Chapter Sixteen: A "Blockhead" and a "Fool" - Latrobe challenges the ideas of Thornton

Table of Contents page 253 pdf

Chapter Sixteen: A "Blockhead" and a "Fool" - Latrobe challenges the ideas of Thornton

|

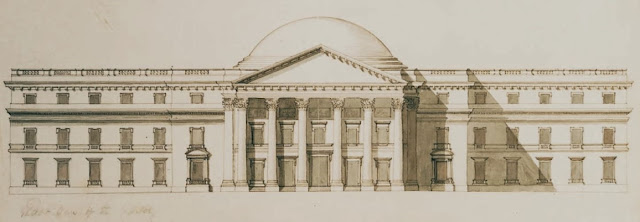

| 171. Detail from Birch's 1800 watercolor of North Wing. The building itself took only one third of the canvas. Did a lack of ornaments make a distant view more congenial than a closer look? |

On February 5, 1800, Mrs. Thornton reported: "Dr. T at work all day on the East Elevation of the Capitol. - I assisted a little till evening -." Again on February 7, "Dr. T was engaged in working at his plan of the Capitol." And again on February 9, he was "engaged on his plan of the Capitol." On February 14 "In the afternoon and evening drew on his plan of the Capitol." On October 11 "Dr. T had the head ache in the morning drawing at his plan of the Capitol." On December 19 "I began to copy the ground plan." On December 20 "did all I could with Dr T's directions to the plan of the Capitol."(1)

If he had informed his colleagues in

September 1798 that he had restored the design, why was he still

working on it in 1800? Mrs. Thornton's offered no explanation. At the same time, he was not open to suggestions from others that might require changing the design.

In

late April 1800, Vice President Jefferson wrote to Thornton sharing ideas about the Senate chamber, especially the position of

the seat for the presiding officer, i.e. the vice president. He

wanted the presiding officer's chair to be placed so people could

walk behind it and not be forced to walk between the chair and where

senators sat. He thought it "may be done ornamentally even, by

making an alcove etc. for the chair, behind which may be the

passage." He also wanted a balustrade in the back of the senate

placed so that only a single person could walk back and forth. More

walkers caused a "great disturbance." Then he suggested

having two balustrades page 254 crossed "to form a bar at the door in a

kind of pew by itself." He noted that the House of Commons has a

Speaker's chamber "which is a great convenience. Even a closet

will do as a substitute." Then he discussed where that could be

placed to advantage.(2)

One would think Thornton would jump at the opportunity to go back and forth with the man he hoped would be the next president. The day he got the letter, April 26, he began working on his design for Bishop Carroll's church. That gave him another reason to discuss the accommodation of people gathered in a room.

However, in his May 7 reply, Thornton assured the vice president that what he had suggested was "so nearly consonant to my plans that what I had directed will I flatter my self will meet with your approbation."

In the rest of the long letter to Jefferson, he suggested ways to end yellow fever epidemics. Lye in privies and ash spread in reservoirs were at the top of his list. Jefferson was also President of the American Philosophical and thus a butt of such speculation. Actually, a campaign to clean privies began after Philadelphia's 1798 epidemic.(3)

Everyone expected congress to abolish the board. Thornton should have realized that Jefferson, an amateur architect himself, had his own ideas about the Capitol. To retain any power, Thornton needed to build a relationship with, and not lecture him.

According to Mrs. Thornton's diary, Thornton had actually not finished giving his directions vis-a-vis the Senate chamber. On May 24, "Dr. T came in about one o'clock with Mr. Claxton doorkeeper to the Congress, who is empowered to procure the necessary furniture for the Capitol - they sent for Mr. Hoban and were consulting respecting the seat of the President of the Senate."(4)

While congress appropriated $50,000 to get the city ready to receive the government. It gave the money not to the commissioners but to the four cabinet officers. The cabinet put Stoddert in charge of that fund and Stoddert sent Thomas Claxton to the federal city. The commissioner gave him a house by the Capitol. It was too small for his large family. He demanded a larger house being vacated by stone workers, and wanted his assistants to move into the house he was vacating.

On February 10, Thornton had given Hoban a sketch for the capitals on the columns inside the Senate chamber. After that. Claxton, not Thornton, was the man giving orders. This was not a tectonic shift. In April 1799, Thornton had told his colleagues that he would gladly offer advice but it was up to Hoban to get the North Wing ready for congress.(5)

While Hoban and Claxton were busy at the Capitol, Thornton decided to improve the President's house. In January, Stoddert had privately commanded Thornton to make the President's house suitable for a gentleman and his family. Thornton found a contractor with exquisite taste to provide wall paper, and a plasterer in Baltimore who could also make stucco ornaments. Without soliciting anybody's advice, Thornton suggested the designs.(6).

On November 1, the chariot and four with the President Adams and his secretary rattled by Thornton's house on its way to the President's house. Exactly how the president expressed his displeasure is not known. But that day, the board sent a note to the plasterer to "take down figures at the president's house intended to represent man or beast" and replace them with plaster urns. Thinking ahead, Thornton took the decorator under his wing and tried to show samples of his ornaments to Jefferson. As Mrs. Thornton explained in her diary: "Mr. Andrews came with Dr. T. and brought some samples of his composition ornaments. Dr. T. wanted to show page 255 Mr. Jefferson." But Jefferson did not drop in as he promised. Thornton saw him a few days later but Mrs. Thornton did not know or note what transpired.(7)

|

| 172. Thornton by his friend Gilbert Stuart, 1804 |

Once congressmen came to town, Thornton didn't seem to have sense of what was going on. The day the news came from South Carolina guaranteeing Jefferson's election, Thornton traipsed off to a slave auction, but it was postponed. For six years, he had been a courtier smug in his office but over 100 miles from the court. In December 1800, he had to become a lobbyist and influence men he didn't know and about whom he had rarely thought.(8)

