to go out.(25)

A few days before the race President Madison, who fancied good horses, invited both the Thorntons and Tayloes to dinner at the President's house. But Thornton did not take defeat gracefully. Just as he had to explain Driver's falling short, he had to rescue Eclipse Herod's reputation. He wrote an advertisement about the horse. After explaining the loss in Washington as the fault of an overweight jockey, Thornton gloried in what the horse did next:

In 1811 he ran again at Leesburg, Va., four mile heats, and won the race against Mr. Hansbury's (of Virginia) horse Walnut, Whitestockings belonging to Messrs. Smar and Murray of Virginia; but the purse was denied him under the charge of foul riding. This was the fifth time he won the first day's Jockey Club purse at Leesburg without losing a race running the four mile heats against some of the best horses in Virginia. In 1812 he won the first day's purse, four mile heats, at Libertytown; beating the famous running horse Redbird, Mr. Darnall's horse Singecat, and Mr. Griffith's mare from Virginia raised by Col. John Tayloe...(26)

That Thornton singled out a nameless mare vanquished by Eclipse Herod as having been raised by Tayloe goes beyond the usual niceties of identification. Friends can be rivals, but what is the point in competing in such a petty way with a close friend and the richest and most successful horse breeders in America? Tayloe didn't seem to notice, and they shared the turf in other ways. On November 14, 1811, Thornton sent 40 ewes to Petworth, Tayloe's local farm, and 20 more the next day. Thornton's latest enthusiasm was raising Merino sheep.(27)

The

celebrated horse Rattler acknowledged by the best judges in Virginia,

where he was bred and ran with so much success, to be the finest young

horse of his day, page 246 having lost his race yesterday and having won in great

style in Annapolis the last week, it was thought proper to publish the

result of an examination made by the judges which is printed below: "We

have examined Dr. Thornton's horse Rattler, and find his near fore

postern joint swelled, and the main sinew much enlarged and swelled, so

as to render him lame."(28)

Then Thornton refused to pay for the horse. The seller Col. William Wynn sued for the $3,000 Thornton promised to pay. Testimony at the trial suggests that Rattler's 1821 run at the Jockey Club Races was the climax of Thornton's rivalry with Tayloe. The seller "declared" the horse to be "capable of beating any horse in the United States" and "recommended the purchasers to match him against a celebrated race horse in New-York called Eclipse."

.jpg) |

| 161. American Eclipse |

Thornton lost the race in Washington the day after Lady Lightfoot lost to Eclipse at the Union Course on Long Island. She was the pride of the South bred by Tayloe and she had a 31 race winning streak.(29) A victory by Rattler in Washington might have assured a match race with Eclipse and Thornton's horse could have saved the reputation of Southern horses.

Thornton

and others testified that Rattler horse was in terrible shape when he

bought it. Wynn and others testified that Thornton starved the horse

over the winter. The judge ruled that the jury

should not consider the condition of the horse, and Wynn won the case.

According to one of Tayloe's sons who was at the trial. John Randolph of

Roanoke immortalized the trial with an "impromtu;"

With his horses unfed, he loses his races

With his lawyers unfeed, he loses his cases(30)

page 247 Thornton appealed the case, and also kept Rattler. In 1822, a broadside advertised "Rattler belonging to Dr. Thornton" as a stud. It described him "as the best on the continent," equaling Tayloe's Sir Archy. Not only was Rattler gotten by Sir Archy but his dam Robin Red-Breast traced her pedigree back to old Highflyer just as Sir Archy did. Ergo, Rattler's pedigree was better that Sir Archy's because of a "double cross... Rattler is doubly descended from old Highflyer."(31) If Thornton couldn't beat Tayloe on the track, he could beat him as a stud, despite the Tayloes having had six children. If only Thornton had designed the Octagon, he could have gloried in that and laid his rivalry with Tayloe to rest.

|

| 162. Sir Archy and the Rattler broadside |

Thornton won on appeal. In 1827, the supreme court ruled that the lower court judge erred in instructing the jury not to consider the condition of the horse. The decision was written by Justice Bushrod Washington, the nephew of George Washington who Thornton had befriended in 1799 when he fancied he was all but a member of the Great Man's family. What the lower courts did after that is unknown. Wynn died in 1827, and, in 1830, Thornton's wife acting as Thornton's executor settled with Wynn's estate out of court.(32)

Of course, that Driver came back lame and that the Thorntons never seemed to forgive Tayloe, doesn't prove that he didn't design the Octagon. But in 1802, with many and Thornton especially expecting a building boom, he became obsessed with beating Tayloe. The city needed housing not horses, architects not breeders. As an architect, Thornton played almost no role.