Blodget came to town, stayed with the Thorntons, and seemed to give some direction. The letter Thornton had written to him in February about the massy rock tomb for the General and his wife was printed in the National Intelligencer. An anonymous "extract of a letter from the city of Washington" made its way from New York City into a Norwich, Connecticut, newspaper: "The Capitol I believe to be the most elegant building in the world, and does great credit to Mr. Thornton's taste." Then the rest of the long paragraph extolled Blodget's hotel as the perfect place to house the Bank of the United State, which may have diluted the impact of the extract.(9)

Commissioner

Scott died on Christmas Day 1800. On the next day Thornton went to Virginia for the funeral. Blodget stayed back with Mrs. Brodeau and Mrs. Thornton. The latter noted in her diary that "Mr. Blodget making a sketch of Dr. T's

plan for our University on Peter's Hill." But the General was not alive to see the project through.(10)

page 256 With Scott's death, Thornton became the senior member of the board. President Adams immediately appointed his nephew William Cranch, which Thornton applauded. A New England congressman had prompted a move to investigate the conduct of the board. The Massachusetts born, Harvard graduate was just man to make the briefs justifying the board's conduct. However, Cranch only lasted a month. His uncle gave him a lifetime appointment as a federal judge in the District of Columbia. Adams put his old Massachusetts friend former senator Tristram Dalton on the board. After taking office on March 4, President Jefferson didn't change the board, even though Dalton had opposed his election.

Given Commissioner White's propensity to stay with his wife in Virginia and Dalton's inexperience, Thornton thought he was in control. However, with congress in the city everyone paid less attention, if any, to the board. For example, the owner of Rhodes Tavern, whose establishment was near the commissioners' office, built a wooden building too close to his brick tavern which broke a rule. The board ordered it removed, President Jefferson, who lived on the other side of Rhodes Tavern, agreed but the owner did nothing.(11)

Then the president seemed to lose patience with the board. In the late summer of 1801, he ran the government from Monticello. Being further away seemed to shorten his fuse. A long and rambling letter from the commissioners on the perplexities of paying interest on the Maryland loan prompted Jefferson to ask that the board decide an issue among themselves and simply ask him whether he approved or disapproved.(12)

Meanwhile, congress, especially the House, had to cope with all the discomforts and inadequacies of the Capitol. Who else to blame but the commissioners? In April 1802, the congress abolished the board and "thereafter all powers invested in the said Board ought to be vested in and discharged by an agent appointed by and to be under the control of the President of the United States."(13) Thornton seemed to think that the board's demise was analogous to Washington's retirement in 1797 and thus a time once again to make policy decisions to assure creation of the grand capital envisioned by its namesake.

In his first message to congress, Jefferson pledged to pay off the national debt and end wasteful government spending. He also warned the board to economize. But in an April 17, 1802 letter to him, Thornton dusted off his plans for Water Street, wharves and water lots. Thornton assured Jefferson that no money need be spent, yet. What was needed was only a presidential decision. However, Jefferson didn't want the federal government to build the city. He would try to limit its expenditures by only finishing the Capitol, President's house and the grand avenue between them.(14)

The

president didn't react to Thornton's letter, nor did he appoint

Thornton to carry on the work of the board.

Hoping for that appointment may have been Thornton's motive for

writing the letter about Water Street. His hope of becoming the Treasurer of the United

State had been dashed in November 1801 when Jefferson appointed the brother of a

close Virginia friend.

The board's reign ended on June 1, 1802. In a last letter to the president, the three commissioners notified him that they put everything in their office in the care of their "clerk." A few days later, Jefferson appointed that clerk, Thomas Munroe, as Superintendent of the Public Buildings. Munroe was considered a gentleman. He and his family socialized with the Thorntons. He even endorsed some of Thornton's notes that remained unpaid in the bank. No matter, Mrs. Thornton complained to the president who assured her that the office was temporary. Munroe served into page 257 the Monroe administration.(15)

Then, a few weeks later, without any fanfare, Madison hired Thornton to be the State department's patent clerk. He didn't officially get the title Superintendent of Patents until 1821. In 1801, congress had delegated its Constitutional mandate to protect intellectual property to that department. All an applicant had to do was swear that his invention was original, that he had been an American citizen for two years and pay $30. It was not up to the patent clerk to determine if the invention worked or was original. But the clerk kept a register of patents which required a modicum of copying.

There is evidence that Thornton relished the appointment. On June 21, 1802, Thornton drafted another letter to his old master Dr. Fell. In the letter he wrote to Fell in October 1797 which recounted his life in America, he did not mention his work on the steamboat. He began his 1802 letter with the steamboat: "I engaged in constructing a steamboat capable of carrying 150 passengers and made it go eight miles an hour through dead water...."

In his 1914 monograph "Doctor and Mrs. Thornton," Allen Clark described Thornton's association with the steamboat in an artful way: "In the credit for the invention, it may be detected that the Doctor at first said he; further on we; finally I." Judging from his 1798 letter to Navy secretary Stoddert, his appointment as patent clerk was the catalyst for his jump from we to I. In that letter aimed at bolstering the armory of the navy, he claimed he had "invented" the steam-cannon. He also recommended not steamboats per se, but steam engines in every navy vessel to propel the boat during calm winds. He boasted that "we propelled a boat at the rate of eight miles an hour...." He didn't mention 150 passengers and referred Stoddert to Voight for "every information relative to construction" of a steam engine.

In his letter to Fell, he didn't mention Fitch and blamed the company's failure on his orders not being obeyed. As he left for Tortola, he had told the company's board members not to make any changes in the boat. As he put it to Fell, he had to work against "wind, tide and ignorance." He overcame the first two but "the last is an overwhelming flood." The draft of the letter ends without his mentioning his recent appointment.

There was a downside to his appointment. In his first full year on the job, the state department issued around 40 patents. That meager output only justified a low salary, $1400. However, as he moved into his new office, his contributions to the development of the steamboat was on his mind. Fitch had killed himself in 1798, and bequeathed most of his worthless estate to Thornton. His patent would expire in 1805. Despite continued talk, nobody had a working steamboat that rivaled Fitch’s. When anyone did, they would have to reckon with the patent office.(16)

To celebrate becoming a member of the Jefferson administration, Thornton, his wife and mother-in-law rode to Montpelier and then Monticello to rusticate with his boss and the president. The president did him another favor by making him one of the District's Commissioners on Bankruptcy. The president calculated that thanks to fees arising from processing bankruptcies as well as his magistrate's fees and his patent office salary, Thornton would make $2000 a year. However, Thornton later claimed that he only took $150 in bankruptcy fees because he did not want to add to the burdens of bankrupts.(17)

His southern jaunt was also profitable in a way Thornton could not have imagined. While with the Madisons, he made a drawing of Montpelier. Based on that, in 1896, Glenn Brown would claim that Thornton designed the house.(18)

|

| 173. Montpelier |

During the visit to Monticello, Thornton and the president evidently didn’t discuss the Capitol. However, when they were back in the capital, the president invited Thornton, as well as Benjamin Latrobe, to one of his famous dinners of ten people. The president had summoned Latrobe to build dry docks just north of the Navy Yard. Jefferson wanted to limit the expense of navy by putting its ship on land.

The two architects had met in April 1798. Latrobe was then on his way to and from Richmond where he designed a prison and Philadelphia where he page 258 designed a bank. He had gained some idea of the Capitol design in Philadelphia when he saw Volney's copy of it as well as a floor plan made by Hallet that James Greenleaf showed him. In the page of his journal before he described his visit with Thornton, Latrobe wrote a long critique of the house L'Enfant designed and almost finished in Philadelphia for Robert Morris. Having been told in Virginia that it was the greatest house ever built, Latrobe ridiculed what he saw as faux chateau monstrosity with a mansard roof.

|

| 174. "Morris's Folly" |

L'Enfant's folly likely primed Latrobe to appreciate the Neo-classical simplicity of Thornton's elevation. In his diary entry just after his ridiculing L'Enfant, he confided that Thornton's design "though... faulty in external details, is one of the first designs of modern times." He added that he offered "to give to the doctor a drawing in perspective of his design which I trusted would convince him of his errors." Thornton would remember only the compliment.(20)

The dinner at the President’s house was in November before congress met. Once the social season began, the two architects met again. In his memoirs, Latrobe recalled how Thornton boasted of his massy rock tomb at a social gathering. Latrobe had offered a massive pyramid as a mausoleum.

|

| 175. Latrobe's design for Mausoleum |

Thornton explained to the gathering that Latrobe was the sort of man who didn't understand allegory which was so important in art. For example, Latrobe could never conceive of Thornton's monument to Washington which had the female figure of eternity, indicated by a snake circled around her neck, beckoning Washington to the peak of a mountain.

Latrobe retorted that when the ruins of the Capitol were uncovered, the lady with the snake around her neck would be interpreted as a poisonous woman seducing a man to forsake his family as represented by the figures of a woman and children below who Thornton said represented the arts and sciences. Latrobe recalled "I was going on but the laughter of the company and the impatience of the doctor stopped my mouth. I had said enough and was not easily forgiven."(21)

| ||

| 176. Benjamin Latrobe by Charles Wilson Peale |

Congress tabled the dry docks which freed up Latrobe for other projects. In 1803, Jefferson put Latrobe in charge of finishing the Capitol. One drawback to hiring Latrobe was that he continued overseeing work in Philadelphia and Newcastle, Delaware. In 1802, he became page 259 chief surveyor for the Chesapeake and Delaware canal. He was often out of town. The great advantage to hiring him was that he shared many drawings with the president.(22)

Meanwhile, Thornton appeared to be engrossed in other arguably more important matters. His office was in the same building as

the secretary of state's, one of the town houses that

formed what was known as the Six Buildings on Pennsylvania Avenue

just northwest of the President's house. Thornton thought that since

he had little patent work to do, he had time to advise Madison on

foreign policy matters. However, his letter to Madison about Napoleon crossed Madison's letter to him about carriage horses.(23)

Thornton also had time to become a public intellectual. He began thinking of a proposal to send America's free blacks to Puerto Rico which would require some sharp diplomacy to distract the then powers of the world, Britain, France and Spain.(24)

Then the city was consumed with the purchase of the Louisiana Territory for $15 million which almost doubled the size of the country and increased the national debt by 19%. It also inspired Thornton to find another place for freed slaves. His 24 page essay, "Political Economy: Founded in Justice and Humanity, in a letter to a friend," advised congress go in debt to buy slaves from American masters, put them to work on building roads and canals, and eventually send those who proved worthy to the farther reaches of the newly acquired Louisiana Territory.