In 1801, he arranged for Secretary of State Madison to rent the house being built next door. He thought doing such a favor for President Jefferson's most influential advisor would help in his quest to be page 248 appointed Treasurer of the United States, which would

have almost doubled his salary.

He didn’t design the house, but he claimed he ordered alterations: "I have directed the third Story to be divided into four Rooms, two very good Bed-chambers, & the other two smaller Bed chambers. The Cellar I have directed to be divided, that one may serve for wine &c, the other for Coals &c—and for security against Fire a Cupola on the roof, which will add to the convenience of the House in other respects. There will be two Dormer Windows in front, & two behind."

| |||

| 163. Federal style townhouses with dormer windows on the 1300 block of F Street |

Beginning

January 1803 and ending in 1815, Mrs. Thornton kept a running account

of kitchen expenses and a few other transactions and briefly noted what

she and her husband did. Her 1803 notebook began with the Thorntons' New

Year's Day visit to the Tayloes. He

returned the visit on the 4th; Dr. T saw Tayloe on the 22nd; on the

26th they went to the Tayloe's for tea; on February 1, she went to

the Tayloe's with her mother; on the 19th they went to see Mrs.

Tayloe; Mr. Tayloe dined with them on the 20th; Dr. T dined with

Tayloe on the 23rd; on March 1 they went to an evening party at the

Tayloe's; Mrs. Tayloe called on the 14th; she had tea with page 249 her on the

15th; he dined with Tayloe on the 24th. With congress out of session

and the social season over, the Tayloes left town.(34)

For thirteen years she noted when she or her husband went to see the Tayloes, but never noted that her husband designed the house. Not until May

8, 1808, did she note that her husband designed another: "Dr. T. working on a plan for Mr. Peter." From that, one can conclude Thornton's season of designing houses in 1800 did not prove that he always had an itch to design houses.(35)

Yet, because Thornton's design for Peter had oval rooms, it is added to the proof that he designed the Octagon and Law's house which also had oval rooms. They could just a well be taken as proof that, once again, he copied the ovals in the Octagon, just as did in February 1800 when he designed his own house for Square 171.

In his papers in the Library of

Congress there are at least five floor plans for the Peter family's Tudor

Place in Georgetown that are attributed to Thornton and dated 1805-1816. Thornton's plans

connect the original buildings with his characteristic ovals and

colonnade. The house as built has the oval under the columns at the temple-like door but does not have any oval rooms. There is nothing like the Treaty room in Tudor Place. Thornton

is that rare architect who became famous even though what he designed

was rarely built as he designed it. The colonnaded entrance to Tudor

Place is the glowing exception.

| |||

| 164. Thornton's Tudor Place floor plan; actual floor plan below |

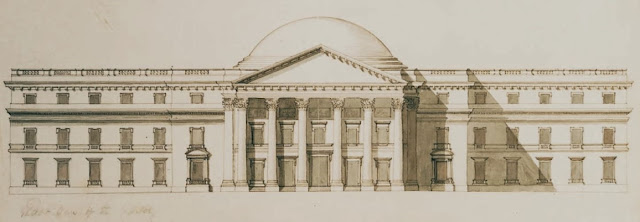

The next chapter discusses Thornton's feud with Benjamin Latrobe, a master of Neo-classical designs. In April 1808, that feud reached its climax. Perhaps that inspired Thornton to draw designs for Peter to rival anything Latrobe could do. With its 32 windows facing the street the Octagon is quite Georgian. Thornton's elevation for Tudor Place shows his long fascination with Roman temples.