In the essay, he identified himself as a slave owner in Tortola and regretted that inheritance. He noted that his slaves rapturously greeted him when he returned to the island and later wept at his mother’s death. He didn’t allude to his step-father owning half the slaves nor did he mention his 1786 resolve to free them and satisfy his mother’s condition for their liberation by taking them to Africa. Instead he noted his objection to a new law in the islands that required anyone who freed a slave to provided 10 Pounds annually to the slave. Thornton said he argued that such a provision made sense only for young and old slaves. That money would discourage able bodied slaves from working.

page 260 The “friend” to whom Thornton addressed his letter was an anonymous legislator who sounded much like James Madison even though in 1804 he was in the cabinet. Thornton’s point seemed to be that emancipation had to be effected by fool proof legislation. He even faulted how George Washington willed freedom for his slaves. That partial good act added to the “general evil.” Thornton did not allude to his personal experience with slavery in America. He didn’t mention hired slaves working on the Capitol, or slave jockeys or his servants. According to his wife’s 1800 diary, he accused two “hired Negroes” of stealing 12 of the best head of cabbages at the farm. But in his essay, he speculated that slaves resent seeing free blacks make money and thus steal from their masters. He deduced from the 1790 and 1800 censuses that the proportion of blacks to whites would increase and ultimately “the enslaved, being uneducated, would involve in promiscuous ruin the good and bad, and sacrifice, with unsparing hands the whole race of their enslavers.”

|

| 177. Snip of Thornton's book on slavery |

He insisted that by using the virtually unlimited public lands to borrow money to buy all the country’s slaves would be a debt that all of posterity would gladly pay since they would be forever grateful that the civilized part of the country was rid of blacks. He no longer thought Indians would massacre blacks and was confident that after the requisite years working on public improvements blacks would be “free, industrious, ingenious, virtuous…” and quite impress the Indians.

Latrobe, for one, thanked Thornton for his idea. His complement may have been a vain attempt to get Thornton to make it his hobby-horse instead of the Capitol.(25) Once appointed to his new job, Latrobe asked Thornton for a copy of his Capitol floor plan. The president gave him another copy. After Latrobe made changes to make the North Wing more convenient, he began building the South Wing. In a memoir written years later, Latrobe recalled his first reaction to the two plans given to him: "They were copies of each other and both perfectly useless; neither of them agreed with the work as founded or carried up, and there were no details whatever. In the superintendent's office no drawings existed."

page 261 He gave the plans "several days of severe study, and then stated to the President that I could not undertake its execution." In a letter written at the time, Latrobe wrote that the president said the plan could not be changed but promised to talk to Thornton about, as Latrobe put it, "objectionable parts of his plan." After seeing the president, Latrobe got the bright idea to go to Thornton first "to prepare the way for amicable adjustments."

In a short letter to the president, Latrobe reported what happened when he met Thornton at his office: "I judged very ill in going to Thornton. In a few preemptory words, he, in fact, told me, that no difficulties existed in his plan, but such as those that were made by those too ignorant to remove them and though these were not exactly his words, his expressions, his tone, his manner, and his absolute refusal to devote a few minutes to discuss the subject spoke his meaning more strongly and offensively than I have expressed it...."(26)

On February 28, 1804, Latrobe sent a report on the state of the Capitol to a House Committee and complained that he had no detailed drawings of the design. "The most indisputable evidence was brought before me to prove that no sections or detailed drawings of the building existed excepting those that were made from time to time by Messrs. Hallet and Hadfield for their own use in the direction of the work." (27)

Thornton sent a letter to Latrobe couched in terms that generally served as a prologue to a duel: "I am sorry to be obliged to declare that your Letter to the Committee is, as it respects me, not only ungentlemanly but false." When Latrobe accused him of wanting to take their dispute "to the field," Thornton said he didn't, but admitted that he had been prepared to settle an affair with another gentleman several months earlier.(28)

Latrobe sought a second or sorts. He wrote to Hadfield, who remained in the city, and had meanwhile designed and built the city jail and the Custis mansion in Arlington facing the President's house from across the Potomac River.

|

| 178. Custis Mansion in 1853 |

If Hadfield replied it has not been found. He never claimed what Latrobe attributed to him. In an 1801 letter to President page 262 Jefferson, Hadfield would recall "the painful mortification... of seeing my work remain for the praise and reputation of those, who have meditated and effected my ruin." Hadfield had also been prepared to press his case to the president. He assured him "I shall be able to substantiate my assertions, supported by some of the most respectable characters in this City." But in 1804, he had nothing to gain by getting into a public dispute with Thornton.(29)

When Latrobe brought his plans for the South Wing to the president, he reminded him that the legislation authorizing resumption of work on the Capitol mentioned making plans. He naively thought he could do just that. He didn't know about the power of "the ideas of Dr. Thornton."

Their enduring commitment to those ideas is what saved Washington and Jefferson from seeming to be complete fools for being taking in by Thornton's contest winning design. Both presidents also had feared that if congress got the impression that the plan for the Capitol was not settled then congress would get involved and make its own plan. In a letter to his assistant John Lenthall, Latrobe vented his spleen: "when once erected the absurdity can never be recalled and the public explanation can only amount to this that one president was blockhead enough to adopt a plan, which another another was fool enough to retain, when he might have altered it."(30)

On January 1, 1805, Thornton published "A letter to "Members of the House of Representatives." It provided the evidence used by Glenn Brown, C. M. Harris and others to

prove that Thornton restored his design complete with drawings and sections at

the request of President Washington. Thornton even claimed that President Jefferson relied on him to make yet another drawing. "Some months before" Latrobe's appointment, the president asked how offices and committee rooms could be fitted in the basement under the House chamber. Thornton then drew a plan. Unmentioned in Thornton's letter was that the drawing was useless. The president gave it to Latrobe on January 15, 1805. Latrobe already had started work on that part of the building.

|

| 179. Latrobe's inscriptions on Thornton plan the president gave him |

Thornton made much of all that Latrobe had said to him about the design before he was appointed. He claimed that Latrobe said that "....he never saw any plan of a building beside his own that he would deign to build." Thornton added: "I must page 263 own that I can not easily conceive why previous to this appointment I should hear nothing but approbation of my plan and after his appointment nothing but condemnation."(31)

Thornton could not conceive of Latrobe's change of heart because he had never supervised the construction of his own or anyone else's design Meanwhile, without consulting Thornton, the president had let Latrobe make another design for the House chamber. Latrobe had the good sense to use some of the president's ideas.(32)

|

| 180. Floor plan Latrobe gave to Jefferson in 1806. Below is Thornton's floor plan |

Despite corresponding frequently with George Washington during the last 14 months of his life, Thornton was never able to get from Washington what Jefferson would give to Latrobe. Washington never thanked him for his contributions to the design of the Capitol. Fortunately for page 264 Thornton, Hadfield refused to

comment. However,

there was one man friendly with Thornton who had seen his prize winning

design as well as the changes made to it.

In 1806, Samuel Blodget published his 226 page opus Economica, the first American tome on economics. He leavened valuable statistics by arguing that the government should finance development by increasing the national debt as much as needed and securing it with Western lands. He also discussed the City of Washington. He lauded Thornton's Capitol design, warned that the dome must be built, and invited Thornton to assume a new role: "For this truly sublime and beautiful building, Dr. William Thornton received the premium; but as it has undergone some changes, by deviations agreeably to taste... of the several ingenious gentlemen who have superintended the work, we know not how much the architect will disown."

That sentence explodes any notion that as a commissioner Thornton had restored his original plan with which Blodget was familiar. As Blodget saw it, "several ingenious gentlemen" had made changes, and Thornton was only left with deciding what was good or bad in the building. That was a very reasonable approach and, if followed in the right spirit, would have gained Thornton credit for nourishing the growth of the building for which he helped plant the seed.(33) There is no evidence that Thornton reacted to what Blodget wrote.

Then in the late summers of 1805 and 1806, good fortune seemed to smile on Latrobe. The doctor found another distraction on which to employ his genius. Gold temporarily separated Thornton from the Capitol. He left Washington to buy land in North Carolina where gold had been found, and he took his wife and mother-in-law with him.

During his tour of Scotland with the geologist Faujas in 1784, Thornton had gained some experience assaying a land's mineral wealth. In 1804, the great Prussian scientist Humboldt had stayed with the Thorntons after his study of the earth's magnetism on Mount Chimborazo in Columbia. That likely recalled to Thornton how much he knew about geology.

After his 1805 trip, he organized the North

Carolina Gold Mine Company with a board of trustees to verify the land

deals he made in North Carolina. In the summer of 1806, Thornton panned for gold with

the locals. Because of the discovery of nuggets since 1799, land was not

cheap. Thornton decided he would have to raise $110,000 to buy enough

land, 35,000 acres, to assure every investor a fortune.(34)

But he didn't forget the Capitol. His touring the gold hills of North Carolina afforded him the opportunity of dropping in on both Madison and Jefferson when they were spending the summer at the their Virginia seats. On his second trip south, he tried to save the remaining part of his Capitol design. Latrobe had made the South Wing his own, but worked had not begun on the dome.

Just before Madison left for his home, Thornton put a letter on his desk that hailed President Washington for having personally banished Hallet in 1794 after he tried to change Thornton's design of the Capitol. According to Thornton, the president told him "to quit the place." That described something that had never happened which didn't prevent Thornton from applying that lesson to defeat a threat that didn't exist:

Mr. Latrobe, as if determined to oppose every thing previously intended has carried up a large block of building on the very foundation intended to be taken up, by which the Dome is so encroached on that the part already carried up on the north side will be useless. I am confident the President could never have permitted such a deviation from the original Intention if it had been made known to him. I page 265 think it my Duty to mention it now before it be too late to prevent its progress.(35)

|

| 181. Latrobe water color of what Capitol would look like that he gave to Jefferson in 1806 |

When Madison reached Montpelier on August 15, he sent Thornton's letter, "disclosing the perturbation excited in his mind, by some of the operations of Mr. la Trobe." Jefferson took Thornton's letter more seriously and replied to Madison: "If Dr. Thornton’s complaint of Latrobe’s having built inconsistently with his plan of the middle part of the capitol be correct, it is without my knolege, & against my instructions. For altho’ I consider that plan as incapable of execution, yet I determined that nothing should be done which would not leave the question of it’s execution free." That is to say, nothing should be done to preclude Thornton from thinking that his plan would be carried out even though both Jefferson and Latrobe knew the plan was "incapable of execution."(36)

There is no evidence that the president shared Thornton's concerns with Latrobe. Thornton did not give up, and looked to congress for help. By 1806, he had become more familiar with ways of congress and congressmen.

Latrobe

had to report to congress every year which afforded Thornton's allies

in congress an opportunity to snipe at him. In November 1806, Latrobe published a letter to

congressmen that addressed the root of the problem: Thornton's

insistence that only his original plan endorsed by George Washington

could be used. Latrobe lauded Thornton's achievement but debunked a

design contest as a good way to come up with a design and argued that

only someone who knew how a building could be built could design a

building.(37)

Then Thornton went too far. He gave up trying to impress the president. To make that clear, he attacked Latrobe and the South Wing in the Washington Federalist, the rival paper to the Jeffersonian National Intelligencer. In his April 2, 1808, attack, Thornton described page 266 Latrobe as a "carver of chimney pieces in London" who came to America a "missionary of the Moravians." He insisted that every change Latrobe made went against the wishes of General Washington. Thornton suggested that Latrobe "may have an antipathy to the name of Washington, for that great man was asked by a very respectable gentleman now living, why he did not employ Mr. Latrobe: 'because I can place no confidence in him whatever-' was the answer."

Thornton also ridiculed every decoration in the South wing: an eagle looked like an Egyptian ibis, Liberty on an eagle looked like Leda and the swan, country people mistook an eagle on the frieze of an entablature "for the skin of an owl, such as they have seen nailed on their barn doors." He ridiculed the problems of echos in the House chamber.