|

| 165. Thornton's Tudor Place elevation |

Not until three years after she briefly noted that her husband drew a plan for Peter, did Mrs. Thornton note that he drew another house plan: "Dr. T drawing a plan of a house." She said no more. The day before, she noted that "Mr. Lovering called and left a book."35A

As will be shown, in 1811 Thornton was fighting for his right to profit from the development of steamboats, was the defendant in a libel suit over the design of the Capitol, also a Captain in the horse militia, and proud owner of Eclipse Herod who he was sure would soon dominate the turf. His official job was superintendent of the Patent Office. That, and his other activities did not preclude him from designing a house. But it bears noting that nothing else is known about the house plan he drew in May 1811. Thornton's fame as an architect is based on his design of the Capitol. Some hundred years later, Glenn Brown found it convenient for his own career advancement to embellish Thornton's fame by crediting him for designing the Octagon. Contemporaries found in Thornton a notable and never dull personality, but, he did not entertain them with a trajectory as an architect. In his history of American art and design, William Dunlap quoted an estimation of Thornton that listed only one architectural achievement, the Capitol. No matter that nothing else notable in that line followed. All else about him was sterling: "He was 'a man infinite humour,'- humane and generous, yet fond of field sports - his company was a complete antidote to dullness."35B

At that time, Lovering was listed in the Baltimore directory as an architect, which was what he had been since he landed in Philadelphia in 1793. But when he again crossed paths with Thornton in 1811, Lovering had no public personality and his trajectory as architect was known to few. Thanks to Greenleaf, Morris and Nicholson, he had not had an easy life and even his successes did not make him famous.

He did not keep construction of the Octagon within its contracted price of $13,000. In a June 14, 1801, letter to Lovering, Tayloe fumed "my Object is to be

done with the building as quickly as I can with the least trouble and

vexation - for the expense of it already alarms me to death when I

think of it."(36) page 250 Tayloe's

ire and the long time he took to build the house might explain why Lovering's

May 1800 newspaper advertisement offering specimens of houses for lots with obtuse and acute angles did not

attract any takers, except Thornton. It is also might explain why Tayloe is not known

to have ever said a good word about Lovering. Stier also became vexed at Lovering because of delays in building his house. In a letter to his son, Stier called Lovering a "blockhead."1

That said, while working on the Octagon, Lovering prospered. In 1799, he married Mrs. Susan White, a Georgetown widow. He formed a partnership

with the brickmaker William Lovell. They advertised for slaves, men

and boys, to make bricks.

Lovell supplied bricks for the Octagon but he also began building two

brick houses near the President's square likely with Lovering

designing and superintending them. In 1802, the Union Tavern and

Washington Hotel opened and ads boasted that it had a "coffee room 34

feet by 22, and a room over same, now finishing." In 1794, one of the

houses Lovering built for James Greenleaf was amenable to conversion to a

hotel. One of the oval rooms page 251 he built for Thomas Law was 32 feet long.(37)

|

| 167. Lovell's Hotel |

His supervision of construction of the Upper Marlboro Courthouse likely continued into 1801. Lovering also supervised work at the Capitol. The House of Representatives decided being upstairs in the North Wing wouldn't do. To better accommodate its 106 members, the commissioners ordered a temporary meeting place built on the site of the South Wing. Once again the board needed the services of an architect and once again Thornton didn't mind Hoban making the design, with the caveats that it be elliptical in shape, use the foundation already laid and incorporate features that could be used when the permanent South Wing was built.