Thornton

attacked other buildings Latrobe had designed and his gate at the Navy

Yard. He also defended his own standing as an architect:

I

travelled in many parts of Europe, and saw several of the masterpieces

of the ancients. I have studied the works of the best masters, and my

long attention to drawing and painting would enable me to form some

judgment of the difference of proportions. An acquaintance with some of

the grandest of the ancient structures, a knowledge of the orders of

Architecture, and also of the genuine effects of proportion furnish the

requisites of the great outlines of composition. The minutiae are

attainable by a more attentive study of what is necessary to the

execution of such works, and the whole must be subservient to the

conveniences required. Architecture embraces many subordinate studies,

and it must be admitted is a profession which requires great talents,

great taste, great memory. I do not pretend to any thing great, but must

take the liberty of reminding Mr. Latrobe, that physicians study a

greater variety of sciences than gentlemen of any other profession . . .

. The Louvre in Paris was erected after the architectural designs of a

physician, Claude Perrault, whose plan was adopted in preference to the

designs of Bernini, though the latter was called from Italy by Louis the

14th.(38)

Recall that Thornton landed on continental Europe at the end of December 1783 at the earliest and returned to Britain by mid-August 1784. Rather than alluding to ancient buildings he had never seen, one would think that citing other buildings he had designed would be more telling. He attacked Latrobe's other designs but did not list his own. That is more proof that he hadn't designed any notable houses in the city.

By the way, Latrobe had noticed the Octagon. In 1804, to save money, a senator proposed putting congress in the President's house and the president into a private house. Latrobe opined that if the bill passed, only one other house in the city would do for the president, Tayloe's.(39)

Latrobe

sensed that Thornton's letter in the Federalist went too far. Latrobe

declared himself the winner. He wrote to a friend on May 28, 1808, that

Thornton "has miserably fallen in public estimation of late."(40)

Still, Latrobe sued Thornton for libel, but Latrobe later recalled that he told his lawyer not to ask for damages. Thornton's lawyer did his best to prevent a spectacle. The case dragged on until May 1813 when Latrobe won the case and one cent in damages. Tbornton turned the verdict to his advantage by telling everyone that Latrobe sued for $10,000 in damages and only got a penny.(41)

It is possible that Latrobe recalled not asking for damages to hide his embarrassment at page 267 only getting a penny. But in a letter he wrote in 1808, he blamed Thornton's being a "madman" because he was poor: "the worst that can be said of him is that he is a Madman from vanity, incorrect impecuniary conduct, and official intrigue from Poverty." Thornton performance in the Patent Office and his personal finances will be plumbed in the next chapter.(42)

Judging from Mrs. Thornton's notebook, the Thorntons continued their usual pace of entertaining despite his money troubles. His close friends likely thought he put Latrobe in his place. There were two important exceptions Madison and Jefferson.

Before it adjourned at the end of its short session in March 1809, just prior to Madison's Inauguration, congress appropriated $31,000 for continued work on the North and South Wings, and $12,000 for "continued improvements and repairs" of the President's house. Latrobe remained surveyor of the public buildings, and got to work. He gave the Senate a new chamber on the first floor, not in the basement.

|

| 182. Latrobe's Senate |

After the British burned the Capitol in 1814, Madison asked Latrobe to restore and finish the building. Latrobe sent Jefferson a detailed description of the damage to the Capitol, with drawings of what the heat did to the ancient orders. Thornton left nothing in writing that suggests that he evaluated the damage.(43)

|

| 183. Latrobe Drawing of Capitol Columns after the fire |

Latrobe

was soon facing headwinds. He begged Madison not to put him under three

commissioners. He blamed fights between commissioners and

architects for adding $250,000 to the cost of the original Capitol. Only

the good faith of workers saw the project through. A few months later

in another letter to Madison, Latrobe revealed difficulties placed in

his way:

On

the part of the Commissioners, I have been treated in a manner more

coarse & offensive than I have ever permitted, to myself, or felt

myself capable of using to my poorest mechanics. On the slightest

occasions I have been told that there were plenty of architects ready to

take my place, that I had been appointed from motives of charity to my

family, that, if I meant to continue in their service, I must obey their

orders implicitly, even when contrary to those given to me by the

Committee of the Senate;... I had been told indeed by one of them, that

my pride should be taken down before they had done with me... (44)

The other two commissioners were John Peter Van Ness, for whom Latrobe built and designed a mansion, and Richard Bland Lee, an elderly Alexandria FFV who had never been in Thornton's orbit. But Latrobe never implied that Thornton had anything to do with organizing opposition to his work through Ringgold. In this case, the worst that can be proved is that Thornton's unremitting criticism of Latrobe from 1804 to 1808 sanctioned others to continue attacking him.

When congress disbanded the three commissioners and put the restoration project under one man, Latrobe did not fare any better. President Madison appointed Col. Samuel Lane who soon delighted in pointing page 269 out criticisms that he claimed old hands like George Blagden and James Hoban had of Latrobe's ideas and work.(45)

President James Monroe soon lost confidence in Latrobe. During a shouting match in front of the president, Latrobe, who was over six feet tall, threatened Lane with bodily harm. The commissioner had a crippled arm. Latrobe resigned in November 1817.(46)

Latrobe's fall did not prompt anyone to ask Thornton's advice about who should supervise work at the Capitol. Charles Bulfinch who replaced Latrobe at the Capitol stayed clear of Thornton as best he could. After he met him while doing patent office business for a friend, Bulfinch described him in a letter as "a very singular character: the Dr. gave the original design for the building of the Capitol, and is very decided in finding fault with Latrobe for the changes he had introduced in it."

That said,

Thornton was not the root of all controversy at the Capitol. In one of

his first reports to congress, Bulfinch roundly criticized Latrobe's

building methods, specifically a stone arch in the North Wing. In 1808, Latrobe's assistant Lenthall was killed while removing a brick arch. Latrobe published a pamphlet vindicating his work.(47)

Then just at the time when it became very clear that Thornton's influence as an architect was nil, Jefferson enlisted Thornton's aid in filling a large quadrangle with buildings for the University of Virginia. Jefferson remembered Thornton's strengths and limitations. In a May 9, 1817, letter, Jefferson asked Thornton to "...set your imagination to work and sketch some designs for us, no matter how loosely with the pen, without the trouble of referring to scale or rule; for we want nothing but the outline of the architecture, as the internal must be arranged according to local convenience. A few sketches, such as need not take you a moment."(48)

Jefferson understood that Thornton was an outline of an architect. In his reply to Jefferson, Thornton was in his element: "I admire every thing that would tend to give chaste Ideas of elegance and grandeur. Accustomed to pure Architecture, the mind would relish in time no other, and therefore the more pure the better.—I have drawn a Pavilion for the Centre, with Corinthian Columns, and a Pediment. I would advise only the three orders: for I consider the Composite as only a mixture of the Corinthian and Ionic; and the Tuscan as only a very clumsy Doric."

Thornton's reply provides evidence enough for some biographers to credit Thornton for designing buildings on the campus of the University of Virginia. He at least influenced one design by drawing a pavilion that he enclosed in his letter to Jefferson.

|

| 184. Thornton's plan for Pavilion VII |

page 270 As C. M. Harris puts it Thornton "most noticeably influenced Jefferson in his design for Pavilion VII...."(49) In his letter, Jefferson described and sketched the basic arrangement of the campus with a one story colonnaded dormitories interspersed by two story pavilions "no two alike" for classrooms of the disparate schools with each illustrating a different style of Classical architecture. All the buildings faced a rectangular green. The challenge Thornton faced was choosing the order and arrangement of the columns and dimensions of the pediment. Thornton made wrong choices. The glory of Corinthian columns was lost in his design. If Thornton's sketch did influence him, Jefferson never discussed it with Thornton explaining why the pavilion with Doric columns had to be as he finally designed it and why that with Corinthian columns didn't resemble Thornton's sketch.

|

| 185. Pavilion VII |

At the same time that he wrote to Thornton, Jefferson wrote to Latrobe pressing him for ideas. Then between June and November 1817, he wrote six more letters about the university project to Latrobe. On January 9, 1821, Thornton wrote to Jefferson, "I have never been honoured with a line from you since your favor of the 9th of May 1817. which I answered on the 27th relative to the College about to be established in your Vicinity."

In his last letter to Latrobe, Jefferson lamented his being replaced: "I learned with great grief your abandonment of the Capitol. I had hoped that, under your direction, that noble building would have been restored and become a monument of rational taste & spirit. I fear much for it now. to [my]self personally it can be of little moment; because in the public page 271 bui[ld]ings which will be daily growing up in this growing countr[y] [you?] can have no competitor for employ."(50)

There is no evidence that Latrobe's downfall burnished Thornton's reputation. Until Glenn Brown discovered Thornton in the late 19th century, Latrobe was the defining architect of the federal city thanks to his Senate and and House chambers, St. John's church and Decatur House around Lafayette Park and the Van Ness Mansion below the White House. His untimely death in September 1820, from yellow fever while building water works in New Orleans to prevent yellow fever added to his reputation. That a son followed in his footstep as an engineer kept the name Latrobe in mind.

Some lost track of Thornton's connection to the Capitol even when he was alive. In 1818, a pictorial representation of the planned Capitol was finally published. A long time surveyor of the city, Robert King, produced a definitive map of the city showing all its 1170 squares. On the bottom corners of the map, he added engravings of the President's house and Capitol. The latter engraving was described as the "East Front of the Capitol of the United States as originally designed by William Thornton_ and adopted by General Washington_President of the United States." In the other bottom corner of the map was another small engraving: "South Front of the President's House as designed and executed by James Hoban."

In 1819, a competing image of the future Capitol appeared on the mast head of a newspaper called The Gazette with this explanation: "This vignette of the Capitol which we this day introduce into the Gazette was engraved by Dr. Alexander Anderson, of New York, from a design of Mr. George Hadfield, of the city, as originally approved of by George Washington." The mast head added "It may be proper to state, that since the restoration of the Capitol, an alteration (not included in our design) has been made by adding a cupola roof on each wing." The rotunda and dome had not yet been built.

|

| 186. Woodblock print of Hadfield's dome |

However, there is a degree of equivocation in this last piece of evidence. King's caption under the President's house simply says it was "designed" by Hoban.

|

| 187. Engraving of Hoban's South Front of President's House |

The caption under the Capitol says "as originally designed" by Thornton and "adopted" by the president.

|

| 188. Engraving of Thornton's East Front of Capitol |

That implies that Thornton's original design was changed in some respects through its being "adopted" by the president. That indeed is what, apart from Thornton's claims, the historical record shows. Also, in his statement about the etching on the 1818 map, Hadfield did not simply say it was Thornton's design. He said it was "acknowledged to be Dr. Thornton's design."

Hadfield seemed to adjust to his disappointment vis-a-vis the Capitol by adopting a pose of whimsical detachment. In 1819, fifteen years after being asked by Latrobe to reveal what he had designed in the North Wing as built, Hadfield modestly noted his contribution to the exterior of the building:

The

only parts that now remain, and which I, for the first time, claim as

emanating page 273 from my feeble architectural powers, in the exterior of the

North Wing of the Capitol, are the impost cornices to the basement

without the Galosh ornament, which was meant to top the basement,

without any moulding; the said impost was accepted as an improvement

and executed accordingly. Dr. Thornton is welcome to the credit of the

design, except the management of the dome with an attic which I claim as

my introduction in said drawing, believing it more consistent with good

architecture.