All did not go well. On January 17, 1802, Commissioners Thornton and Alexander White wrote a letter to Lovering chiding him for being “so inattentive to the work places under your superintendence at the Capitol that Mr. Clagget and all his hands [likely his slaves] have quited the building.” Delays and cost overruns did not bode well for Lovering's future reputation. (39)(40)

The

new Seventh Congress convened on December 7, 1801, in what Thornton

called "the elliptical room" and members soon called the "oven." It was

that stuffy. More menacing were unstable walls that had to be buttressed on

the outside. Thornton's orders didn't work out. In 1803, in his report

on the condition of Capitol, written before his feud with Thornton

began, Latrobe noted that the temporary building seemed to be "intended

for the permanent basement of the elliptical colonnade" Latrobe found

that foundation poorly laid and "wholly unfit to carry the weight of the

colonnade."(41)

The last known letter that Lovering wrote was to President Jefferson. At the request of President Adams' servant, Lovering had made a contraption for drying linens but didn't finish it before Adams left office. Lovering was left holding the bill from the blacksmith who made the"mangle." On June 16, 1802, he mentioned the bill in a letter to Jefferson and offered to show his servants how to use the apparatus. Jefferson's secretary replied that there was no need nor money for it.(42)

|

| 169. Lovering's mangle |

By the summer of 1804, Lovering left Georgetown and crossed the Potomac to Alexandria, then a part of the District of Columbia. Beginning in May 1804, he advertised himself as an "ARCHITECT and Builder in general from the City of Washington and Georgetown." He shared his new address "where he Draws, Designs, and makes estimates of all manner of Buildings and also MEASURES AND VALUES all the different work connected to the building art." He was ready to "contract for any building and complete the same, from a palace to a cottage, which will be executed in the most masterly and economic style." He claimed he had "long experience" but didn't list any houses he designed or built.

In his ads offering his horses as studs, Thornton did not have to describe what a stallion did so he celebrated the horses' pedigree. In his ad, Lovering had to note the various things an architect could do and the variety of structures he could design and build. That the General himself avoided using an architect to build two houses suggests that an architect had some explaining to do to get work. Then again, if Lovering mentioned working for Tayloe and Law, readers would conclude that they likely couldn't afford him.(43)

By 1809, Lovering was in Philadelphia offering lessons in architecture and carpentry. He was likely around sixty years old, and had just four more years to live. In 1810, he was listed in the Baltimore City Directory as an architect. In 1811, in Baltimore, he did a favor for Thornton, and likely died in that city in 1813.(44) As an epitaph, it can be said that he built too many houses which diminished his reputation as an architect in the 20th century.

To be sure, he had no reputation in the mid-19th century either, which probably contributed to one of Tayloe's sons writing to his son in 1870, compounding the mistaken page 252 recollection that “The Octagon was built by your grand father in the administration of President Washington who took much interest and frequently walked to examine the progress" with a mistake attribution: "Dr. William Thornton drew the plan.” When William Henry Tayloe wrote that, his father and Thornton had been dead for 42 years, and he had not lived in the house for 40 years. Since his mother's death in 1855, no member of the Tayloe family had occupied the house.(45)

Benjamin Ogle Tayloe, the son who centered his career in the city more than his brothers, had a house built on Lafayette Park where he added wit to the Tayloe tradition of gracious entertainment. He had many stories about Thornton, none about his designing any houses. One story based on rumors generated by keepers of Thornton's papers after Mrs. Thornton’s death kindled another legend about Thornton that explained the mysterious Mrs. Brodeau. She was the secret wife of the notorious Dr. Dodd who had been hanged in London for forging a bank note: "His widow wonderfully kept the secret, and on her arrival in Philadelphia opened a boarding school for young ladies which was patronized by the best families in the city. Here Dr. Thornton fell in love with her daughter, and married her, after being informed by her mother of her real name and parentage."(46)

|

| 170. Mrs. Thornton's father? |

In her papers at the Library of Congress, there is not a hint that Mrs. Thornton knew of her supposed connection to Dodd. Yet, the story continues to be repeated. Rumor often has more agency in history than fact. That Mrs. Brodeau came to Philadelphia with money, a young child, and without a husband required an explanation. That a popular divine who before facing justice spent time in Paris, where such things are common, was proof enough that little Anna Maria Brodeau was his love child. That he forged bank notes because he needed money did not necessarily disprove that he gave Mrs. Brodeau a comfortable sum.

Thornton also had a propensity to make things up as his feuds with Benjamin Latrobe and Robert Fulton demonstrated.