Thornton

evidently didn't react to the masthead etching or Hadfield's correction

even though Hadfield's public letter seethes with condescension in the

guise of abject humility.(51)

In 1822, in a letter to Hadfield's sister, Maria Cosway, who had been his dear friend in Paris, Jefferson credited her brother for being "much respected in Washington, and, since the death of Latrobe, our first Architect, I consider him as standing foremost in the correct principles of that art. I believe he is doing well, but would he push himself more, he would do better."(52)

|

| 188A. 1851 engraving of City Hall designed by Hadfield and built between 1820-1849 |

Thornton was lucky that Hadfield didn't push, and that aging former president never revealed what he really thought of Thornton. It was a different story with his old friend James Madison, the fourth president that Thornton served.

1. Mrs. Thornton's diary, pp. 103, 104, 106, 200, 223

2. Jefferson to WT 23 April 1800

3. WT to Jefferson 7 May ; AMT diary p 146

4. Ibid., p. 146

5. Ibid., p. 129; Annals of Congress, 6th congress, appendix, p. 1494; Arnebeck, Fiery Trial, p. 579;

6. Commrs to Stoddert 19 April 1800; Andrews**

7. Commrs to Andrews 1 November 1800; Diary pp. 208, 222

8. Diary, p 220

9. Ibid. p. 218; Norwich Courier 8 October 1800; National Intelligencer 8 December 1800.

10. Ibid., p. 225

11. WT to Jefferson, 31 December 1800 ; Commrs to Jefferson 6 January 1802,

12. Commrs to Jefferson. 17 August 1801, ; Jefferson to Commrs., 24 August, 1801,

13. Annals of Congress p. 1130

14. WT to Jefferson, 17 April 1802,

15. Commrs. to Jefferson 1 June 1802 ; Harris, p. lxxi

16. WT to Fell, 21 June 1802; Clark, "Dr. and Mrs. Thornton," p. 189; Chap, 7, footnote 8, The Pony Ride which cites , Natl. Archives, M234 roll 54 WT account 1/6/1803; Harris, pp. 573-4

17. in her notebook reel 1 image 123ff, Mrs. Thornton described their visits. Thornton deposition 1812 American State Papers vol p. 193

18. Brown, 1896, p. 63

19. For example, Thomas Tucker who Jefferson appointed Treasurer in 1801 served until he died in 1828. For dinner invitations see https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-37-02-0250

20. Latrobe to Mary Elizabeth Latrobe, 24 November 1802, Correspondence, p. 232; Latrobe to Jefferson, 27 March 1802; Jefferson to Latrobe, 2 November 1802; Latrobe to Jefferson, 9 November 1802 , 28 November 1802 ; Latrobe Journal p 189

22. Life of John Fitch, p. 382

23. WT to Madison 17 August 1803; Madison to WT 19 August 1803

24. Hunt, Galliard, "W. Thornton and Negro Colonization"

25. Thornton, "Political Economy: Founded in Justice and Humanity, in a letter to a friend" p. 6.; Latrobe to WT, 28 April 1804

26. Latrobe to Jefferson, 27 February 1804, Latrobe Journal, p. 190.

27. Latrobe Letters and Journal, p. 445

28. Ibid., Latrobe to WT, 28 April 1804 , p. 481

29. Ibid., Latrobe to Hadfield, 28 April 1804, p. 480; Hadfield to Jefferson, 27 March 1801; Latrobe to Jefferson, 28 February 1804, p. 441.

30. Ibid., Latrobe to Lenthall, 8 March 1804, letters p 450

31. Harris, p. 257; Brown, History of Capitol, new ed pp 113ff

32. for examples of Jefferson's involvement see, Jefferson to Latrobe, 16 January 1805, or 8 September 1805

33. Blodget, Economica; a Statistical Manual for the United States, 1806, pp. iii, 167

34. Natl Intelligencer ad 23 April 1806

35. WT to Madison 6 August 1806,

36. Madison to Jefferson 15 August 1806 ; Jefferson to Madison, 28 August 1806,

37. Latrobe to members of congress, 28 November 1806.pp. 296ff

38. Washington Federalist, 20 April 1808; Latrobe vol. 2 pp 600ff

39. Latrobe to Lenthall, 28 March 1804, letters p. 463

40. quote in Gordon Brown, Incidental Architect, footnote 1, p. 67

41. AMT notebook June 24, 1813

42. Thornton' finances

43. Latrobe to Jefferson, 12 July 1815 ;

44. Latrobe to Madison, 24, April 1816

45. Richard Brand Lee to Madison 27 April 1816; Lane to Madison 29 August 1816; 22 August 1816

46. Carter, Edward C,, Benjamin Henry Latrobe: Growth and Development of Washington. RCHS vot 71/72, p 142.

47. Bulfinch Life and Letters p. 215; Latrobe, Vindication, 1819

48. Jefferson to Latrobe, 9 May 1817,

49. LOC article on Thornton; WT to Jefferson, 27 May 1817; Thornton's drawing at "Enclosure... 27 May 1797." For Latrobe's suggestions see Latrobe to Jefferson, 24 July 1817

50. WT to Jefferson, 9 January 1821; Jefferson to Latrobe, 19 May 1818

51. Bryan, History of National Capital volume one,

pp. 317-8; Hunsberger, The Architecture of George Hadfield, p. 61; King, Julia, Hadfield, p. 95 ; GW to Commrs. 20 February 1797,

52. TJ to Cosway 2 October 1822

Comments

Post a Comment