1. Mrs. Thornton's Diary pp 107, 108, 112. National Intelligencer, 5 January 1801, "Conrad and McMunn" ad, p. 4

2. Ibid. p. 115, 175; Harris, p. 582

3. Ibid. p. 116. National Intelligencer, 5 January 1801, p. 4, "For Sale" ad

4. Ibid., pp. 121, 182

5. Scott, Creating Capitol Hill, p. 116;

6. Mrs. J. Q. Adams to John Adams, 22 November1820; A. Adams to Cranch, 4 February 1800 footnote 3; Law to Greenleaf, 9 April 1800: Cranch to A. Adams, 24 April 1800; see also Abigail Adams to Anna Greenleaf Cranch, 17 April 1800.

7. Mrs. Thornton's diary, pp. 107, 141.

8.Ridout, Building the Octagon pp.61, 80

9. Op. Cit., pp. 124-5

10. Ibid., p. 107

11. Ibid., pp. 116-7; Cohen pp. 117-8, already cited in Chapter Ten

12. Ibid. p. 122.

13. Ibid. pp 151-3

14. Ibid. pp. 156-7; Pettigrew 2: 546-7.

15. Wolcott, Oliver, Administration of John Adams, p. 378.

16. Diary, p. 209

17. Ibid, p. 217

18. Ibid., pp. 157, 182, 187, 197

19. National Intelligencer 5 April 1802 p. 3

20. Ridout, p. 92

21. Cutler, Manasseh, Life, Journals and Correspondence, vol. 2, p 142-143 (Google Books)

22. AMT papers, volume 3, end with image 147

23. National Intelligencer March 21, 1804, p. 4.; WT to Madison, 19 Nov. 1804 for how Madison utilized Clifden's services

24. Clark, "The Mayoralty of Robert Brent." CHS ol 33/34 pp. 283, 288-290; American Turf Register ; King, Julia, Hadfield p.

25. Tayloe, In Memoriam, p. 245; Mrs. Thornton's on-line LOC vol. 3 1807-1815, October 3, 1811.

26. American Turf Register, vol. 4 p. 391-2.

27. AMT vol. 3

28. Rattler Broadside

29. Thornton v. Wynn 25 US 183 ; Amer. Turf Reg, vol. 1, April 1830, p. 381

30. Tayloe, In Memoriam, p. 100

31. Rattler Broadside

32. Thornton v. Wynn 25 US 183 ; Thornton v. The Bank of Washington

33. WT to Madison 16 March 1801; WT to Madison 15 August 1801; WT to Madison 8 September 1801; Harris p. 581

34. AMT Papers vol. 1 image 129ff

35. Ibid., vol 3 images

35. Dunlap, William, History of the Rise and Progress of.... p. 336

36. John Tayloe letterbook, quote in Kamoie dissertation p. 200 footnote. Records of Assessor's Office "Assessment of improved property in 1803."

37. Natl. Intelligencer January 23, 1800. Ridout , p. 137 n. 20; Commissioners proceedings, May 15, 1800; National Intelligencer ad date 26 November 1802

39. Callcott, p. 29

40. Commrs. Records; Claggett and his slaves who he insisted should be paid the wages of skilled workers also worked at the Octagon. Tayloe refused and Claggett won a court case against him. On the hazardous state of the chamber see Jefferson to Claxton 26 October 1802

41. Latrobe to ******------ p.279

42. Lovering to Jefferson, 16 June 1802,

43. Alexandria Daily Advertiser, vol. 4, no. 1060, page 4, 11 August 1804

44. Balt. City Dir. 1810, p. 117; AMT notebook vol. 3 image 124; Brereton-Goodwin, Faye, "Thomas Brereton of Dublin, Ireland, Pennsylvania USA"p. 23: Lovering's third wife moved in with her step-daughter's family after William Lovering died. Amelia Lovering married Capt. John Brereton, USN, in 1814..

45. Harris, p. 584; Ridout, Building the Octagon p. 107

46. Tayloe, Benjamin Ogle, In Memoriam, Benjamin Ogle Tayloe, pp. 99, 100

Comments

Post a Comment